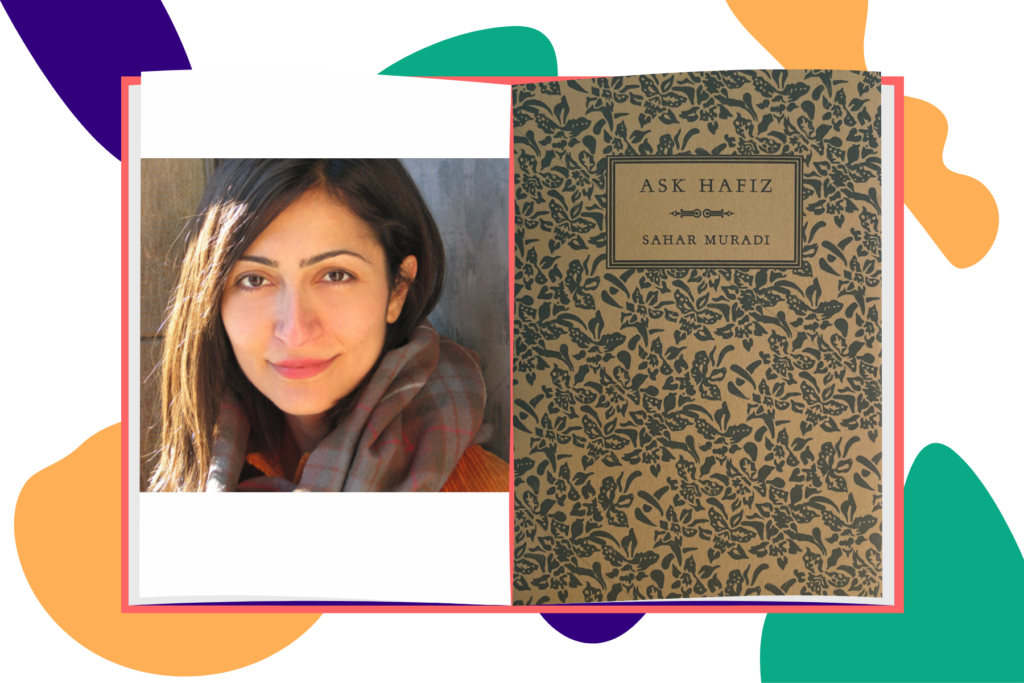

Writer Sahar Muradi—who straddles multiple worlds and in-betweens—calls her siblings “co-travelers” in the Acknowledgements section that follows the conclusion of her recent publication “Ask Hafiz.”

“Ask Hafiz” is an honest artifact that retells her (nuclear) family’s journey from Afghanistan to the U.S.—by way of Kabul, through the Afghanistan-Pakistan border, to Peshawar, Karachi, then Colombo, Sri Lanka, and finally—to NYC.

“Co-travelers.” This statement aptly captured a fog of feelings that I couldn’t contain long enough to give language to for most of my life. The term relinquishes responsibility and invites the collective, which feels at least partially relevant during this time in Afghan and world hxstory.

As someone who also straddles hyphens, I’ve never called my siblings “co-travelers” but I ought to. While we haven’t journeyed in the exact same way as Muradi and her siblings have, the terms “sibling,” “sister,” and “brother” just don’t suffice in encompassing the weight of such a relationship within the diaspora.

Effectively, we are all translators, code-switchers, trail-blazers, guinea pigs. And from that stalks up resilience. As I’ve aged and matured, both with and against the currents of time, I have come to realize what this life truly is—a journey. That’s it. So we’re all travelers.

Yet “Ask Hafiz” hones in on Muradi’s journey—in particular, which is one of forced migration.

[Read Related: Book Review: ‘Here We Are’ by Aarti Shahani, a Memoir of Untold Immigration Injustice]

To love and have a love for something are two different kinds of love. With that said, I have a love for Muradi’s journey, as difficult as its parts are to digest. While I have a love for Muradi’s journey, I love her love for her homeland. Person-to-land love is incredible. It’s beautiful to read about and I was drawn to that effect “Ask Hafiz” conveys.

