Photo Courtesy of Shutterstock

U.S. Surgeon General Dr. Vivek Murthy recently warned of the increased rates of depression, anxiety, ADHD and suicide attempts in today’s youth. As an elementary school psychologist, I assess students’ social-emotional needs to improve their mental health and positive behavior. Starting my career at the height of the pandemic allowed me to see that children’s distress and trauma were exacerbated. Mental health stigmas persist, but it’s vital to address children’s challenges to avoid another crisis.

The Omicron variant threatens to further derail stability in schools, as remote learning may become necessary again to quell the pandemic’s new wave. With this, educators already sense the challenges ahead. This time last year, teachers grappled with how to navigate new technology, and families struggled to maintain a semblance of order.

My work, primarily with low-income children of color and children with disabilities (two populations disproportionately affected by the pandemic and mental health difficulties), highlighted the systemic barriers many faced.

[Read Related: COVID Continues in 2021, but we can Still Have Hope]

Food, job, housing and political insecurity contributed to a sense of isolation and stress. Inconsistent online logins impacted students’ ability to retain the curriculum, particularly those with special education services, such as speech and language, students’ occupational and physical therapy and counseling.

Targeted academic interventions, geared toward students already struggling to stay on grade level, were paused. Standardized testing for specific disabilities was cautionary, but social-emotional and behavioral support for all students and their families skyrocketed.

After months of changing from remote to hybrid models, most students have returned full-time. According to the National Institute of Health, more than 140,000 school-aged children lost caregivers to COVID-19.

Some kindergartners and first graders have never been part of an in-person class. Teaching basic social and pre-academic skills such as sharing, social distancing and sitting correctly in a chair for an extended period of time were paramount. School-based fine motor skills, such as handwriting, coloring and cutting were challenging. As the year progressed, difficulties with emotional regulation and social problem solving escalated.

Schools felt the simultaneous increase of disruptive behavior, struggles to stay focused and collective grief or burnout from educators who worked tirelessly over the past two years.

As children return from winter break, I reflect on how the pandemic compounds the struggles associated with youth growth and development. Learning healthy social skills, problem solving and reasoning, self-advocacy and coping are fundamental aspects that a safe, structured school environment can provide with in-person modeling and reinforcement. While some children thrived remotely, others’ risk of difficulties and delays intensified without the routines and expectations of a normal school day.

School-based mental health clinicians offer students evidence-based and culturally conscious strategies to support their wellbeing. Families may implement these to help instill the tools necessary for life’s challenges.

1. Acknowledge

Foremost, acknowledge that “negative” emotions such as sadness, worry and anger are normal and experienced by all. State that it is okay to feel these emotions and encourage the ability to make positive choices that help us deal with them.

2. Techniques

Teach a multisensory deep breathing exercise as a coping strategy and way to give pause. An example is “birthday breathing,” where the individual’s hands rest on their stomach and they inhale/exhale while visualizing blowing out a birthday cake. Another technique is “take five breathing,” where one hand is extended like a star while the opposite finger traces up and down the fingers, coinciding with deep breaths. Always practice this while calm as a means of remembering it when stressed.

3. Encourage Critical Thinking

To engage in problem-solving and self-awareness, encourage thinking about the “size of the problem.” Children learn that their reactions should ideally match the severity of the problem as opposed to getting stuck focusing on the negative emotions associated with it.

4. Emphasize Workflow

To aid with attention and work completion, offer motor breaks and set goals on how much work should be finished in a given time. Encourage the use of self-talk to work through the steps of a problem and designate specific workspaces devoid of distractions.

5. Check in Daily

Check in with children daily to build their emotional vocabulary. Have them reply in an “I-statement” form, stating how they feel and why.

View this post on Instagram

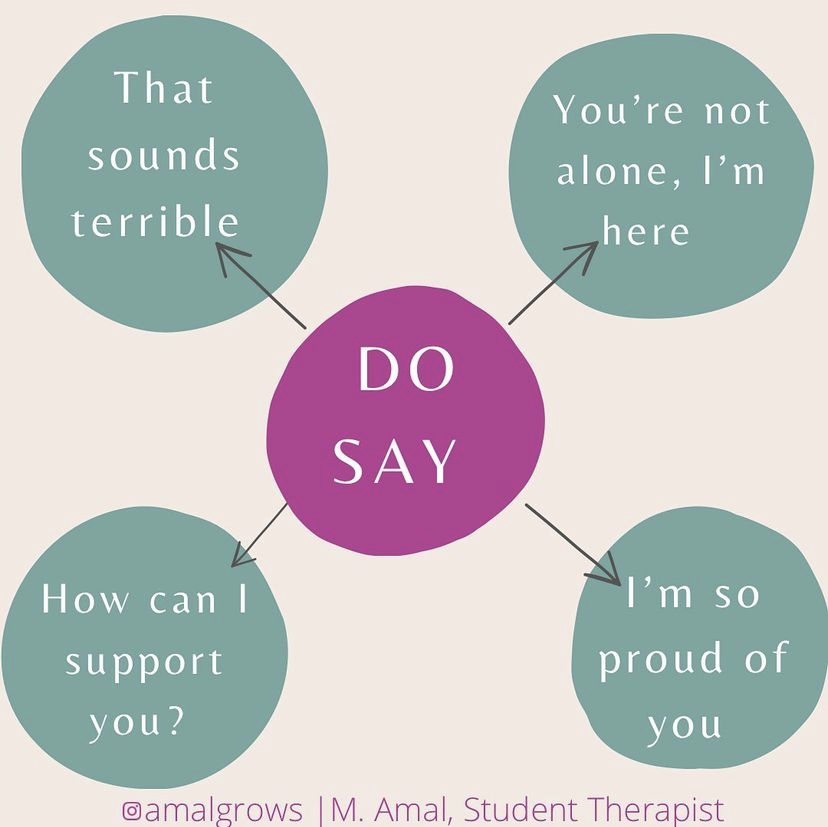

6. Emphasize a Support System

Advocate to children that you are there for them always, despite mistakes and frustrations. Tell them that it is a learning process and it is important to keep trying even when our emotions change and we don’t feel 100%.

Optimistically, all children are capable of building resilience. They take their emotional cues, from reframing negative thoughts to showing empathy and admitting wrongdoing, from the individuals around them. It is a two-fold responsibility that adults within the home and school environments collaborate in, promoting a society-wide effort of positive youth mental health. It is time to combat the negative connotations surrounding mental health and offer children the support, resources and positive role models whenever needed.