I have a theory: a household functions best with no more than two adults. Two decision-makers can find the midpoint, and compromise between their preferences: debating whether to buy a BMW or a Hyundai? Find a car in mid-range price. Deciding what’s for dinner tonight? One person picks today, the other picks tomorrow.

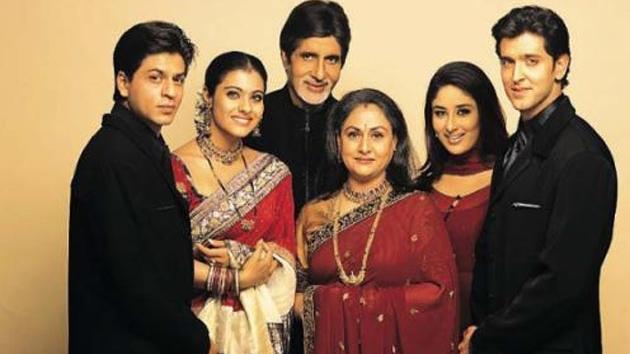

But this model gets challenging when there are more than two adults in a household. Teenage children spark arguments for this very reason because they feel they ought to be treated as adults and be allowed to weigh in on decisions. And the Indian paradigm of bringing aging parents under the same roof undoubtedly creates household tension by bringing a third, or maybe even fourth, point of view making it so no compromise can leave all parties happy.

Every Indian channel has multiple TV serials featuring similar problems in joint family households. While questionably entertaining, there is some truth to it. The Economist even ran an article chronicling power plays by mothers and daughters-in-law living under one roof. And yet, from an early age, we learn that we have a lifelong duty to our parents, that dropping aging parents off in a nursing home is one of the worst sins we can commit. After the years that our parents spend wiping our bottoms, loving us when we’re at our worst, prioritizing us above everything—how can we not take care of our parents? And so we seem destined for a household full of arguments.

As an Indian-American living in the U.S., where live-in caretakers are expensive and the resources for taking care of the elderly lag far behind the medicine that extends their lifespans, I wonder what I will do as my parents grow older and slowly become unable to live alone and unassisted. And none of the options are particularly appealing:

Return to the motherland

Sometimes my parents talk about moving back to India. Their retirement savings would go a longer way and the cost of hiring household help or live-in caretakers is low. Maybe they would be comfortable in the country where they grew up. Or maybe they would hate that it is no longer the country they left behind decades ago. Either way, it breaks my heart.

I have been living on my own for more than a decade, but the thought of living more than a short plane ride away is difficult. The idea of having to deal with them aging, falling sick, needing me while in India is tough—not just because of the emotional trauma, but also because of the anxiety of juggling annual leave, my own future children’s needs, and purchasing expensive plane tickets to be able to see my parents at a moment’s notice.

ShantiNiketan

Sometimes my parents entertain the idea of investing in an Indian retirement community in the U.S. This could be the college dorm experience they never had—living among peers who enjoy the same activities and laugh at the same jokes, being semi-independent but free of household responsibilities like daily cooking and cleaning, and still being in driving distance of children and grandchildren.

But there are also several cons: expensive housing, inability to transfer property rights to children. Perhaps most unappealing of all—they would be a part of the claustrophobically closely-knit community and gossip that they escaped when they moved to the U.S. In some ways, moving to ShantiNiketan is just a more expensive version of moving back to India.

Shirking my duty

We’ve all seen it in Indian families, and frankly, it seems to be the norm among American families. The people who find excuses—perhaps their own health, marital issues, etc.—to not take in their parents or to dump the responsibility on their siblings.

Worse yet are the people who think that giving their aging parents money is the same as taking care of them. Putting parents in a nursing home in the U.S. is unconscionable. Most Indian parents are not used to living among Americans, eating non-Indian (and non-vegetarian) food, and would die believing their children did not love them.

It is a short-sighted strategy because what goes around comes around. A child who does not see his or her parents take care of their aging parents might follow the example and not take care of his or her own parents when the time comes. Even without the threat of karmic retribution, I couldn’t live with this option.

Living under the same roof

And so I come the full circle back to this option. My parents had an arranged marriage and both expected to play a role in caring for their aging parents. If I marry, it will be in a different era, to a person of a different background, and for different reasons. It won’t be because I have to get married but because I love someone and cherish our relationship.

To think that in-laws won’t add stress to such a marriage is naïve; it’s optimistic to think it won’t disrupt my own career. I’ve seen enough in my own family to know that these issues are real. The fact that aging parents and in-laws are now likely to live for the majority of a couples’ married life exacerbates the issue. My parents have spent almost all of their 37 years of marriage—and they are entering senior citizenship themselves now—living with my paternal grandmother. And despite all the flaws in this system, it is the most palatable option I see because I cannot imagine leaving my parents in their time of need after everything they’ve given me.

Seethal Kumar is a dancer, writer, traveler, aspiring polyglot, and most of all, a dreamer. After receiving degrees in economics and international relations from Northwestern University and Johns Hopkins SAIS, she found her home in Washington D.C., where she could use her skills to encourage better cross-cultural understanding in the policy world. Follow her blog, where she writes about feminism, race, and identity with a South Asian twist.

Seethal Kumar is a dancer, writer, traveler, aspiring polyglot, and most of all, a dreamer. After receiving degrees in economics and international relations from Northwestern University and Johns Hopkins SAIS, she found her home in Washington D.C., where she could use her skills to encourage better cross-cultural understanding in the policy world. Follow her blog, where she writes about feminism, race, and identity with a South Asian twist.