As people around the world ushered in the Year of the Ox, celebrations of the Lunar New Year in America have been muted as the Asian American community is still reeling in the wake of multiple incidents of violence and harassment over the past few weeks.

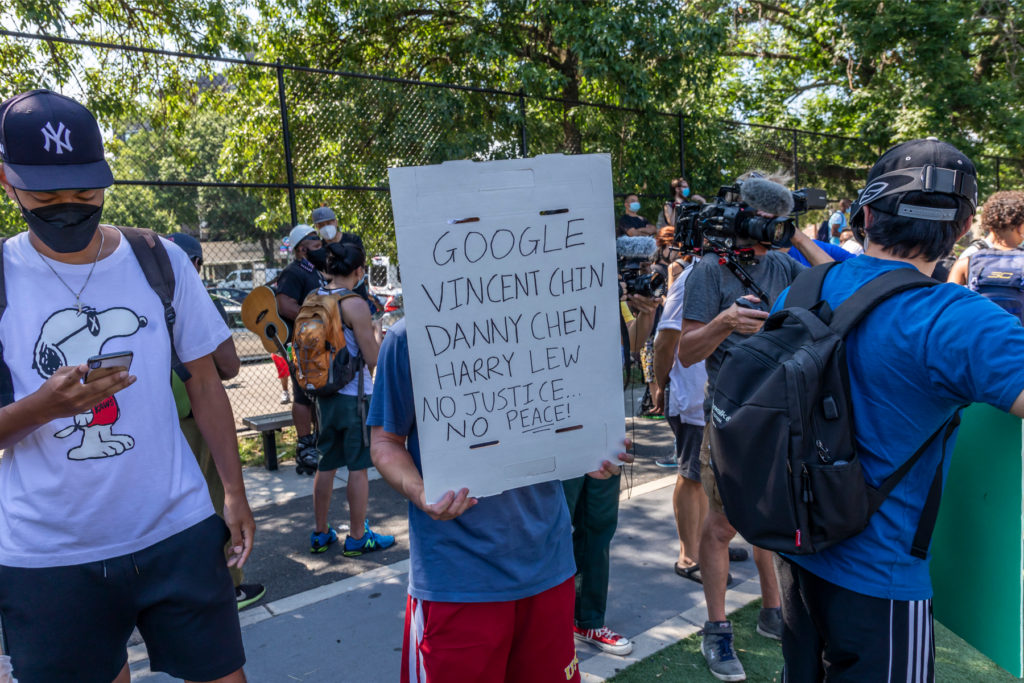

In January, Vicha Ratanapakdee, 84, was violently shoved by an assailant during a morning walk in the Anza Vista neighborhood of San Francisco and later died of his injuries. In Oakland’s Chinatown on Jan. 31, a 91-year old man was pushed to the ground by an assailant who attacked two other senior citizens on the same block. On Feb. 3, a 61-year-old Filipino man in Manhattan was slashed across the face by a stranger on the subway. He stated that he thought he was going to die, and nobody on the train helped him.

Anti-Asian hate crimes, primarily targeted at East Asians, have skyrocketed around the country in recent months in the wake of the COVID-19 outbreak. In the early days of the pandemic, racially-motivated attacks against Asian Americans were numbering over 100 a day.

[Read Related: ‘Model Minority’: The Myth That Negatively Affects all Minority Groups]

The rise in hate crimes against Asian Americans in response to the coronavirus pandemic speaks to a deeper problem, in which the term “Asian American” has become synonymous with the affluent Chinese middle-class and the rampant stereotype of the “model minority.” This is the idea that Asian Americans are perceived to have higher educational and financial success and fewer social and psychological problems than other racial groups in contemporary American society. Asian American Pacific Islanders (AAPIs) are a diverse group, consisting of more than 60 different ethnic groups speaking more than 100 different languages. They account for more than 5.6% of the population of the United States and have vastly different poverty rates when broken down by demographic/nation of origin.

The History of Discrimination Against Asian Americans

Asians in the United States may be deemed more “model” than other racial and ethnic minorities, but have only tenuously been accepted as American – a trend that reversed sharply in March 2020, when Rep. Paul Gosar, R-Ariz., tweeted about the “Wuhan virus.” We’ve seen multiple incidents of Asian Americans being singled out due to their perpetual “foreignness” throughout American history, from the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which remains the only federal law to deny immigration on the basis of race, to the internment of 110,000 Japanese Americans during World War II. Perhaps the most pronounced example of this dissonance was during the Vietnam War when Asian American soldiers in the US military suffered verbal and physical abuse from within their own ranks as a result of Anti-Asian xenophobia.

