by Mayura Iyer – Follow @tweetsbymayura

On Friday, January 29, President Donald Trump signed an executive order that indefinitely suspended the admission of Syrian refugees to the United States and limited the admission of other refugees, all while promising to prioritize Christian refugees. He also signed another executive order banning citizens of seven Muslim-majority countries from entering the U.S., including Iran, Iraq, and Syria. Many are calling these executive orders an evolution of his original campaign promise for a #MuslimBan, and are fearful that a Muslim registry will follow. In the wake of these executive orders, there have been protests, social media posts, fundraisers, and an outpouring of grassroots activism and allyship to support the Muslim-American community.

However, in the days that have followed, I’ve also seen a lot of comments about how Trump’s executive orders against Muslim countries and refugees are unprecedented, how it is “un-American” to turn against immigrants and refugees and to discriminate based on religion – and I disagree. Waves of nativism – waves of anti-immigrant sentiment and white Anglo-Saxon superiority – are not unprecedented. In fact, they are a common occurrence throughout U.S. history, and often resurge during times of economic downturn or war. Moreover, during these waves of nativism, we often see severe restrictions on immigration and targeted deportations on specific immigrant groups.

A History of Nativism in the United States

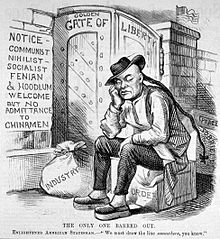

A political cartoon satirizing the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. [Photo Source/Wikipedia]

A political cartoon satirizing the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. [Photo Source/Wikipedia]

In 1882, the U.S. passed the Chinese Exclusion Act, which banned Chinese immigrants from entering the U.S. for 10 years. This was, in part, a reaction to nativist sentiments on the west coast, where Chinese immigrants had begun arriving in the 1860s to help construct the transcontinental railroad. Many Californians at the time felt that Chinese immigrants were taking their jobs and were at fault for declining wages and the economic problems that came with the Panic of 1873 and the 1882-1885 recession. This was followed in 1917 by the Asiatic Barred Zone Act, which restricted immigration from “undesirable” countries, particularly “those adjacent to the continent of Asia.” Unsurprisingly, the U.S. had just been through an economic panic in 1910 and a recession from 1913-1914.

In the midst of the “Roaring Twenties,” the economic boom in the U.S. following World War I, there was a large influx of immigrants. The Great War had wreaked havoc on Europe, and as a result many immigrants hoped to find a better life in America, which had survived World War I relatively unscathed. The sudden boom in immigration led to yet another wave of nativism and anti-immigrant sentiment, which led to the passage of the Johnson-Reed Act, or Immigration Act of 1924. This act established a national origins quota that severely limited immigration from Southern and Eastern Europe while also completely banning immigration from the continent of Asia (which includes the Middle East).

A photo from 1932 of Mexican Americans waiting to board trains in Los Angeles back to Mexico as part of the “Repatriation Movement” by the U.S. government. [Photo Source/Media.NPR.org]

A photo from 1932 of Mexican Americans waiting to board trains in Los Angeles back to Mexico as part of the “Repatriation Movement” by the U.S. government. [Photo Source/Media.NPR.org]

The persecution of immigrants continued after the Roaring Twenties when the stock market crashed in 1929. During the Great Depression, between one and two million Mexican nationals and American citizens of Mexican descent were deported because they were blamed for the failure of the economy. About 60 percent of those deported were believed to be American citizens. While there was no official deportation act, these deportations were carried out in waves throughout the 1930s as part of a “Repatriation Movement”, using the logic that doing so would create more jobs for “real Americans.”

