Among the global South Asian population, many, including myself, have noticed the particularly brown brand of obsession with reputation. From childhood to now, I have felt like a prop used by my parents to show off their success as guardians. Their motivations to push me in terms of my education have partially felt as if born from their lust for, not only the approval from but also the triumph over others in their social circle. My achievements were exaggerated, with anything less than stellar either manipulated or straight up thrown under the rug.

This environment makes for an interesting experience and relationship with growth. One is perpetually burdened by the pressure to the point where you forget that your goals are your own. Stress amounts without bounds when you compulsively compare yourself to your competitors cousins and family friends. The way my activities are manipulated causes me to project the imaginary future where my mum is sitting with my masi (aunt), recounting the ideal outcome to a task I am nowhere near completing.

This helped me realize that this compulsion trickles down the family tree, meaning my parents had similar experiences. Where else would you learn how to parent other than from your own experience of being parented? I thought deeply and tried to pull back the curtain on why this mentality has festered and remained in our community over so many years. Sure, as the years go by, people learn from the mistakes of their parents but the jerk-reaction to protect reputation is something I still observe and something I went searching for reasons behind. My theory starts with the Raj.

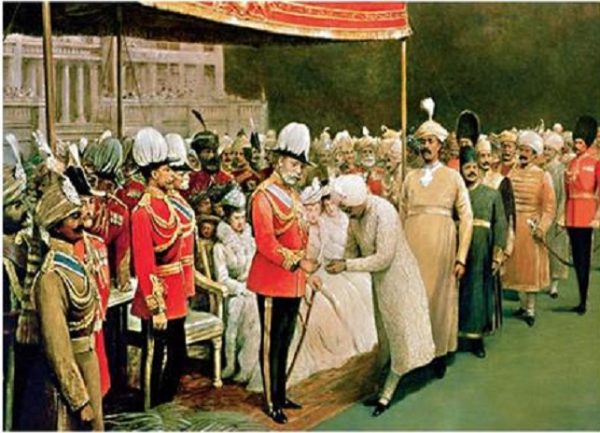

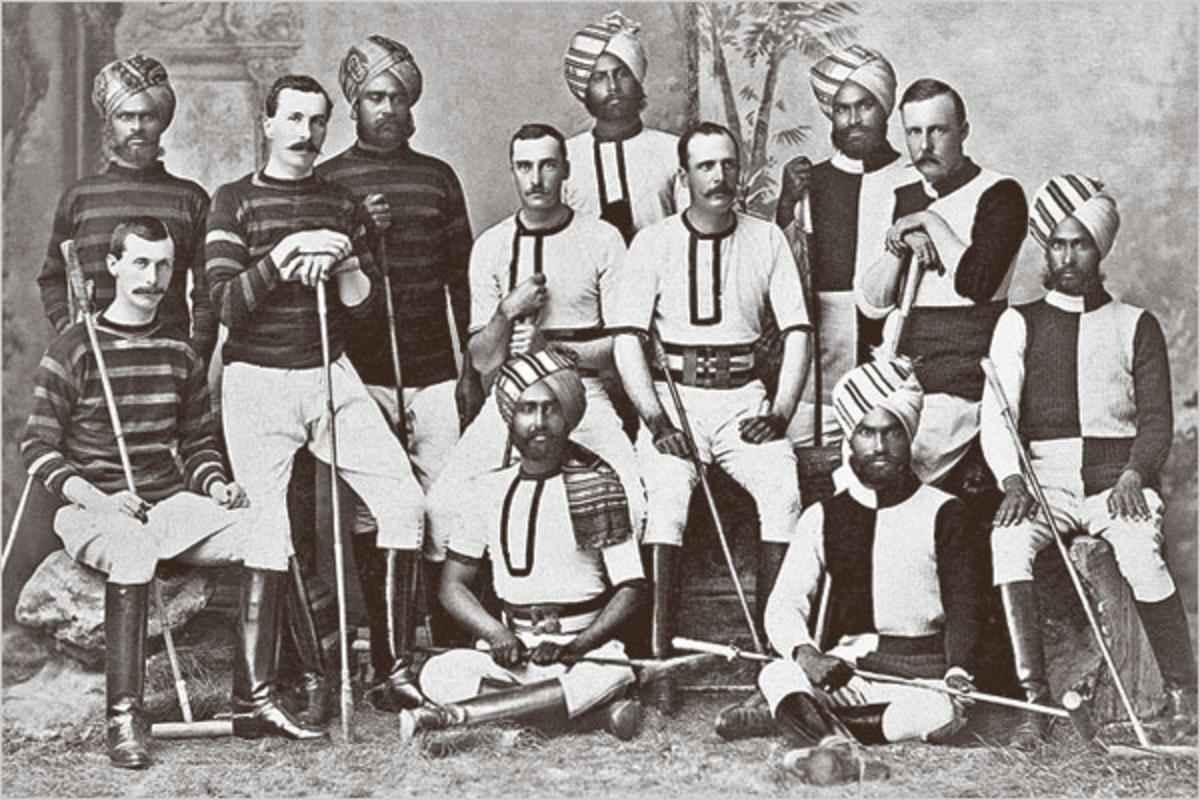

Actively building a class system in India, the British birthed the Babus. The Babus acted as civil servants for the British government, perpetuating their ideologies to the masses. This ideology included the exaltation of the paler skinned as those with the richest intellect and truest taste in the nation – a standard that white people feel entitled to perch on to this day.

