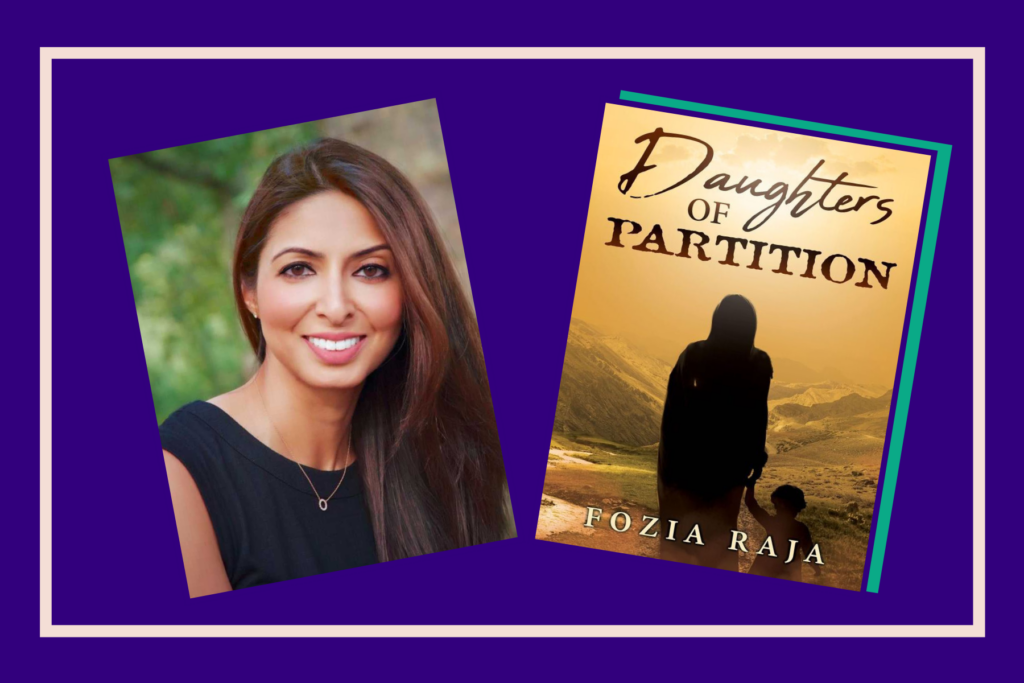

Depicting the heartrending experiences of her own grandmother during partition, Fozia Raja’s “Daughters of Partition” has much to teach us about the power of healing wounds as well as the beautiful outcome of understanding and preserving these legacies.

The story follows Taji Kaur, a young Sikh girl whose blissful life in Lahore and Mirpur is torn to shreds in August 1947. Two years earlier, she marries into an ideal, peaceful lifestyle filled with love and servants (who make her life painfully easy) as she moves from one wealthy, beautiful home to another.

Taji is typical of her contemporaries but also possesses an inexplicable pull towards befriending and caring for her lower-caste, Muslim servants — much to the annoyance and confusion of her mother-in-law — although even their relationship is underlaid with love, unlike the typical animosity of mothers-in-law towards sons’ brides.

[Read Related: Books and Borders: a Tamil Migrant About Life in the Sri Lankan Civil War]

All this is snatched away in an instant when partition is declared and an eight-month pregnant Taji, husband Gurpul and their young daughter Rajendar, are forced to leave their Mirpur home and embark on a slow, taxing march by foot, towards India.

Unspeakable horrors ensue, transforming a somewhat slow-moving, rose-tinted story, into something cruel and bleak. This shift is compelling and heartbreaking yet entirely unsurprising to anyone who understands the Indo-Pak partition.

Though the injustice and unprovoked violence Taji endures in the second half of the novel only takes place over the course of a few days, it is a life-changing moment. She must take on a new name, religion, standard of living, and eventually, another country to call home. For 30 years, her family believes she is dead until unlikely circumstances allow them to re-connect.

I only wish, perhaps, to have heard more about Taji’s life after partition — the woman she became and how she rebuilt herself through another migration, as opposed to so much time dwelt on her coming of age during innocent days when she is blissfully apolitical and treats conversation about the British or Independence with disdain and boredom. Although it presents a nice contrast with how political events later infringe on her in unimaginable and irreversible ways.

But the fact is, the novel remains apolitical. Never is the prospect or potential joy of Independence mentioned, nor are we brought to think in-depth about the reasons behind the hatred. Violence, fear and hunger appear randomly and contextless (foreshadowed only lightly, by increased intensity of political discussion and rumours of killings — a slow-creeping shadow of tragedy as days of Empire draw to a close) in the lives of Taji and her contemporaries. The devastation of partition was felt upon small lives when the sudden moving of borders left them carelessly exiled overnight in their beloved homelands, with minute, forgotten consequences.

Many of our grandparents have similar stories to share — practically every Punjabi family does — it’s a blurry legacy looming in our not-too-distant collective memory. For many, these are still too raw, heartbreaking and shameful to be told freely. Too much was given up and left behind for internal wounds to have fully healed, even all these years later.

Many partition stories remain deeply buried within the fabric of our older generations. Taji Kaur was different. She told her story and discussed her past life proudly with her family in England and wished for the rest of the world to hear what she and so many women went through.

The story of India’s abducted Hindu and Sikh women has been manipulated by those in power to represent a victimised nation, stunted and destroyed by a young Pakistan. Taji’s narrative powerfully subverts this, to tell of pain, bewilderment and cruelty on all religious sides.

Where Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs lived in relative harmony in Taji’s rosy youth, all turned on one another, and have continued to do so, in equal measure. We see both nuance and goodness within her abductors. Through the voice of her granddaughter, Taji, the abducted woman, wrests back power to tell her own story and define what it meant.

“Daughters of Partition” is a strong message about the power of letting go of wounds caused by the events of 1947; to see the humanity behind the numbers and its impact, particularly upon the subcontinents’ daughters, wives, sisters and mothers — of all religions.

[Read Related: Struggling to Communicate With my Indian Mother in her Language? So am I as her Daughter!]

How many daughters were birthed not only by partition but also prevailing doctrines of shame and honour that prevented these women from reuniting with families? How many forgotten worlds and pasts will we never know, if we fail to speak with elders about lives once had? “Daughters of Partition” gives us a glimpse into just one of those countless windows.

The novel is not only about strength and resilience in the face of adversity but also the beautiful outcome of talking and sharing. After having spent two years interviewing her grandmother, Raja shows an exercise in passing down and preserving oral history through her work — of generations working together to understand and humanise one another, despite growing up worlds apart.

Through listening to experiences, we begin to unpick and unravel legacies of hatred from nearly a century ago that still live on today, here in Britain. An unsettling, painful story but one we must not shy away from.