by Shruti Rajan – Follow @browngirlmag

My day starts with a 25-minute walk to the Keystone Foundation campus. By now, I can comfortably navigate the curves and settle in to enjoy the treasures that the walk offers. The junction store with the annas slurping chai cues that the city is waking up. The abandoned house in the valley reminds me that I’m halfway to the campus. Right before I reach Keystone, I can expect the smell of the fresh cover of dew lifting from the town. I look forward to the comfort that my walk to work brings every morning.

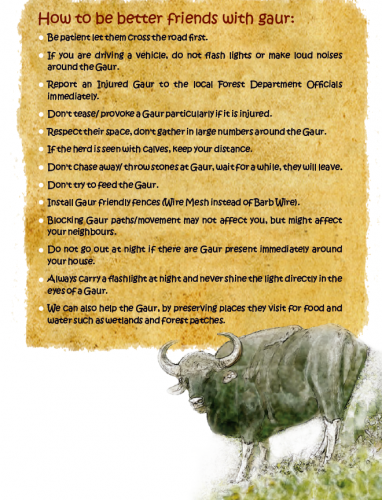

Moreover, the predictability of my surroundings has allowed me to deepen my interactions and ponderings about the environment that I walk through. However, the one thing I cannot predict about my environment is whether I’ll come across the wildlife that the surrounding forests let wander in (anything from the Indian gaur to elephants). Although we try our best to avoid one another, we share the road for our means. I use it to get to work and the animals use it to get from one agricultural snack to another.

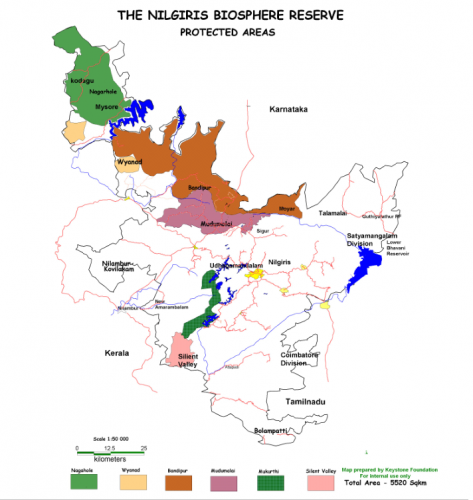

Before we go on, a little (okay actually a long) interlude to explain why I am giving you a detailed account of my morning walk. You see, living in the Nilgiris has increased my engagement with the natural world. Conversations with my colleagues, a majority of whom are environmentalists and ecologists, have increased my fascination for human-wildlife interactions. Especially when this interaction — inadvertently shaped through political change — influences health outcomes. My exploration of the ‘wild’ in the Nilgiris has led to a realization that as the development and policies surrounding the forests in Tamil Nadu and all around India get fast-tracked, the delicate balance of man and wild tilts even further.

Field visits to places like Masinagudi Adivasi colony, a village that has been relocated to the fringes of the Mudumalai Tiger Reserve, has allowed me learn more about the restrictions imposed by the Tamil Nadu forest department. In efforts to “relieve the pressures that the indigenous peoples put on the forest,” the state relocated the villagers back in 2006 and still to this day restricts their use of and collection of food, resources, and prodder from the forest [2]. The idea that conservation is being hindered by human activity inside the forest has been long held and long contested. In fact, many researchers have pointed out that the villagers’ co-existence with the wildlife population for thousands of years has helped manage, protect, and shape conservation efforts.

The villagers are often times the ones that report poachers and illegal activity that occurs in the forests [2, 3]. They are also the ones that have the best knowledge and motivation to protect their land. More importantly, the relocations also bring up the question of why the forest department actions are contradictory to the Forest Rights Act (FRA) that was passed in 2006. The rights conferred under the FRA allows individuals to “manage and conserve the part of the forest that falls within the traditional boundaries of their village, and the right to use and sell minor forest produce like tendu (a leaf used to make beedis), bamboo, honey and medicinal plants [1].” However, as seen with the Masinagudi Adivasi colony, the distribution of these rights are not always implemented fairly or in a timely manner.

Although the designation of protected areas, such as the Mudumalai Tiger Reserve, might be done on the premise of conserving biodiversity, it strains the balance between the community members and the wildlife sharing the forest. It also increases and intensifies the animosity between the state (who is treating to enforce the policies set out by the forest department) and the people (who are getting pushed out of their land and being told that their usage of the forest is illegal).

