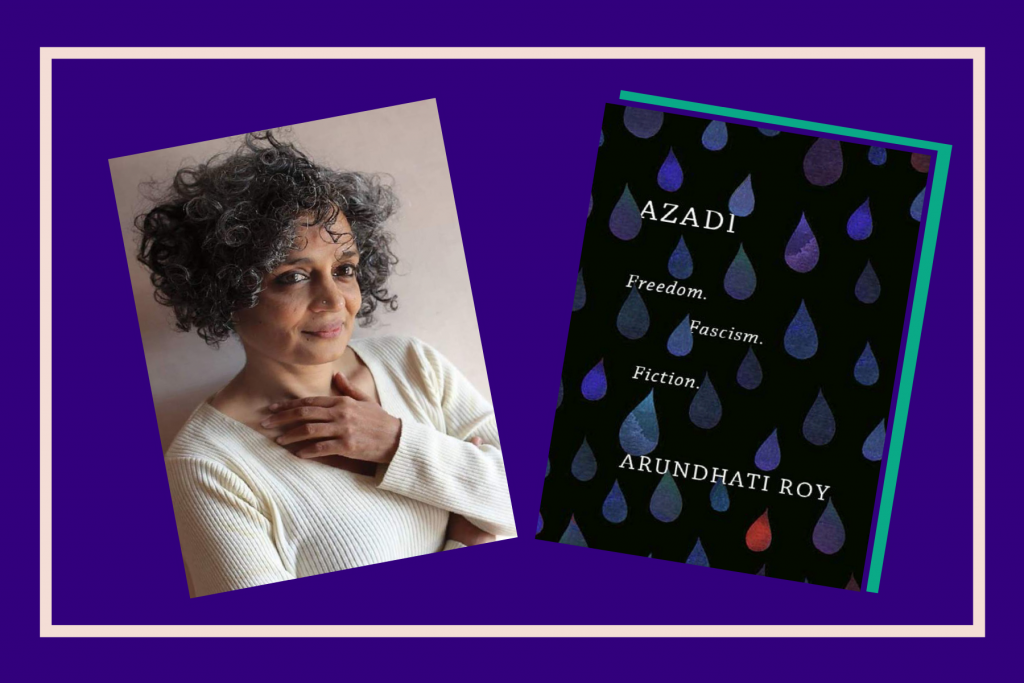

I come from two mothers: my motherland and my humxn mother. Both are connected, showing that nothing comes in just twos—there’s space in-between, bridges. So while Arundhati Roy’s recent release “Azadi: Freedom. Fascism. Fiction.” explores the space between the fiction-nonfiction binary, this review explores the space between my duality of mothers in relation to the book’s themes of freedom, power, resistance and dissent in South Asia.

Roy is no stranger to literature. In fact, she story-tells unapologetically. “The God of Small Things” and “The Ministry of Utmost Happiness” are prolific masterpieces of hers that you’ve likely read. I still remember where and how I was positioned when I read both of these narratives. I even remember what the days felt like. Roy’s writing has a tendency to change my life over and over again. “Azadi” changes my life, but in a different way.

Roy named her book based on the Kashmiri cry for freedom. It is primarily a collection of academically cited essays about political realities in South Asia. Roy discusses communities that don’t want to be a part of India but are forced to. She also discusses communities that want and deserve to be a part of India and are currently not being allowed to.

Roy shows how citizenship is the right to have rights. In her nine essays, Roy hxstoricizes the concept of freedom through both fact and fiction. She embeds passages from “The Ministry of Utmost Happiness” to show the politicized nuance that can be found in fiction.

[Read Related: Book Review: ‘The Death of Vivek Oji’ as a Site of the Reincarnation of Memory]

Roy starts approaching this nuance first through language and later through scenes and characters. She deconstructs the irony behind her liberative writing being in English—the language of the universal oppressor. For someone of the subcontinental diaspora (who can’t fluently speak any of the regional languages), this was extremely relatable. While “Azadi” is different from Roy’s acclaimed creative nonfiction style, this must-read hits home. Period.

I like to believe that among my South Asian peoples, I stir the pot in ways similar to Roy. I self-identify as a professional headache-inducer for aunties, uncles and everything in-between. By straining to make sense of our messy world, I even give myself headaches. This book review trudges through some headache-inducing life events to arrive at Roy’s call to action.

My ethnolinguistic community has been unquestionably affected by Partition—a Partition that turned us into refugees. Our “motherland” consists of scattered and diasporically blood-related bodies rather than a geophysical place.

At least we have a WhatsApp group where our hearts and minds can interact. With 2020’s unavoidable call for South Asians to finally reckon with social justice AND injustice, this WhatsApp group has been popping off lately.

Months ago, out of the blue, someone in our WhatsApp group forwarded a video clip praising Modi. One auntie, who otherwise strikes me as entrepreneurial and progressive responded, “Great. I am proud of our current Government. Another feather in our hat.” I was appalled by her response. My intuition had apparently misclassified her politics. She even capitalized the word “government” as if it’s a word deserving of heightened value.

I felt the need to first understand the video before judging too quickly. I clicked on it, but it was in Hindi so I couldn’t understand a thing.