Although my homeland is a different one (and if I pluralize my homelands, on the whole, they are still different—albeit neighboring, overlapping, interwoven), Muradi’s dedication to lineage speaks to me and would speak to anyone avenging ancestral wounds through radical decolonization of self and origin.

But what is a homeland? What is ancestry? What is radical decolonization? Self and origin? For me, is it my parents being born in India? My grandparents being born in (modern-day) Pakistan? Or is it my uncle, years before he passed, sitting my sister down on a cot in Bombay and telling her that we originate from the Ottoman Empire—but providing no tangible evidence other than his testimony that is now, concrete as vapor with his passing?

[Read Related: ‘Little America’ Shows 8 Real, Complex & Endearing Stories of Immigration Worth Watching]

As it turns out, homeland is queer. It’s movement, it’s unclear, it’s imagined and real—and real and imagined. Some of Muradi’s pages are dedicated to borders, some dedicated to neighboring countries, some dedicated to international flights.

It also turns out, however, I didn’t cross paths with Muradi first on the printed page. Months ago, I was allured to a Kundiman workshop titled “Forms of Liberation: The Ghazal and Landay in Perspective.” I entered with a basic prior knowledge of Ghazal and none of Landay, and I wished to grow my understanding. The stars aligned and it manifested. And that’s how Muradi and I first met; we co-traveled, briefly.

In her short narrative “Ask Hafiz,” Muradi promises to fulfill and satiate a ravenous craving for a journey. In her 34 pages of prickly text, she has written “a migration story told through poetic divination,” as she puts it. Muradi centers on the divine, the divan.

Specifically, “Ask Hafiz” refers to the cultural tradition that Muradi’s “Madar” (mother) would engage in when tasked with difficult decision-making—or when at a crossroads—of sorts. Madar would ask Hafiz, the Persian poet whose ghazals are recorded in the Divan of Hafiz. She would turn to his writing, his literature. His verses are scattered throughout “Ask Hafiz” and translations are provided for those (like me) who cannot immediately access the wisdom.

I’ve collected ambiguous hyphens in my identities over the years. It’s not my fault; not everything is clear-cut, especially the more you learn. I grew up with a very general understanding of divan but did not grow up with the ritualistic practice itself. I did grow up with an unwavering awareness of the mystical, the auspicious, the pesky nazar that we love so much—along with the love for its immeasurable energy. Its immeasurability is our truth.

I grew up with a mom who sways when she prays. I know trance—both secondhand and first. While this is not identical to the divan of Hafiz, it’s a testament to the fact that there are times when we find ourselves coping and we’re short on solutions. When we push ourselves to enact our deep-rooted survival tactics to make sense of the status quo and proceed with the restraints of our realities.

[Read Related: The Poetry of Arranged Marriages & Falling in Love]

Sometimes decisions are above us. We must give in, to a higher power. Why create answers when we have unfurled from a legacy of people who always have and always will?

For this reason, now that I’ve relished Muradi’s words, I am making her words co-travelers and sending them to my friend Tara who I just FaceTimed this week. Tara repeatedly mentioned finding herself in a liminal space.

The nuisance of liminality. What was, what is, and what the future holds—are all causes for anxiety. I’ve been there. It sucks or at least feels like it does. Luckily (or unluckily) destinations are not always the greatness that we make them out to be. We are all capable of home. Capable of home. And heritage.

Tara, who identifies as Persian and Iranian, did grow up with the divan in her household. She told me that its utility was especially relevant during times of solstice. I hope it serves her in the way it served Madar, and Muradi and her siblings, during their difficult times, most of which were inherently liminal.

To follow Muradi’s writing AND to learn about important ways to support Afghan lives right now, please visit her Instagram page. And special thanks to Thornwillow Press for generously donating the 103rd imprint of “Ask Hafiz” to saahil m. at Brown Girl Mag.