It is shocking that despite information on how tribal people play a crucial role in conservation, the rights of the Adivasis are still neglected in this manner. Land rights might seem very far off base from my work on the community health and well-being team at Keystone, but it can’t be denied that when addressing issues of tenure security and access rights of forest communities, there is a shift towards a community conservation regime that is more food security and well-being oriented [3]. FRA titles have the potential to recognize and preserve community knowledge that have contributed naturally to the conservation of forests and biodiversity. Moreover, there have been many accounts that have shown how the empowerment of the local community institutions and increased recognition of rights have enabled communities to better deal with external threats to community resources and community health [5].

So, now back to our wild animal friends. The gaurs, tigers, and elephants (oh my!) that I often have to keep an lookout for on my morning walk. These creatures have always a part of the Kotagiri landscape but their presence has just become more notable because of the increase in human movement and development in the town. They wander in from the surrounding forests in search of food. These instances are bound to happen more often since the forest cover and landscape for their resources are dwindling. Because of their persistent appearances, the town inhabitants have gradually learned to adapt to the sight of the ‘wild’ in their backyards.

Quick side-note: Keystone has recently started using an app in efforts to manage the human-wildlife conflicts as a community and for pre-empting conflicts. This app, which has simple entries such as location, time of spotting, date, sex, age and other observations if any, can create a volunteer base of students and citizens to assist the Forest Department. Read more about it here.

Even though state officials try to section off a land, try to make it into reserves or say that it’s sanctioned off as forest land, continued encounters with wildlife, even in a developed town, highlights that humans are also a part of nature. I think it’s important to remember that animals can drift outside the artificial boundaries of the ‘wild’ just as much as the people, who have no alternative source of food, fuel, or prodder, cross into the same boundaries in search of their resources. Especially if these resources and landscape is what they use to deepen their own interactions with their environment. In fact, to the indigenous communities, the forest has been a place of worship, their only source of income, and the place where they create their routines (such as my walk) and rituals for centuries now.

Keeping this in mind, it is crucial to push for conservation policies that advantages both the indigenous populations and the animals. Keystone is currently taking this angle on conservation by informing the indigenous communities about their FRA rights and helping them secure land titles. The staff part of the community health and well-being team recognizes this as the phase one of our overall health project. Only when we protect tribal peoples’ rights to their lands, listen to them, and support them can we move towards a space to prioritize health and well-being.

I leave you with an excerpt from a poem by Gregory Bahla, a land rights activist. It was taken from This is Our Homeland: A Collection of Essays on the Betrayal of Adivasi Rights in India, 2007.

We dream of our land.

Everything that we see, we walk on,

we feel through our body,

belongs to our land.

We need the land to think about ourselves,

to know who we are.

We are no people without our land.

The government should understand this.

This is not negotiable.

Land cannot be compensated.

_________

[1] ActionAid (2013). ‘Our Forest Our Rights. Implementation Status of Forest Rights Act—2006. Natural Resources’. Knowledge Activist Hub. New Delhi: ActionAid.

[2] Baviskar, A. (1994). ‘Fate of the Forest. Conservation and Tribal Rights’, Economic and Political Weekly 29 (38): 2493–501. Google Scholar.

[3] Equitable Tourism Options (EQUATIONS). This is Our Homeland: A Collection of Essays on the Betrayal of Adivasi Rights in India. Equations, 2007.

[4] Rangarajan, M., & Shahabuddin, G. (2006). ‘Displacement and relocation from protected areas: Towards a biological and historical synthesis’. Conservation and Society 4 (3), 359.

[5] Sharma, M. (2012). ‘Dalits and Indian Environmental Politics’. Economic and Political Weekly 47 (23), 46-52.

A previous version of this article was originally published on 1/16/2018 on American India Foundation. AIF’s William J. Clinton Fellowship for Service in India builds the next generation of leaders committed to lasting change for underprivileged communities across India, while strengthening the civil sector.

Shruti is eager to use the skills she gained to keep building a foundation of meaningful engagement with the country of her birth. Her interest in the health and wellness of marginalized populations developed while volunteering at a village hospital in an Indian village. Since then, Shruti has deepened her experience in instigating community-oriented health initiatives by working as the outreach and health education coordinator at a mental advocacy. She also worked as an honorary research associate at a radiology stroke lab following graduation. She came to the AIF Fellowship from Madison, Wisconsin, with a Bachelor of Science degree in Neurobiology and Psychology.

Shruti is eager to use the skills she gained to keep building a foundation of meaningful engagement with the country of her birth. Her interest in the health and wellness of marginalized populations developed while volunteering at a village hospital in an Indian village. Since then, Shruti has deepened her experience in instigating community-oriented health initiatives by working as the outreach and health education coordinator at a mental advocacy. She also worked as an honorary research associate at a radiology stroke lab following graduation. She came to the AIF Fellowship from Madison, Wisconsin, with a Bachelor of Science degree in Neurobiology and Psychology.