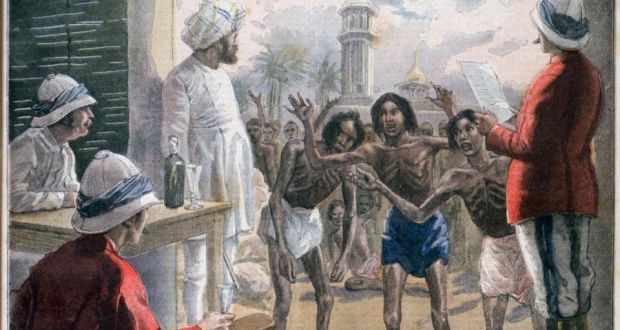

The effect of the establishment of this societal hierarchy helped the Indian public to internalize the white man as the benchmark of success and culture. With the Babus being as close to this idea that an Indian could get, and with the responsibility and power of being a Babu being set on a pedestal above what millions of Indian residents could reach, societal reputation would have become increasingly important. The British were responsible for an uncountable amount of Indian deaths at the time, making a climb of the social ladder a scramble for life.

Could it be possible that this mentality has stayed with our community after so many years? Manifesting itself in the manner in which so many of us treat our reputation as our livelihood. The only means of escape seemed to be devoting yourself to prove you were a class above the rest of the country. With the migration of Indians towards the West in recent years, living as an Indian amongst the race we were taught to be superior can call on a necessity to prove your value in this society—a value we were stripped of and was broken to pieces all those years ago.

The rapacity of the British drove them to strip the Indian public of their strength—and they succeeded. Our ancestors were made to believe that their culture was primitive, that their ideals were basic and that their very skin tone made them lesser. This not only affected the perception of one’s self but how that person would see other Indians.

Inventing the facade of unworthiness amongst Indian communities allowed the British to manipulate them. A community without unity and self-esteem will have fallen without a fight against the British regime. Internalizations this strong did not disappear when India gained independence and was split in half. This may have created more animosity amongst brown-skinned people in South Asia, further propagating the wave of spirit breaking British ideals.

[Read related: The Colonial Eye: As the British Saw and Described Indians – The Delhi Durbar of 1903]

This, of course, lives on to this day. Though each generation further away from the times of the British Empire builds an extra mental layer of self-esteem, one can still observe how South Asians will take any opportunity to turn up their nose at another South Asian. Whether that person is a stranger or a family member, it is almost impossible to deny the judgment found within the South Asian community. We act like crabs in a barrel, kicking our way towards our perceived idea of success at the cost of so many we share a skin tone with. Rather than building a community to rise together, we would rather be the sole victors, a mentality instilled in us from colonial times.

The effects of colonialism live on in every community it ever affected. These effects do not simply drown out over a few years, how the British reset the mentality of our ancestors remained attached to us through generations, many of us unaware that the actions of people long dead subtly control our thought processes every day. This may seem far fetched to some, but one can easily observe how age-old ideals survive almost infinitely.

To this day, there is tension between Hindus and Muslims, a statement that could have been made more than 100 years ago. Still, many white Brits see India as a country populated by people of lower intellect. Even now, the idea of success in an Indian person’s mind is likely to be defined by a white man.

The British set themselves as the peak of the class system, looking down on the Indian people who were made to believe they were lesser. They turned communities against each other, using religion as the knife to bisect the nation, thus establishing a generation of Indians programmed by the British. As this programming morphs through generations, and South Asians migrate more and more to white-dominated nations, the desire to feel accepted and to make it known that you belong in what is perceived as a higher class of society becomes prominent.

[Read related: The Colonial Eye: As The British Saw and Described Indians]

Your societal reputation is what defines so many South Asians in the west, the effects of which can hurt so many people around them. How many times have we heard stories of children forced into careers by their parents, or have we been the kids made to be doctors and dentists just because they are considered acceptable, money-making, intellectual fields? This individualistic thinking could be a symptom of the selfishness prescribed to the “crabs in a barrel” mentality.

When distaste for the next person is combined with an innate desire to be accepted by those whom you placed as the benchmark for success, the people around you suffer. Understanding the possible causes of the obsession with a reputation in the South Asian community has enabled me to make a conscious effort to reduce the control my ego has over me, and understand why it has such a bearing on the lives of others. I hope, as South Asians, we can strengthen our sense of community in the coming years and seeing a step up the social ladder as an opportunity to bring others with you, rather than a chance to feed your ego.