by Vijai Kumar – Follow @TheKumarEffect

The following post has been republished with permission from thekumareffect.wordpress.com.

I remember watching a Russell Peters interview when I was a kid. He talked about his upbringing in Brampton, Ontario, Canada, my birthplace. Peters, as an Anglo-Indian, spoke of his firmly ‘outsider’ perspective. This elucidation put into words the feelings I’ve had for years.

Throughout most of my own upbringing, I consistently felt that while I held membership to a larger community and demographics, the nuances of my identity forced me to acknowledge my unique differences. I find myself, in every concentric layer of my identity, positioned at the margins.

I am a second generation Canadian of Guyanese descent. My parents arrived in Toronto in the early 80s along with most of the Trudeau-era immigrants (there is a particular brand of reverence for Pierre Elliott Trudeau among West Indian communities). Guyanese diaspora is split between two areas: the Greater Toronto Area (GTA) and Jamaica, Queens, New York City.

Peters mentioned that in many ways, Canada is amalgamated with the USA to form a culturally monolithic North America. Being from Brampton, the city’s identity is inextricably tied to the metropolitan hub of Toronto, left to culturally develop in the shadows of an international city. There’s also the lack of inclusiveness for Brampton in the GTA, similar to the way an older sibling attempts to dissociate themselves from their younger brothers and sisters.

Don’t get me wrong, I have always felt included and respected growing up as a Guyanese in Brampton. All of the cultural sensibilities I hold dear to me — the music, food, movies, pop culture, even language — reinforced the sense of community I now associate with Brampton. I would be disingenuous, however, to say that I didn’t feel distinctly different from my larger community. This is the larger issue with our insistence of homogeneous groups communities — we expect them to be homogeneous.

The last concentric layer of Peters’ identity was the most interesting to me. As an Anglo-Indian, he felt uniquely distinct from the ‘Indian’ community under which he is generally classified. As a Brampton-born Canadian of Guyanese descent, having been immersed in desi-Canadian culture, my peculiarities have been perpetually reinforced.

[Read More: Brown Boy of the Month Viraj Sikand Explores his Kenyan, Korean, and Desi Heritage Through Environmentalism]

My parents, again like most immigrants, had a very difficult time in their early days in Canada. Multiculturalism as an ideology was in its infancy, cultural diversity was a foreign idea, and my parents were certainly no strangers to racism (and in particular my mother’s case, sexism). To make matters worse, their first home as newlyweds was in a pauperized area of Toronto called Driftwood.

I was not born during this time, but my parents recollect, with embarrassment I might add, the cockroaches of which they would catch a short glimpse every time they turned on the lights. When my father got up for work, he would walk by drug dealers and prostitutes as they conducted their respective businesses in the parking lot of his building. As my mother was pregnant with my sister at the time, both my parents understood this was no place to raise a family.

My parents moved to Brampton in the early 90s. This was a bustling suburb with potential. Land formerly used for agriculture was quickly built over with homes — very affordable homes. This is where I was born. Brampton quickly developed a sizable South Asian community. I went to high school with a multiplicity of cultures but became particularly familiar with Punjabi culture.

Most Guyanese engage with India through the prism of Bollywood. Amitabh Bachan and Shahrukh Khan are worshiped to the same degree of obsession in Guyana as they are in India. I engaged with the Indian component of my identity through a more unconventional means: music. I began learning tabla at the age of 12 and developed an early liking for Indian classical music.

When my roommate from university invited me to his wedding, I was caught off guard, considering it was in India. But nevertheless, I felt compelled to go. I didn’t plan for the trip, but I was overcome with how fortuitously the opportunity came together.

My family had embarked on a journey to India and Guyana in the late 90s to obtain archives of my ancestors in an attempt to trace my distant Indian relatives. My Nana (maternal grandfather) was successful in locating the exact village in India from where his father originated.

Kodwat is a small village in the state of Uttar Pradesh on the border of India and Nepal, near Gorakhpur (a metropolitan city). When my Nana first visited, he introduced himself as Gopi Chaudhury’s son (my great-grandfather’s son). The village was overwhelmed, to say the least. The only known family to have left to America (Amrika – term used to describe the entire western hemisphere), and for nearly 100 years, there was no word from him or his progeny. They assumed that Gopi Chaudhury’s branch on the family tree was defunct. This was an incredibly emotional time for everyone.

[Photo Courtesty of Vijai Kumar]

[Photo Courtesty of Vijai Kumar]

In 2015, when I made the trip to Mumbai, aside from feelings of apprehension embarking on my first trip outside of North America (even more intimidating was the fact that this was also the first trip I had made without my parents), I was generally made to feel at home by my roommate and his family. One morning, as I was sleeping off my jetlag, a relative of my roommate’s woke me up telling me that I had a guest. I was shocked at the idea that I had a guest in a country to which I have never been.

