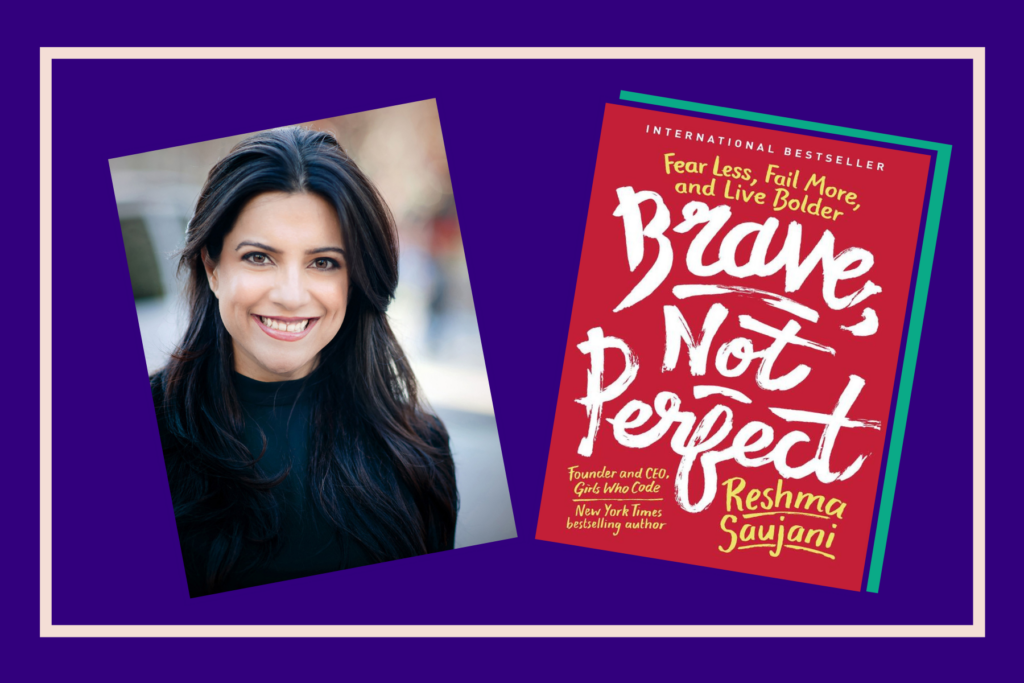

Join us at our second virtual phone bank on Monday, November 26th at 3pm PST/6pm EST to target Pennslyvania, a battleground state with our friends at @southasianwomenforbiden + @south_asians_for_biden, and catch our Q+A with Girls Who Code founder @reshmasaujani at the start of our webinar. RSVP here.

Combining compelling storytelling skills and a sociological lens of qualitative research, Girls Who Code co-founder Reshma Saujani provides a manual for women of all ages (and the men in their lives) on how to leave the pursuit of perfection behind for what she calls the “bravery mindset.” With the help of hundreds of interviews with girls and women from across the country, Saujani breaks down complex issues like childhood conditioning and systemic influences on the psyche of a girl, ultimately teaching her to believe that her worth is dependent on the ability to be perfect, likable and successful. In the current wave of feminism, girls are being reminded to be bold, take risks and pursue the same lives as their male peers. At the same time, outdated cultural norms have not been reassessed. In “Brave, Not Perfect” Saujani notes:

[Girls] have to be nice, but also fierce; polite, but also bold; cooperative but trailblazing; strong but also pretty. All this plus, in a culture that lauds effortless perfection, making it look like they are not trying a bit.

This “perfect girl” messaging wires unrealistic expectations and crushing pressure in girls, which turns into risk-aversion in their professional, academic and personal lives as adults. The role conflicts experienced by women have also contributed to escalating depression and anxiety rates. “Brave, Not Perfect” spells out Saujani’s plan for how this code can be revised and rewritten to bring the power back.

