I come from a culture that was born from years of “appropriation” as it would be termed today. The way I understand my existence encapsulates so many pockets of the world because the Caribbean is infused with traditions, big and small, from around the globe.

The women of my parents’ country sport both sarees and sundresses. The average Caribbean menu features both dhal and chow mein, both curries and fried rice. (Have you ever had West Indian Chinese food? It’s the food of the gods!)

Our most popular music is a fusion of the musical traditions of Africa and the global south. When I pray, I speak Arabic—a language to which I have no linguistic ties. Decades of historical cultural exchange and appropriation, resulting in a vibrant and newly forged cultural tradition.

So you see, it’s a bit difficult for me to subscribe to an outright rejectionist outlook with respect to cultural appropriation. Knowing the beginnings of my unique heritage has also allowed me to understand two crucial things that many appropriation policers fail to recognize:

1. Many elements of culture and religion do not belong to any one group exclusively, and

2. There is a real difference between appropriation and appreciation.

Last month my timeline and Twitter feed hummed with life; everyone was upset about the appropriation of Indian culture in Coldplay and Beyoncé’s “Hymn for the Weekend” music video. This much will be conceded: the use of South Asian poverty as a creative playground was problematic. I cringed as I watched slum children being used as props for the sake of an exotic video. But when I turned my attention to the accusations of appropriation that were thrown at Beyoncé, I became perplexed. She wore elaborate head jewelry and her hands were painted with henna. It became clear in that moment that, in outcries of appropriation, many people claim things over which they really have no monopoly. To illustrate this, it may be surprising to find that two of the most hotly contested forms of ornamentation—bindis and henna—are not exclusive (at all) to South Asian culture.

The Bindi. The mother of all cultural appropriation accusations.

In Hinduism, the bindi is a sacred marking indicative of the point of creation, while in other religious or cultural traditions it is also a representation of the third eye.

Similar forehead markings, however, are ever prominent in Egypt and along the Swahili Coast—a region that is rich with South Asian, Middle Eastern, and Persian influences. While, in some forms, Egyptian and Swahili forehead markings are strikingly similar to the South Asian bindi, in other forms—like tribal markings—these cultures possess a unique manifestation of a custom that many South Asians seem to think belongs to them exclusively. As conceded above, the Swahili Coast inherited the bindi after contact with South Asia through centuries of trade. However, they’ve done just that: they’ve inherited it. And, after hundreds of years, it firmly belongs to their cultural fabric as much as it belongs to the global south, no matter how it was conceived.

Henna. The henna plant is native to both northern and eastern Africa, as well as western and southern Asia.

Accordingly, its cosmetic use for skin and hair is prominent in the cultures corresponding with these territories. The use of henna as body art dates back centuries, primarily in Ancient India, but also in the Middle East and throughout North and East Africa. In fact, just as it is common to see a South Asian woman adorned with intricate henna designs climbing to her elbows, Kenyan and Somalian women, for example, also take pride in their own indigenous tradition of henna body art during wedding celebrations and religious holidays.

In sum, African (including African American) women and Middle Eastern women have as much right to henna as any South Asian woman. They cannot appropriate what already belongs to them.

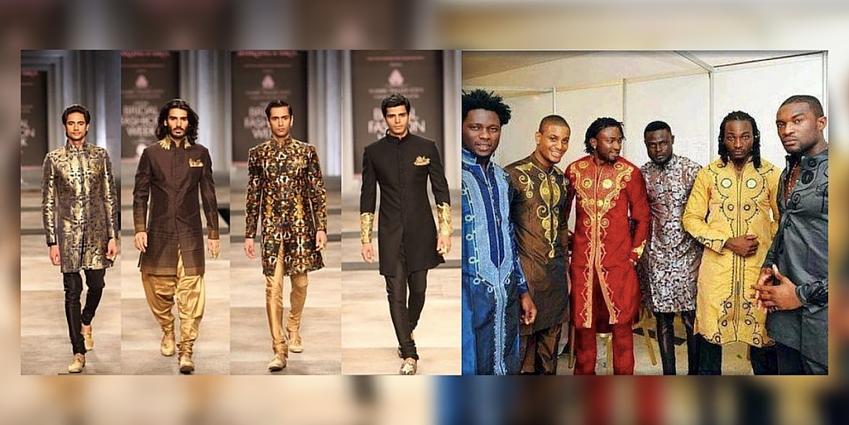

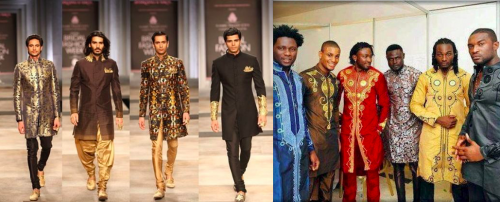

And the similarities and shared cultural elements become even clearer if we care to search and to learn.

