*Quotes have been edited for clarity*

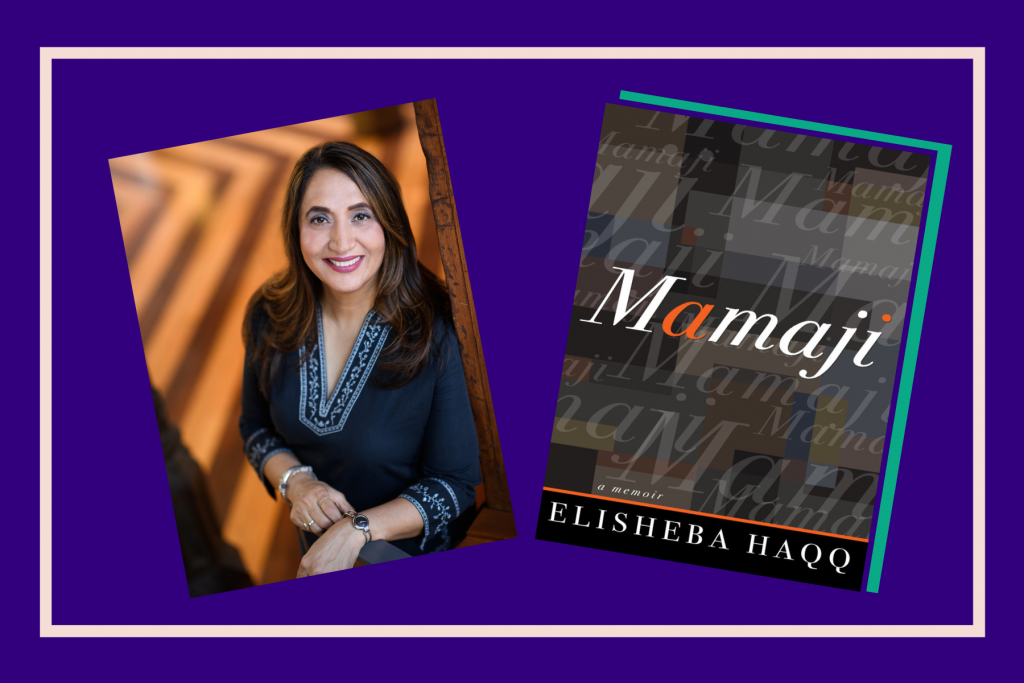

The truth is, you never really know someone from the outside looking in. On that hot August afternoon, adorned in a beautiful pink scarf, Elisheba Haqq sat at a small contemporary café in the middle of a small bustling town in central Jersey called Metuchen. In fact, she was waiting for me. On the outside, we may have looked like a strong South Asian mentor and mentee duo, but really I was there because I had just finished reading her memoir and I felt a strong pull to meet with her in person.

Elisheba Haqq’s debut novel, “Mamaji,” is an all-encompassing memoir that details the heartbreak and healing of a family that lost their mother at an early age. Only about a year after moving to Minnesota from Chandigarh, the mother, or Mamaji, contracted rare cancer and passed away within a year. Haqq was just three when this occurred. Like many traditional South Asian households back in the ’70s and ’80s, the backbone of the children’s youth was the nurturing presence of their mother. The passing of Haqq’s mother in a foreign land and her father’s immediate remarriage were the catalysts that began years of cultural isolation and an oppressive home environment.

Completely drawn by Haqq’s voice as the youngest of seven motherless children in a mostly white Minnesota town, I read the entirety of the memoir in one sitting on a dreary afternoon. After I finished reading, I immediately asked to interview her. We sat down with our coffees in hand and began a three-hour discussion about her journey writing the book and all the emotions in between.

View this post on Instagram

Haqq opened her memoir by not only highlighting the importance of family but also the importance of reconnecting with Mamaji’s family after years of not speaking. Rather than moving back to India when Haqq was three years old, as her mother requested on her deathbed, Haqq’s father lost their palatial family home in Chandigarh upon his remarriage. With that, his growing children lost their only connection to India and to Mamaji’s entire side of the family.

Read Related: [Book Review: Grief and Loss in ‘Wave’ by Sonali Deraniyagala]

I asked Haqq how she felt upon contacting Mamaji’s side of the family, one of many freedoms she received after getting married.

