This article was originally published on The Huffington Post:

Hi, Governor Jindal. You’re someone I looked up to when I was growing up.

Why? Because I grew up in a small Louisiana town as an Indian-American. I had no Indian community when I grew up, and I didn’t have an Indian household. What I did have was an interest in politics. As I found myself pondering over questions about society and government, I was pleased to see that an Indian-American paved the way in my state.

However, I learned from a young age that it was not acceptable to be Indian-American in Louisiana. Look around your state. The Indian-Americans who live here largely stay among their families and Indian communities. I never had that luxury. I wanted to fit in. Like most minority kids in majority white settings, I wasn’t completely sure what I was giving up. I gave up a lot that I hardly even had. Being an Indian-American in Louisiana contributed to a childhood feeling like I never really belonged here like my friends did.

But you seem to disagree.

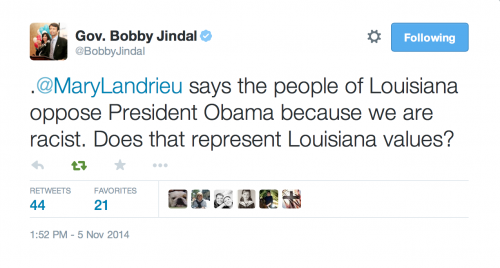

For you to say that our state is not steeped in racism is not just wrong; it’s delusional. Louisiana has been built off of African slave labor. The wealth disparity in this state leaves wealth in the hands of a few privileged, mostly white families. The entire structure of our state and our economy is created from racist structures.

Now the race dichotomy in Louisiana is black and white. Maybe because I’m mixed; maybe because I’m half-white; maybe because most people don’t know where India is: in any case, I didn’t fit well into it. I heard a lot of racism against black people, and I had to ask myself “Do people think this about me too?”

I can’t answer that question, but I can say that I was othered, and that I quickly understood that being Indian wouldn’t help me in being accepted by people.

The story may have been different for us if we grew up in the U.K. or a former British colony. The racism against South Asians is entrenched in societal structures.

Trinidad has an Indian prime minister with my own last name, but that doesn’t erase the fact that Indians were brought there as indentured servants. We were seen as and treated as lesser, and the discrimination doesn’t go that far back. How am I supposed to feel welcome on a campus that saw the death of two Indian students in 2007? Was it “Louisiana values” that allowed the suspects to walk away?

People in this state are racist toward President Barack Obama, and that is why people didn’t like him. Why else would a white man offhandedly tell me not to “vote for that n*****” in 2012? And in case you don’t remember, people were also racist against you, too. I know because they were racist toward me because of it.

Considering your statement, it’s ironic that a teacher at my Catholic school asked me if I voted for you in passing. I was puzzled by his question: I was in junior high; I couldn’t vote. The uneasy correlation hung in my mind: why would he ask my brother and I if we voted for you? I’ll answer that for you: it’s because my siblings and I were the only Indians at that school.

It’s the same reason that at an Ihop meal with my dad during your first campaign, some white kids at a nearby table hurled spitballs at me and made comments about my race. My dad was furious speaking to management, pledging to never eat there again. I didn’t understand what happened until he brought it up years later. This was a decade ago, but not much has changed.

So what? Can I be Indian, or do I have to downplay my identity to live in Louisiana? Can I have an Indian wedding if I marry a white Louisianan? Can I teach my children Hindi? Can I practice Hinduism? Can I do these things and be elected to public office, be a person that people can relate to? To answer that question, tell me–could you?

Louisiana is my home, and I can’t forget the kindness of people who made me feel welcome here. I have seen the good of people in this state. I know not everyone is a hardened or even intentional racist. But people carry racist prejudices based on their limited experience and empathy. I grew up in Opelousas, and it’s still socially and structurally segregated. I grew up hearing awful, inhumane assumptions and jokes about black people. Maybe that didn’t happen in your household, but white people said things in front of me because I’m not black. But I’m not white, either.

Now I know people of color who get to elected office experience a lot of pressure to stick to their roots. I know you weren’t elected as an Ambassador of Indian Culture. But in your statements, you don’t share your Indian experience. You downplay your identity, just as I did for so many years. I know it’s hard to be Indian in Louisiana, but it’s even harder for me to look at a governor who has yet to pave the way.

You can’t change what you are, Governor Jindal. I can’t either. We must embrace our identities rather than asking people to look past them. If you ask people to respect–not merely accept–your Indian identity, perhaps we can build toward a Louisiana that isn’t built off of racial prejudice.

Respectfully Yours,

An Indian-Louisianan

(I embrace the hyphens as well)

[divider]

Born and raised in Louisiana, Aryanna Prasad is attending Louisiana State University in Baton Rouge as a Political Communications and International Studies major (and currently suffering a mid-college crisis). The goal is to become an international journalist, writing about culture and politics or a domestic journalist writing about international affairs. At first glance, she may look different from many other brown girls because she is half-Irish American. Her parents are divorced and she grew up in a small Louisiana town without an Indian community. Since she was young, she knew she wanted to learn more about her culture, but she didn’t know how. She’s spent the past few years learning about her heritage through family, and watched many YouTube tutorials on how to wear a sari. From Twitter communities to collegiate ones, she’s learned a lot about what it means to be Indian, and she realizes now more than ever that she has the power to define this for herself. When she is not ranting about politics or consuming Atlantic articles, she enjoys traveling, jamming to hip-hop and seeking adventure.

Born and raised in Louisiana, Aryanna Prasad is attending Louisiana State University in Baton Rouge as a Political Communications and International Studies major (and currently suffering a mid-college crisis). The goal is to become an international journalist, writing about culture and politics or a domestic journalist writing about international affairs. At first glance, she may look different from many other brown girls because she is half-Irish American. Her parents are divorced and she grew up in a small Louisiana town without an Indian community. Since she was young, she knew she wanted to learn more about her culture, but she didn’t know how. She’s spent the past few years learning about her heritage through family, and watched many YouTube tutorials on how to wear a sari. From Twitter communities to collegiate ones, she’s learned a lot about what it means to be Indian, and she realizes now more than ever that she has the power to define this for herself. When she is not ranting about politics or consuming Atlantic articles, she enjoys traveling, jamming to hip-hop and seeking adventure.