I responded to our group, “What are you proud of, Aunty? I don’t speak Hindi but I’m anti-fascist and therefore anti-Modi. However I’m curious what specific policy this video discusses that creates a sense of pride.” I intended to invite conversation while being clear on my stance.

I was then gaslit and instructed not to start a political debate. I promptly received a private message from my mom, reminding me to “not go so hard” and start “cross-questioning” elders. She told me “Make your point politely, in a soft way,” reinforcing that respect for elders is crucial in our culture.

[Read Related: Books and Borders: a Tamil Migrant About Life in the Sri Lankan Civil War]

I told her “thanks” knowing very well I’m incapable of ever being that graceful. I was also annoyed that I was hushed when my intention was simple curiosity. Somehow, asking an elder to provide more information explaining their own statement was perceived as rude.

A promisingly cooler pseudo-auntie privately messaged me saying, “So the video is basically about Modi’s Air Force 1 plane.” In a sarcastic-sounding tone she followed saying, “We just like [that] we have a private jet for our big guy.”

I found this hilarious. The video was never about a commendable policy. The “feather in our hat” was about a plane that none of us can even ride. So how was this a feather in “our” hat? Who, exactly, is our?

My gracelessness continued to push back, while others reinforced the existing group agreement of not sending forwards. As a result, we never fully addressed the political friction. We never fully dissected the meaning of freedom.

It’s too bad that we’re Brown and perpetually impassioned by the spirit of rebellion.

A second forward was arbitrarily sent. This time, the video was celebrating the establishment of the Ayodhya temple. A few in my family supported it, a few didn’t. Debates ensued. The No Forwards agreement was reinforced once again. My mom chimed in claiming that deviation from the No Forwards agreement shouldn’t be objected to because the construction of the Ayodhya temple was a particularly hxstoric occasion.

Another No Forwards agreement breach followed. This time, it was with baseless, eye-rolling garbage claiming Kamala Harris is a Hindu-hater. And yet another messy conversation unraveled. My righteously woke uncle shared a sentimental story after already having lectured us on the divisiveness of “we” vs. “them” rhetoric—a point which my mom contested against. My politically-engaged sister was summoned by the entrepreneurial auntie to sprinkle well-informed Kamala facts over our conversation. A vague “respect for others opinions” kept being voiced as the blanket goal. Nobody acknowledged how neutrality is a conceptual façade constructed by the colonizer himself.

And then someone’s birthday passed and the WhatsApp group morphed into a living birthday card. While all this was happening, my mom randomly messaged me asking, “Who told you Modi is fascist?” as if someone needed to tell me this in order for it to be a fact or simply my opinion. I sarcastically responded in two words: “Arundhati Roy.”

And now, coincidentally after reading “Azadi,” I know my frustrated response was in fact a prophecy to the book’s prime utility: Roy wonderfully argues how Modi is indeed a fascist. So, mom, please read “Azadi” to have your question answered.

For emotional support, I messaged the cool pseudo-auntie expressing my wish that Arundhati governed India. We immediately acknowledged that she would most definitely get assassinated. I thought this because she’s a revolutionary. My pseudo-auntie thought this because she’s a womxn.

Freedom is intersectional. “Azadi” will likely mean something different for every person who reads it. Upon hand-delivering a copy of “Azadi” to my mom, she made a face of disgust and said, “You know I don’t like what she writes.” I still hope my mom reads it and I hope she derives meaning from it. Truth-telling is never an easy task, nor is experiencing a rude awakening. But we all have to, eventually.

[Read Related: 23 Must-Read Books for Every 20-Something South Asian American]

For me, I took away that casteism is a misnomer when considering the bigger problem. The real problem is Brahmanism. India, like the U.S., faces a supremacy issue. Arundhati proves this through her essays. She questions language yet she uses language as a tool to explore the humxn condition of fascism. She describes fascism as a feeling, since it has been such a pervasive pattern throughout humxn hxstory.

If fascism is indeed a feeling, I hope it’s fleeting. Because, as the book shows, a Muslim genocide sits on India’s eventual path. We need to change ourselves or change our path because the two cannot collide. It cannot happen. It would be devastating.

As Roy puts it, “India is fighting for her soul.”

I’ve worked hard to build my life in such a way that I don’t have to interact with Trump supporters, Republicans, or U.S. conservatives pretty much ever. Thanks to my privilege, progress and personal motivation, I’ve mostly been able to choose my tribe.

But I know this is not the case for everybody. Through dual motherhood, I currently interact with active and passive Modi supporters, BJP party voters and conservatives within the South Asian context (in addition to left-leaning liberals, progressives and radicals).

In some ways, I’ve been able to live in my head—the fictional place I’ve reimagined for myself. In some ways, I haven’t. Thus, freedom is about fullness. It is about who we want to be and how we want to live.

Arundhati concludes “Azadi” with the pandemic. She asks you what you will take into this portal and what you will leave behind. Who and what will surround you as we move towards this undefined future? Personally, I hope it’s a place where “Azadi” is not an essential.

But today it is—and it’s a family read.

Purchase a copy of “Azadi: Freedom. Fascism. Fiction.” from Penguin.