As schools, gyms and restaurants reopen across America, the COVID-19 pandemic continues to claim lives. Each day, more than 700 people in the U.S. are dying from the novel coronavirus pandemic, a higher rate than in any other developed country in the world. The COVID-19 death rate in the U.S. is 50 percent higher than in Spain and Israel, the two developed countries with the next-highest death rates. It is becoming abundantly clear that the federal government’s grossly inadequate response is both intentional and fatal, as President Donald Trump admitted in an interview to journalist Bob Woodward that he tried to “play down” the risk of the pandemic so as not to “create a panic.”

Public health experts, including Harvard Global Health Institute faculty director Dr. Ashish Jha, noted that the Trump administration is uniquely responsible for the abysmal case and death rates in the U.S. and that under different leadership, the country would not be suffering as severely from the virus.

While the Trump administration’s inaction has caused widespread harm throughout the country, communities of color, particularly Black communities, are bearing the brunt of the tragedy. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), American Indian, Black and Hispanic/Latino communities are reporting COVID-19 cases at over two and a half times the number of cases of their white counterparts. Black Americans are more than twice as likely to die from COVID-19 as compared to white Americans, the largest comparative death rate of any of the aforementioned groups. Asian Americans are also suffering disproportionately, as they are 1.1x more likely to catch COVID-19 and 1.3x more likely to be hospitalized due to the virus (though there is no disparity in COVID-19 deaths between Asian Americans and white Americans).

[Read Related: 4 Concepts to Help you Adjust to Your new Normal During COVID-19]

These are meaningful statistics with deep personal impacts, as nearly one-third of Black Americans know someone personally who has died from COVID-19, compared to 9 percent of white Americans. The numbers illuminate the duality in lived experience between white and BIPOC (Black, Indigenous and people of color) Americans.

White Americans are essentially living in a different reality altogether, a premise that reveals itself in their policy priorities. A poll conducted by The Washington Post in June asked respondents whether it is more important to try to control the spread of the coronavirus or to try to restart the economy, even if one hurts the other. 83 percent of Black Americans said it was more important to try to control the spread of the virus while only about half of white Americans agreed. Black Americans have been forced to confront the tragedies of coronavirus-induced death in their communities to a much greater level than white Americans, which explains why they are more concerned about fighting the virus.

The disparities in cases, hospitalizations and deaths from COVID-19 between white and BIPOC Americans stem from several factors. Scientific American attributes the inequities to the fact that many BIPOC work in “essential” industries where exposure risk is higher are more likely to lack access to health or life insurance and suffer from higher rates of underlying health conditions such as hypertension and heart disease.

The prevalence of underlying health conditions in these communities in the first place is a result of decades-long policies such as redlining, which forced people into overcrowded housing with more severe levels of air pollution. The federal government’s COVID-19 response, including the Families First Coronavirus Response Act and the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act, has been focused on economic relief rather than providing healthcare benefits to individuals at risk. The government has provided capital to small-business owners (leaving arguments about the efficacy of that relief aside) but has left uninsured front-line workers out to dry.

[Read Related: Why the Fight Against Coronavirus is the Fight of all Ethnic Minorities]

Poverty and educational barriers also make it more difficult for many BIPOC to take important safety measures; for example, social distancing is much more difficult in a small, multi-family apartment or home.

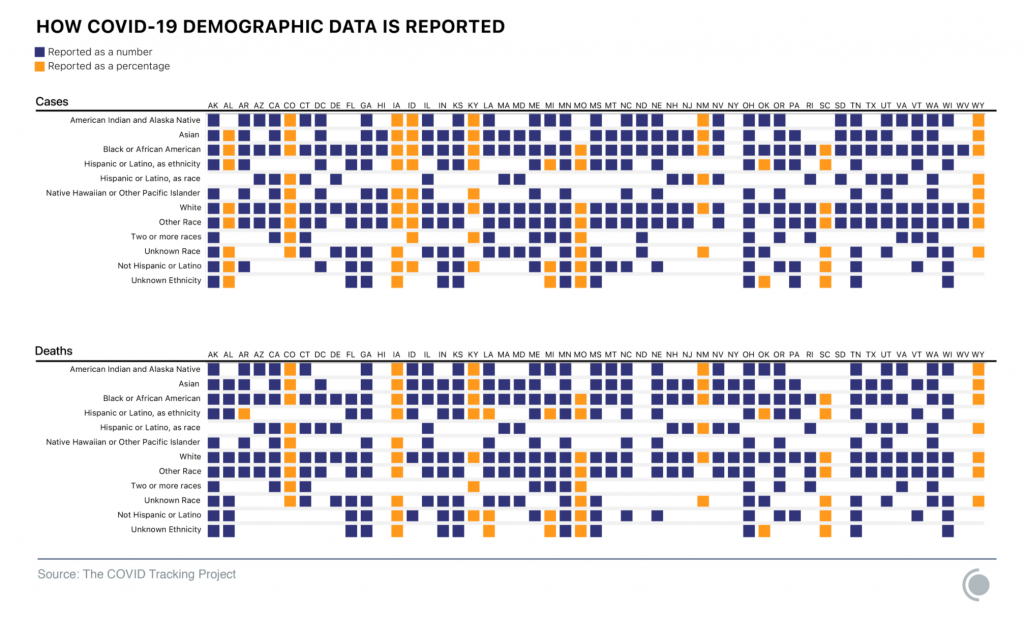

The lack of comprehensive racial data relating to COVID-19 in the U.S. poses a huge challenge in addressing these disparities. Often, we must grasp the scope of the problem on a granular, local level before applying targeted solutions. Only six U.S. states have released breakdowns of COVID-19 testing data by race, as per the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine. The COVID Racial Data Tracker, run by The Atlantic and Center for Antiracist Research at Boston University, explains that the inconsistencies and omissions in state-level data on the coronavirus mean that we have race and ethnicity data for only two out of five U.S. cases.

New York state still fails to report race and ethnicity data for all of its COVID-19 cases. The COVID Racial Data Tracker team provides information on its website with resources for those seeking to encourage states to take action in releasing the latest race and ethnicity data.

Without more robust reporting, policymakers, employers and leaders cannot as effectively implement the detailed solutions needed to address racial disparities in the pandemic’s outcomes. While we know for a fact that communities of color are hurting the most, we lack the information to identify the most vulnerable populations on a local level that need additional resources such as personal protective equipment and testing. Gathering better data is an important step forward in helping the most vulnerable communities protect themselves from COVID-19.

Until better protections for essential workers and those living in poverty are implemented, health outcomes for BIPOC in the U.S. will continue to differ starkly from those of their white counterparts.