by Mariya Taher

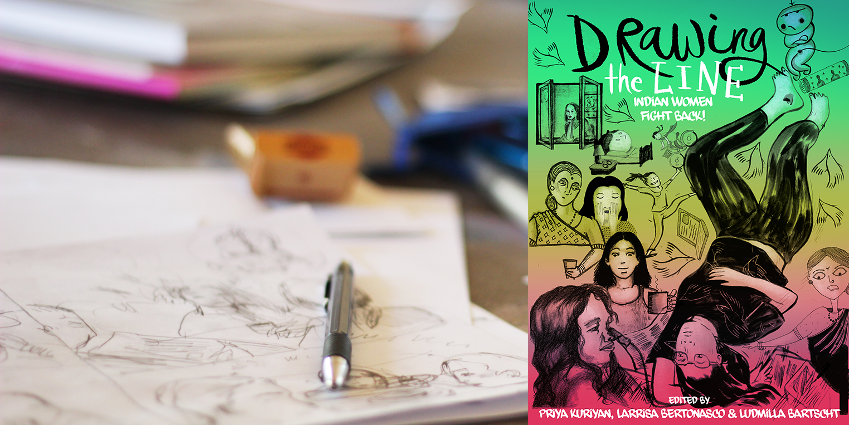

In a world where graphic novel artists are predominately men, Toronto-based comics publisher Ad Astra Comix, in partnership with Zubaan Books, are set to release the North American edition of “Drawing the Line: Indian Women Fight Back.”

This graphic novel comprised of 14 accounts turned into chapters of lived experiences by women in India, cover topics ranging from gender, sexuality, harassment, coming of age, family, sisterhood, racism, classism, and political struggle.

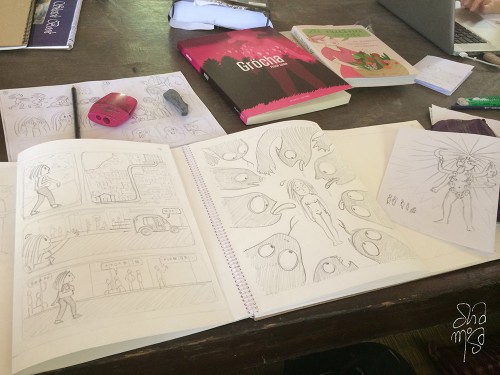

Using the medium of black and white comic books, “Drawing the Line: Indian Women Fight Back” allows audiences of every kind to visually step into each women’s experience, and artfully understand the notions and emotions of each author/artist.

One woman, Bhavana Singh, created an illuminating comic, “Inner Beauty and Melanin” which personifies melanin into a character, who in turn masterfully conveys “skintersting facts” regarding the large scale market of skin-whitening products found in India and the notion of shadeism—discrimination between lighter skin and darker skin members of the same community.

The character Melanin is able to takes these ideas and express how the shade of your skin plays into self-image and self worth of Indian women—both in India and abroad.

I can’t tell you how many times it was drilled into my mind growing up that fairer equaled lovelier, and how much I hated California Summers because of the sun and my darkening pigment—being a Californian who didn’t sunbathe was such an oddity amongst my white friends.

In Reshu Singh’s story, “The Photo,” in which her character, Bena has come of marriageable age and is faced with learning how to deal everyone’s expectation of who she should become—a married Indian woman—with the fear of losing her own true self and identity.

Bena is thoughtful and insightful, examining everyone around her, including her mother, who Bena says is their family’s “superhero.” The character notes that her mother had ambitions before getting married—she received her Masters in Economics and painted landscapes—but after marriage and children she stopped these pursuits to take care of her family. Bena then asks the simple, yet profound question, “Isn’t being happy heroic too?”

This portrayal of sacrifice makes the audience stop and wonder if the questions of “should or shouldn’t I get married” be replaced with “will it make me happy and will I still have my own identity if I do so,” instead.

There are many other chapters in the book which both overtly and covertly share experiences felt by thousands of women worldwide—we see many universal themes and struggles that women encounter on a daily basis.

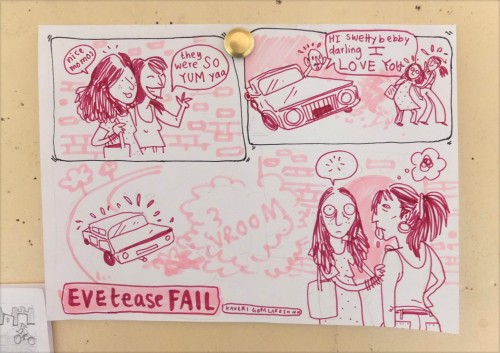

Kaveri Gopalakrishnan and Samidha Gunjal both address street harassment (eve-teasing). After reading these works, I immediately thought of my experience teaching an undergraduate course at San Francisco State University on gender, sexism, and social welfare institutions. During that experience, my students repeatedly brought up the topic of street harassment, how they walked faster at night when they were by themselves, how they were tired of men trying to hit on them or ogle their bodies and tell them to smile, and if they didn’t respond to these catcalls they were then promptly called a bitch.

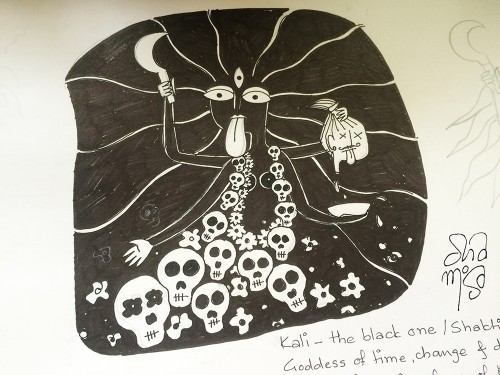

This innovative graphic novel helps to facilitate many necessary conversations—around race, shade, gender, employment, education, etc. It pushes the boundaries on what is considered “acceptable” by mainstream society—including drawing nude women and women speaking their minds about topics traditionally considered taboo.

Soumya Menon does a great job in “An Ideal Girl” of breaking age-old stereotypes held of Indian women. And that is exactly what the editors of this book were hoping to do, as explained by editor Larissa Bertonasco in the afterword:

“It was important to not only to broach the issue of violence against women and to reject the narrow view of women as victims, but also to develop a positive and bold outlook.”

The book is a first step, an experiment, a needed conversation starter because dialogue is what allows for change and without women sharing their stories with one another, nothing can change.

As editor Priya Kuriyan writes, also found in the afterword:

“We all have stories to tell and the difference is really between thinking about it and getting down to actually doing it. In a world that is dominated by stories that are told from the male perspective, I am so thankful for opportunities like this that help young women storytellers bloom.”

If “Drawing the Line: Indian Women Fight Back” appeals to you help them in their endeavor to create change through art by donating to their Kickstarter campaign.

Mariya Taher is currently pursuing an MFA in Creative Writing at Lesley University, MA. She received her Masters in Social Work from San Francisco State University and her BA from the University of California Santa Barbara, where she majored in Religious Studies and double minored in Global, Peace, and Security & Sociocultural Linguistics. Prior to attending Lesley University, she worked in the gender violence field for seven years. She has contributed articles to Solstice Literary Magazine, Global Voices, The Express Tribune, The San Francisco Examiner, BayWoof, and the Imagining Equality Project put together by the Global Fund for Women and the International Museum of Women.