This current moment in history isn’t even the first time Asian Americans have been vilified as the source of disease and illness. Before the right-wing rhetoric of the “China Virus” and “Kung Flu” in 2020, we had politicians in 1876 pointing to the uncleanliness of Chinese immigrants themselves, rather than the poor sanitation infrastructure in those neighborhoods, as the source for an outbreak of the bubonic plague, cholera and smallpox in San Francisco. In 1900, after an outbreak of the plague in Hawaii, only Chinese residents were forced to quarantine and barred from travel to the continental United States. Officials in Honolulu then attempted to “sanitize” Chinese neighborhoods by setting fire to buildings where plague victims had died. The flames consumed a fifth of Honolulu’s buildings and over 5,000 homes.

More recently, decades into the well-established narrative of Asian Americans as the model minority, we saw an uptick in anti-Asian hostility and discrimination in 2003 following the global outbreak of SARS. Billed as the “Chinese disease,” the virus placed Asians and AAPIs under a microscope of contagion, ostracism and stigma, and images of buildings in Chinatown or Asian people wearing masks were widely used in media coverage of the outbreak. People stopped patronizing AAPI-owned businesses or refused to serve customers of visibly Asian descent.

Some argue that Asian Americans have consciously benefited from the model minority label, but a stereotype rooted in racism can never truly offer a buffer to systemic racism and inequity. AAPIs have long been used as an exemplar for racist ‘whataboutism’ to denigrate the Black and Latinx communities and promote propaganda that the American dream can be achieved by those who pull themselves up by their bootstraps and have strong family values.

False stereotypes about Asian Americans as a model minority also diminish the discrimination and racism that they’ve faced for well over a century and continue to face escalating incidents in 2021. Narratives of AAPIs in America as the “yellow peril” and as the “model minority” are diametrically opposed, and cannot and should not be allowed to coexist in harmony.

Showing Solidarity As South Asians

One of the first steps we as South Asians can take is to educate ourselves on the history of anti-Asian xenophobia in the United States and on the “model minority” myth and its consequences for Asian Americans.

We’ve seen an increase in attacks against Asian communities and individuals around the world. It’s important to know that this isn’t new; throughout history, Asians have experienced violence and exclusion. However, their diverse lived experiences have largely been overlooked.

— Twitter Together (@TwitterTogether) February 9, 2021

Stop AAPI Hate — a project based out of San Francisco State University that asks AAPI communities to self-report acts of hate and discrimination — has counted 2,808 incidents of anti-Asian crime since the beginning of the pandemic. But, co-founder and co-executive director of Chinese for Affirmative Action Cynthia Choi believes that these numbers are likely an undercount. One manner in which the South Asian community can show solidarity with their fellow Asian Americans is by encouraging those in our social circles who experience racially-motivated attacks to report them. Stand Against Hatred is a similar tracker by Asian Americans Advancing Justice where individuals can read about the incidents that have been reported.

Another way to support those AAPIs who are being targeted by harassment, bullying, verbal assault and racial slurs is to acknowledge that an act does not have to be physically violent to be traumatic for the victim, and encourage them to seek counseling, support or treatment for any trauma they may be experiencing. The Department of Health and Human Services estimates that only 6.3% of people over the age of 18 in the AAPI community seek and receive mental health services, as compared to 18.6 percent of non-Hispanic white adults.

Some educational resources and materials on ending the stigma around mental illness in Chinese, Hmong, Khmer, Korean, Lao, Mien, Tagalog, Vietnamese and Japanese by Every Mind Matters can be found here. A good resource for helping someone seek culturally competent care provided by the National Alliance of Mental Health can be found here.

If you live in a community where there have been multiple incidents of violence and harassment towards Asian Americans, you can help create safer spaces for them by providing them community resources. Ask elderly members of the AAPI community if you can do their grocery shopping to keep them safe from both the coronavirus and anti-Asian racism. You can band together with other like-minded individuals to create a response group that can make sure that should someone be attacked, they have access to a support network and resources to report a crime or seek mental health counseling.

South Asian Americans know all too well what stigma and discrimination feel like, but we have also benefited from the proximity to whiteness offered by the model minority myth, even though we as South Asians may have perpetuated casual bias against other AAPIs within our communities. It is therefore imperative, now more than ever, that we stand in solidarity with our fellow members of the AAPI community in condemning these racially-motivated hate crimes, harassment and violence.