The timing of this book is especially poignant. With the COVID-19 global pandemic, now more than ever, girls and women are experiencing setbacks in the workforce, academia and at home with family members and partners. “Brave, Not Perfect” provides a necessary reminder that these setbacks are part of the human experience, and not an existential declaration of anyone’s purpose, ability and esteem (or lack thereof). Saujani’s book provides her readers with an opportunity to reflect on their own setbacks, rejections and failures, and be brave as they move forward with these lessons. Beyond embracing failure, Saujani guides her readers on tangible ways to say no and remove the habit of “people-pleasing” by often referencing the #MeToo movement. As readers quarantine, this book may help distinguish which acts of empathy are draining versus those that are healing, including prioritizing self-health and aligning actions with a life purpose.

[Read Related: Book Review and Interview: ‘Well-Behaved Indian Women’ by Saumya Dave]

The beauty of “Brave, Not Perfect” is that although it can be read like a self-help book, the manual-like structure urges readers to actively engage with the content. The bulleted sections, internal dialogues, variety of stories, discussion questions and index of terms bring the words alive. Readers can flip to specific exercises, such as ones that can help them unlearn damaging thoughts and empower themselves to be brave. It is an equally good read for the busy 45-year-old mother after a long day of work, for the 24-year-old riding the metro on her way home and for everyone in between. All in all, Saujani did a stunning job in relating to her readers and providing an understanding ear.

Additionally, Saujani beautifully calls out her fellow women peers in no-bullshit terms. She reveals deeply rooted insecurities and misunderstandings about our relationships with others. Despite the structural issues of living in a gendered society that forces women to chase perfection, Saujani claims a few of our responsibilities in this process—like, the need to improve our ability to receive critical feedback and support fellow women peers. Difficult situations arise that test these skills, and by using our “bravery muscles,” we are acting in resistance to eliminate our obsession with perfection.

Another special aspect of the book is Saujani’s reflection on setbacks and acts of bravery that occurred specifically due to her Indian heritage. Depending on culture, perfection may vary greatly and certain acts of bravery may not be as welcomed. As a South Asian woman myself, it will be interesting to see tools specific to the South Asian experience. For instance, family, honor and shame, and of course, our favorite reminder of family reputation, Log Kya Kahenge, adds levels to this discourse. As cultures dilute in diverse societies, it could be helpful to see acts of bravery in our South Asian history, culture and religion. These examples may unite generations and close cultural gaps in understanding the eternal and unifying power of women.

On a similar note, we cannot have a feminist discourse without mentioning intersectionality, coined by civil rights attorney Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw and studied extensively by the first Black president of the American Sociological Association, Dr. Patricia Hill Collins. Intersectionality emphasizes the oppression and discrimination faced by individuals with various social identities. Acts of bravery look differently for different women, and certain acts of bravery may have detrimental consequences for a Black or brown woman, thus justifying our anxieties.

[Read Related: Book Review and Author Insights: ‘The Impact Mind’ by Fareeha Mahmood]

There is a general critique of feminist literature highlighting feminist thinkers who may have pushed the needle for just a certain few types of women, but who exclude most other women, including women of color, immigrant women, incarcerated women, LGBTQIA+ women, and poor women. Despite mentioning a few influential intersectional feminist thinkers and the good intentions of Saujani’s work, her mentions of Secretary Hillary Clinton, Caitlyn Jenner, and Winston Churchill are questionable. This critique may inspire writers to dive into bravery and perfection from multiple lenses, beyond a neoliberal feminist lens.

Alas—we tend to be more critical (and loving) of those who are closest to us in identity. As a brown woman, I have heightened expectations of another brown woman, especially one like Saujani, who is an extremely influential role model to me. Saujani’s program, Girls who Code, has reached up to 500 million people worldwide. (You go girl! Keep it up. Thank you for this empowering piece of literature and for modeling bravery so well). As Saujani reminds us, we have to look out for each other, critique lovingly and “post up” for the fall-out when a sister takes a risk important for her growth. You know she will do the same for you.

Well, Reshma, I read your book, I took your advice. I am building my own furniture, albeit with, a lot of frustration (and self-growth, if I have to admit). I also am writing more freely and honestly, thanks to you. If I learned anything from your book, it’s, what have I got to lose?

Bravery is a pursuit that adds to your life everything perfection once threatened to take away: authentic joy; a sense of genuine accomplishment; ownership of your fears and the grit to face them down; an openness to new adventures and possibilities; acceptance of all the mistakes, gaffes, flubs and flaws that make you interesting, and that make your life uniquely yours.