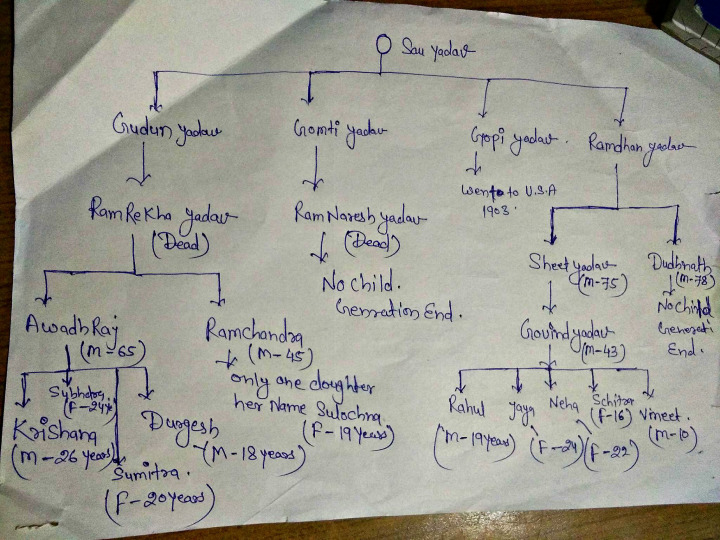

I got out of bed without freshening up, walked slowly into the hall, and saw Krishna Kumar Yadav (KKY), a very distant relative of mine. His great grandfather, Gudun Yadav, was brothers with my great grandfather, Gopi Yadav. As you can see in the illustration I included above, the record of my great grandfather ended when he left for “America” in 1903 (believed also to be 1907).

Our first encounter wasn’t as awkward or superfluously formal as I expected. We were both cordial and polite. He told me that he improved his English considerably since the last relative of mine came to visit. He’s been in remote contact with most of my family for a few years. He knew English quite well, so it was natural that he served as the conduit between families. I was the first person of his equivalent generation to meet him.

While drinking chai, KKY explained my family history to me, a coveted oral tradition among his family in Kodwat. We spoke about his life in India, working between Mumbai and Delhi, traveling a surplus of 50 hours on trains constricted by hazardous overpopulation. He spoke of the politics in the land, the countless times he was denied visas to travel west, caste discrimination, India’s relationship with Pakistan. He also spoke about the simple elegance of Kodwat, the opportunities he received to be educated and to move to Delhi for work, and the folk traditions that my great grandfather enjoyed.

He spoke excitedly about India, a land from which my family has been disconnected for about a century. Strangely, I listened with a distant feeling of nostalgia – a longing for a land I had never previously known. It was after that conversation that India captivated me. The connection had been formed.

[Photo Courtsey of Vijai Kumar]

[Photo Courtsey of Vijai Kumar]

KKY taught me the paradox of our desires. I can see the paradox in his own pecuniary ambitions. Moving him away to densely populated cities ironically resulted in a self-imposed sequestering from authentic human relationships, especially that of my family.

Indian culture is different than North American, however. Hospitality is presupposed but never demanded. The unforgiving streets offer a sophisticated philosophy of compassion. Love is presumed, whereas, in North America, a version of the opposite is presumed. India isn’t all rainbows, though.The conditions are much harsher than anything I’ve experienced in Canada, but the ‘love’ remains intact.

My cousin is inured to the pains of hardship but is vibrant with the love in his country. It’s an idiosyncrasy that is difficult to put into words, but it is with this ‘love’ my cousin endures.

Our last meeting was poetically in front of the gateway of India — built for the arrival of King George V and Queen Mary roughly three years after my great-grandfather left for Guyana. It was getting late and KKY offered his goodbye. Before he could go, I offered him recompense for all that he had sacrificed (including days at work) for my comfort. Before I could take the rupees out of my wallet, he gently placed his hand over it and refused, persistently, but elegantly. He said that he considered me as a family member; and that he has enough money.

[Photo Courtesty of Vijai Kumar]

[Photo Courtesty of Vijai Kumar]

I returned to Canada with a heightened awareness of my own country as well as my cultural sensibilities. My parents and sister insist on hearing my stories about India, and as much as I would like to limn every detail of my adventures, I encapsulate my sentiment saying “you must go and see for yourself.”

I speak with KKY regularly on Facebook. Recently his sister got married — as did my cousin. We exchange pictures and well wishes. It’s pleasant to be able to speak with my distant relative, to remind myself of my extended identity, but I also think it’s about time for him to discover the land to which Gopi Yadav traveled over a century ago.

Vijai Singh is a student at the University of Waterloo studying Political Science and Economics. Born in the Canadian city of Brampton, he enjoys getting involved in city-based cultural initiatives such as The Bramptonist and Brampton Says. He is fascinated by big existential questions, which is represented in much of his personal writings. As a pastime, Vijai enjoys playing the tabla, the popular drum of North India.

Vijai Singh is a student at the University of Waterloo studying Political Science and Economics. Born in the Canadian city of Brampton, he enjoys getting involved in city-based cultural initiatives such as The Bramptonist and Brampton Says. He is fascinated by big existential questions, which is represented in much of his personal writings. As a pastime, Vijai enjoys playing the tabla, the popular drum of North India.