by Priya Arora – Follow @ThePriyaArora

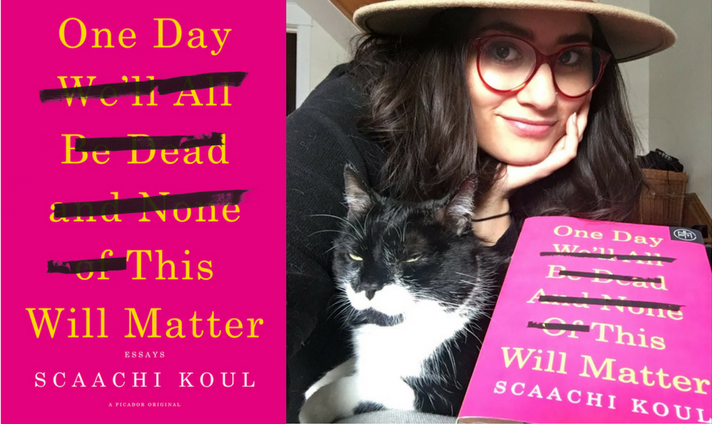

If you’re active on Twitter, chances are you’ve heard of Scaachi Koul—a senior writer at Buzzfeed, Koul’s sharp wit and humor are the edifices of her online presence. Koul’s debut book, “One Day We’ll All Be Dead And None Of This Will Matter,” is a collection of fiercely witty and deeply vulnerable essays about growing up the daughter of Indian immigrants in Western culture—and it’s a book almost any brown girl will be able to relate to.

Koul was raised in Canada, the daughter of Kashmiri parents who immigrated from India. In book’s the opening essay, “Inheritance Tax,” Koul talks about her fear of flying, tying it seamlessly to her parents’ story of marriage and moving to a new country.

“When I was thirteen, my mom asked me where I’d get the money to travel and I said, “From you, of course.” She laughed me straight out of her kitchen nook,” Koul writes.

The essay sets the tone for the book, with essays on a variety of topics that are bridged together by something I felt incredible resonance with throughout: the immigrant experience. Koul and I had a chance to chat recently, and I asked her about this theme that loomed large for me as a reader.

“I think a lot of the immigrant experience is ultimately about loneliness and loss,” Koul shared. “You sort of come to the States or Canada or wherever you go and it feels really lucky, like you have such fortune to be able to do that. But then you move and you feel this inescapable sense of loss because you can never get things back. And it doesn’t mean that you regret the decision or it was a bad one or your family won’t profit from it, but it creates this legacy of anxiety.

I don’t know if this is true for all immigrant families, but certainly for mine, we are predisposed to misery—so right out of the gate, we were going to be unhappy about something. Certainly, the immigrant experience influences the overarching themes of the book but a lot of is about that loss when you break connective tissue.”

This loneliness within immigration, Koul said, is a lot of why she felt she had to write a book like this.

“When you move or your family moves and you’re not a part of the majority, you end up feeling lonely. I certainly felt lonely when I was younger and I wish I had things like Brown Girl Magazine or my book to help that transition when you’re kind of confused about what your deal is and where you fit. It’s also nice to be able to own art. Brown people don’t have a great ciritical mass when it come st o music or movies outside of Bollywood. We don’t have a lot of north American things to attach to, but we do have some really good books. I thought it would be nice to be sort of like here, we can all own this.”

The book is immensely relatable, but what truly sets it apart is Koul’s witty take on everything from the serious to the lighthearted. In many essays, her heartfelt attachment to the experiences she’s had catches me off guard, which shows me the silencing of vulnerabilities that many of us as South Asians have been socialized to. Koul talks about body image, full of confessions and scenarios most brown girls have also faced, from finding the right size of clothing (or, in Koul’s case, facing the plight of a dressing room malfunction) to body hair and colorism. She also addresses harassment and rape culture, as well as post 9/11 racism. It’s all heavy (and sometimes sad) stuff, and yet, Koul’s insightful humor manages to toe the line of being real and vulnerable but also being able to laugh.