I felt like a stranger and I felt a huge sense of loss. I couldn’t really go back and hear what they had to tell me. That was the first time I had been in my mother’s house. It was the first time I had talked to someone who had known her and loved her. My mom’s sister was telling me things about my mom that a normal person should know about your own mother. I also felt like she had been waiting so long, too. She had been waiting for me and my siblings. It was a very momentous moment. It’s hard for me to really put it into words, but I tried to in the memoir and that’s how it opens.

Delora, the woman whom Mr.Haqq remarried, created a divide within the Haqq family using emotional manipulation and pure cruelty. Her actions were no less than a classically villainous step-mom from a Cinderella movie, and she even has a wicked name to couple her personality. From essentially withholding the more edible food from the Haqq siblings to feed her only child, Joram, to financially controlling them in adulthood by having each Haqq child hand over their paycheck without a decent allowance in return, Delora created a grotesque caste-like divide between the seven Haqq children and the rest of the family (Joram, Mr.Haqq and Delora). With each event in the book, it becomes more apparent that Mr.Haqq’s physical and emotional absence allowed Delora to continue mistreating his own children.

Read Related: [Jennie Gungiah’s Memoir ‘The Immigrant: A Journey of Good Hope’ is a Must Read]

Humans are so fallible, and my father was fallible. He wasn’t correct all the time. He was making huge errors as a parent. So for me to put all my faith in my dad, that was a really bad thing to do. I do regret that. I regret that I wasted years, you know, treating him as if he was God.

Not only are the sibling relationships explored, but the dynamic relationship between child and parent is ultimately questioned. Many times throughout the memoir, the callousness of Mr.Haqq is heartbreaking.

He wanted to maintain the blinders and just keep going forward because, you know, his error was that he trusted her. Her error was that she just didn’t like us. They knew what they had been doing, but I really do feel that she was doing it purposely, he was purposely negligent and I think it was easier for him to keep the peace.

“Mamaji” brings to light the inherent problems in traditional households where children, especially girls, are not given the liberty to make decisions for themselves and are viewed as liabilities until they are married. Their value is measured in how much they can give back to a household, and building a career comes second to getting married young. During my time with Haqq, we reviewed how, even now, many South Asian females get married to seek liberation.

Upon asking how Haqq and her siblings maintained their grit and integrity despite the unfairness before them, she simply replied that faith, her mother and humor are what bonded her to her siblings for life.

I think we all had a very strong faith. We all felt that this was a very temporary situation and that we were bigger than the limitations of that situation. We really did believe that God had made us for something bigger than that small house and that small situation with those small people. The second thing is, I feel my mother had a lot to do with it. Although she was gone she left us with that connection, those relationships, the fact that we all knew and loved this person, some of us knew us better knew her better than others, but she was what bound us together. It was a sit down, let’s talk about it and [we] decided that we are going to be more like her. We actually sat down and said that no matter what happens, we’re going to stick this out together, and even if we hate each other for 20 minutes, we’re going to be okay later.

It was refreshing to see how Haqq channeled the restrictions she grew up with, and in turn, raised her sons to be independent men who can pursue their interests. Haqq also believes that South Asians, including her sons, should acknowledge and utilize their privilege to help those in need.

My concern with my kids was their character. What kind of people were they? Were they kind, were they compassionate, did they know how to contribute to their community? I’m not talking about Indian community. I’m talking about where they live, the people that they know, people who are living in poverty, people who are have less than they do.

[Read Related: Empowerment Between Generations: Moms and Daughters]

Haqq and I kept circling back to a constant theme of validation. We were taught to seek validation from our parents, then our husband and then our children. Women were to be the peacemakers of the household and the ones who front the burden of others. While talking about how she raised her kids, Haqq drove home the point of letting them be independent decision-makers and seek support rather than validation.

I think that is the lesson of the book: you can seek validation from your dad. That’s not good. You seek validation from your parents, that’s not good. Your children. That’s not good. Your husband. That’s not good. Really, the only person that I feel is appropriate to seek validation from is God, because that’s the only place that you can go where there’s no disappointment.

Walking away from that meeting, I was touched and humbled. My heart went out to young Haqq and her family. Like so many others who have lost significant ones, their lives forever changed in one instant. An ode to family and motherhood, Haqq’s words carry pain and devastation, grief and solitude, courage and integrity. The palpable sadness from Elisheba and her siblings consume the pages and brought me to crevices of their past.

You can follow Haqq on Instagram, and buy “Mamaji” when it hits the shelves in October 2020!