Passengers onboard the S.S. St. Louis, many of whom were Jewish refugees, who were denied entry into the United States during World War II.[Photo Source/JDC Archives]

Passengers onboard the S.S. St. Louis, many of whom were Jewish refugees, who were denied entry into the United States during World War II.[Photo Source/JDC Archives]

The fear of refugees as a national security threat is also not without precedent. In the years leading up to World War II, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt argued that Jewish refugees fleeing the Holocaust and the Nazi regime may have Nazi spies amongst them. The U.S. infamously denied entry to Jewish refugees aboard the S.S. St. Louis in 1939, viewing them as a threat to security.

Additionally, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt saw Japanese Americans as a threat to national security in the wake of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941. He signed Executive Order 9066 in 1942 ordering the internment of all Japanese Americans in camps, where they lived in poor conditions as second-class citizens and were subjected to abuse by military guards. In 1944, the landmark case of Korematsu v. United States upheld the constitutionality of internment, asserting that concerns about national security outweighed the constitutional guarantee of equal rights. President Ronald Reagan reluctantly apologized for the internment of Japanese Americans in 1988 and gave each surviving internee $20,000. The Department of Justice also issued an admission of error for the decision in Korematsu v. United States in 2011 – however, the decision has never been officially overturned. While these acts were carried out in the name of protecting national security, only 10 Americans were convicted of spying for Japan during World War II – none of whom were of Japanese descent.

Bans on nationals from certain countries in the name of national security are also not unprecedented – during the 1979 Iranian Hostage Crisis, President Jimmy Carter cut diplomatic relations with Iran and banned Iranian nationals from entering the United States. A film by Iranian filmmaker Parviz Sayyad titled “Checkpoint” (1987) tells the story of a group of Iranian students who detained at the US-Canada border in April 1980 who were trying to return to the US to continue their education.

Finally, during his presidency, President Barack Obama deported over 2.5 million people – more than any other president. Even in recent history, following the Great Recession and with the rise and fear of Islamic terrorism, we’ve seen an increase in nativism and an increase in deportations.

This is not to equate Obama, Carter, Roosevelt, or any other president named to Trump. This is to say that Trump’s policies are not a unique occurrence or without precedence – they are a product of our nation’s long history of nativism, of turning against immigrants of all backgrounds. This incomplete list of legally sanctioned discrimination against immigrants doesn’t even encompass the other, unofficially sanctioned ways immigrants have been persecuted in the U.S., such as the hiring discrimination faced by Irish immigrants after the Potato Famine or the unsafe working conditions faced by Italian immigrants at the onset of the 20th century. When our economy is not doing well, we blame immigrants for “taking our jobs”. When we are at war, we see foreigners as a “threat to national security.” In short, when Americans are scared, the first people we turn against are often immigrants.

Perhaps if we view being “American” as an ideal, as a set of values to aspire to, then, yes, a #MuslimBan is un-American. However, if we view being “American” as a set of actions taken by our country and enabled by legislation, history has taught us that a #MuslimBan is, unfortunately, all-too-American. Instead of focusing on whether a #MuslimBan is what “America looks like” or what “is American”, we need to focus on a different question – what America can and should be. And we can and should be better.

Mayura Iyer is a high school teacher, advocate, and a writer who came to Dallas, Texas by way of Virginia and Washington, D.C. She received her B.A. in Foreign Affairs and her Master of Public Policy from the University of Virginia, and hopes to use her policy knowledge and love of writing to change the world. She is particularly interested in the dynamics of race in the Asian-American community, domestic violence, mental wellness, and education policy. Her caffeine-fueled pieces have also appeared in the Huffington Post, Literally, Darling, and Mic.com.

Mayura Iyer is a high school teacher, advocate, and a writer who came to Dallas, Texas by way of Virginia and Washington, D.C. She received her B.A. in Foreign Affairs and her Master of Public Policy from the University of Virginia, and hopes to use her policy knowledge and love of writing to change the world. She is particularly interested in the dynamics of race in the Asian-American community, domestic violence, mental wellness, and education policy. Her caffeine-fueled pieces have also appeared in the Huffington Post, Literally, Darling, and Mic.com.