“A lot of people ask me, “when did you become funny?” and its like, I had to or else I would’ve killed myself,” Koul said. “You need something. I cant and won’t write an opus the misery of human existence as a brown person and not give you a joke at the end of it, because you’ll go insane.”

This is exactly what makes the book hit so close to home as a fellow brown woman.

In another essay, “Mute,” Koul opens up about Twitter backlash she faced non-white, non-male people to contribute to BuzzFeed. The kind of vitriol she faced even got picked up by the news and the whole ordeal pushed Koul out of the Twittersphere for a while. When I asked which of the essays was her favorite, Koul told me she wrote “Mute” in a blind rage.

I asked Koul how she built up the kind of thick skin she seems to have with internet trolls, and just people in general, without playing the victim about how hard it is to be a brown person.

“It’s not very effective. I just don’t know what anyone would get from that. Life is sad. Parts of it will be sad but I don’t get anything from that. There were protions of the book some that white angry people will view as victimizing and have and have told me as much that’s a misinterpretation of reality.

I cant listen to a lot of it because it doesn’t mean anything. The context with which you come to the book is relevant. Of course, as a brown woman, you can relate to it. But for others, I think you can read it and still like it, even if you’re not brown. However, I don’t need to cater everything to [those people]. So if you come to it and don’t like it, that’s unfortunate but not everything is for you.”

Koul’s parents, of course, have a visceral presence in the book. With everything from frenzied calls to bouts of silence, their mixture of obligation and love and guilt blend into a parental cocktail that feels immensely familiar for South Asians. Beyond stories about them, emails from Koul’s dad cushion the introduction to each new essay, giving the reader an intimate glimpse into their relationship. He even read his own emails for the audiobook.

I asked Koul how her family has reacted to the book:

“I know some of my extended families have bought it but no one has said anything to me which is correct. My mom read it and did her whole fainting couch routine but now she’s fine, which is exactly what I thought would happen. My dad hasn’t read it and he won’t because he knows better. My mother said to him, ‘you can’t read this and get upset because it’s not for you.’ And it’s not for him; it’s not.

His whole thing is he just wants to know how many have sold. I’ll call him and he’ll pick up and just say ‘What’s the number like a psychopath. He wants to be part of the publicity team, which, quite frankly, he’s doing a great job.”

So what does Koul hope readers will take away from the book?

“I hope it makes you call your dad more often,” she said.

And her advice to young brown girls who grapple with the same issues she illuminates in the book, is of course, to read the book. But there’s also more.

“I think feeling amiss makes you strong later but its hard to sort of see that when its happening. I spent a lot of my younger years trying to fit by carving myself into shapes that weren’t gonna happen. I would hope someone younger than me doesn’t do that because its going ot make you miserable. And nothing bad happens to you if you don’t fit in in those ways.”

Also, in a very Scaachi-esque bit of final advice, “get a sense of humor because you won’t make it otherwise.”

“One Day We’ll All Be Dead and None of This Will Matter” is out now in the U.S.

Priya Arora is a queer-identified community activist, editor, writer and Netflix enthusiast. Born and raised in California, Priya has found a home in New York City, where she currently works as a Web Editor at Hearst Business Media. When she’s not working, Priya enjoys watching old school Bollywood movies, laboring over NYTimes crossword puzzles, reading books she never finishes, and eating way too much of her partner’s homemade Hyderabadi biryani.

Priya Arora is a queer-identified community activist, editor, writer and Netflix enthusiast. Born and raised in California, Priya has found a home in New York City, where she currently works as a Web Editor at Hearst Business Media. When she’s not working, Priya enjoys watching old school Bollywood movies, laboring over NYTimes crossword puzzles, reading books she never finishes, and eating way too much of her partner’s homemade Hyderabadi biryani.