The lines are, thus, far from clear, as the world overlaps in ways that many people, including myself, are yet to understand. How can we #ReclaimTheBindi when we have no exclusive right to it? How can we accuse Beyoncé of being culturally insensitive when African women have, for centuries, been painting themselves with henna and decorating their foreheads with tribal markings? How can we write think-piece after think-piece about the problematic application of henna, when the plant springs from the ground in so many corners of the planet where women have similarly thought, “You know, I bet if we decorated our hands with this, it would be pretty fly!”

Even in instances of true exclusivity, where does the element of cultural appreciation come into play? Does it come in at all? Does enjoying the elements of another culture necessarily have to incite offense at first blush before we can deconstruct the scienter of the actor? In an interview with Billboard, Priyanka Chopra discussed how she felt about bindis (again, can’t stress the lack of monopoly here enough) being worn by musicians. Her response?

“In today’s day and age, the bindi is not restricted to religious or traditional purposes, but is actually a very popular fashion accessory.”

Now, just because Chopra said it, surely, does not serve as some sort of exposition of the ideological footing to which we should subscribe. In fact, it would remiss to say that rejectionists should be dismissed altogether. Nonetheless, much more nuance needs to be added to the prevailing discourse on cultural appropriation aside from the purely rejectionist outlooks that currently reign. In having these tough discussions, both sides of the ideological spectrum must be willing to engage with topics that are sensitive and polarizing. It demands the tenderness that is requisite for the tremendous endeavor of dissecting identity and integrity.

This is not to say that there aren’t objectively problematic examples of appropriation. In media and the visual arts in general, this issue takes on other layers that easily go beyond the ideals expressed above. When institutions that purposely exclude people of color later go on to profit from the commodification of the cultures of the very people they exclude, that is a clear and unobjectionable problem. Just last month the New York Times spoke to 27 actors and actresses, including Mindy Kaling, regarding their experiences with diversity, or lack thereof, in Hollywood. Many of the stories were painfully similar, with common motifs of rejection and perseverance.

In a similar exposition, Aziz Ansari, in Season 1 Episode 4 (“Indians on TV”) of his show “Master of None,” aptly illustrated just how exclusionary Hollywood has been and continues to be, for South Asian actors specifically. In fact, the scarce roles that are available (unless you do like Kaling and Ansari and write roles for yourself!) are those that perpetuate the same tired stereotypes over and over again.

From casting Indians with accents as comedic relief to unapologetic uses of brown face, it is no secret, at least not anymore, that the visual arts are one of the many mediums through which a longstanding tradition of racist supremacy in America is reinforced. And when that is the case, it is hard to argue that it should be okay for those same institutions to utilize and profit from the very cultures they exclude as props for their creative endeavors.

Nonetheless, in the same breath that we condemn these institutions for their misuse and trivialization of traditions that do not belong to them, we must also acknowledge that Bollywood, the largest film industry in the world, is also egregiously guilty of the same charges. You need not search too far into the decades of the Hindi film archives before finding other cultures being used as props in addition to outright displays of orientalism and black face. While condemning institutions that exclude and subsequently degrade us, we must also condemn our own harmful institutions, which similarly espouse offensive mischaracterizations and trivializations of traditions that are not our own.

You see, the discussion surrounding appropriation takes on so many more layers than most think-piece authors care to engage with—layers that desperately need to be brought into the discussion. In the spirit of emulating a counter-rejectionist outlook (which almost never prescribes feasible alternatives), here is an attempt for prescriptive solutions for the intellectual gap in our discourse.

A pivotal point for advancing this discussion is learning where the line is, and what it looks like, between cultural appropriation and cultural appreciation. How do we engage with this? What questions should we be asking? We can start by engaging in a simple inquiry before resorting to rejectionist accusations of severe social misconduct.

1. Is the cultural element that is being used exclusive to my own cultural tradition?

2. Is the institution using this element a truly problematic one that is harmful to my culture’s dignity?

3. Based on the answers gleaned from 1 and 2, is this appropriation or appreciation?

Elizabeth Jaikaran is a freelance writer based in New York. She graduated from The City College of New York with her B.A. in 2012, and from New York University School of Law in 2016. She is interested in theories of gender politics and enjoys exploring the intersection of international law and social consciousness. When she’s not writing, she enjoys celebrating all of life’s small joys with her friends and binge watching juicy serial dramas with her husband. Her first book, “Trauma” will be published by Shanti Arts in 2017.

Elizabeth Jaikaran is a freelance writer based in New York. She graduated from The City College of New York with her B.A. in 2012, and from New York University School of Law in 2016. She is interested in theories of gender politics and enjoys exploring the intersection of international law and social consciousness. When she’s not writing, she enjoys celebrating all of life’s small joys with her friends and binge watching juicy serial dramas with her husband. Her first book, “Trauma” will be published by Shanti Arts in 2017.