“The diaspora can be, on one level, a direct result of the migrations after Partition.” — Aanchal Malhotra

The things we carry: exploring the memories of Partition through personal belongings.

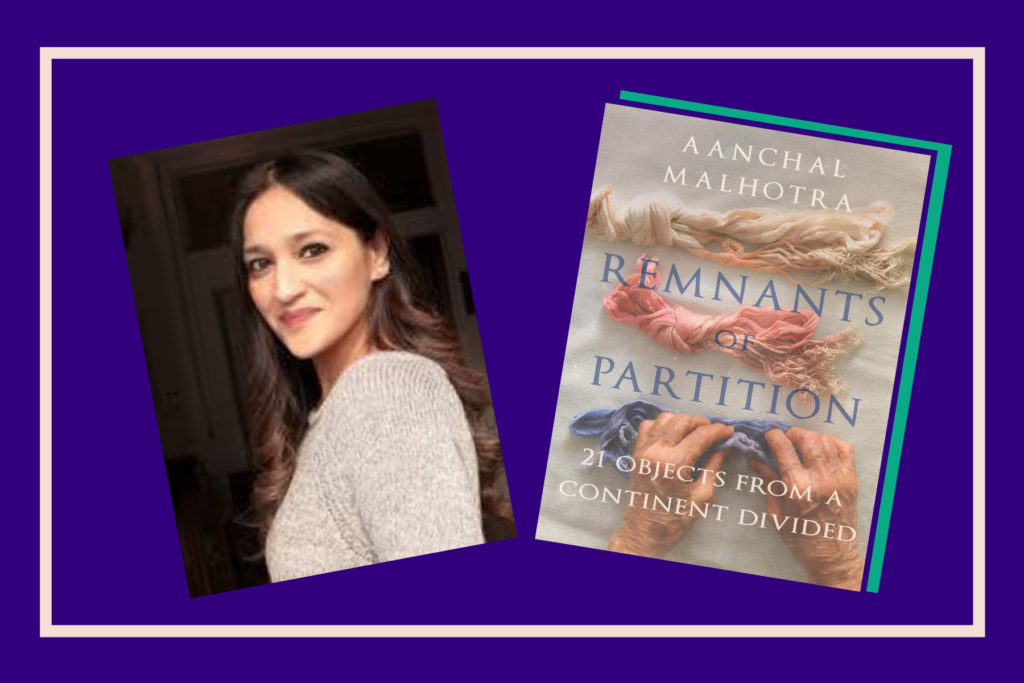

“Remnants of Partition: 21 Objects from a Continent Divided,” by Aanchal Malhotra, is a collection of 21 interviews that are centered around physical objects that refugees and migrants took with them when they left their homes during the Partition. At once purposeful but unhurried, she writes with a gentle and respectful curiosity about the stories she has been tasked to keep. These stories aren’t just recounting events in chronological order, but instead are an exploration of the memories of one of the most traumatic and complex events in human history. Objects, especially those associated with memories, develop a tenderness; they become physical containers of our emotions.

View this post on Instagram

Through them, Malhotra softly teases out the human experience of that time. She uses the object as an entryway into stories of family, loss, the journey across the border and most importantly, the memories people kept of their homeland. Malhotra is an observer, a narrator of sorts, and the storytellers are the people with whom she is talking to – peoples whose voices encompass a true reflection of that time. These are the untold stories of Hindu, Muslim, Sikh, men and women; people who fled, as migrants or refugees during and immediately after the Partition.

The objects are a variety of things. There are stories of mundane household items like spoons and plates, and sentimental family items like a shawl (baagh) or wedding jewelry. Some stories are anchored on ominous items that were carried for survival, like small knives and large swords, hinting at the violence of that time. Other stories, about valuable jewels and silverware carried for their monetary value, highlight the financial precariousness of that time. Malhotra’s training in the fine arts shines in the vivid descriptions that bring the reader into the room with her: the way the patterns of the rugs in the room were reminiscent of India, the way the sunlight spilled in through the windows, the way a dupatta is draped on one’s head, what the rooms smelled like, what the air felt like.

View this post on Instagram

“I want my generation to know about this in this way, the way that it happened. Not in some RSS or Islamic extremist way, but the way that it happened. How people who lived through it wanted to tell their stories,” Malhotra said.

What began as a conversation with Malhotra’s own grandfather and grand-uncle about their experiences and what their family carried during Partition, grew to become her MFA thesis project. Originally, it was exhibited in visual form as a re-telling of Partition through material objects at Concordia University in Montreal. Eventually, her research was published as a full, non-fiction book. In order to seek interviews, she relied on word of mouth through her community. The criteria included having lived through the Partition and having an accompanying object that crossed borders. In Pakistan, a year after the project began, she worked with the Citizen Archive of Pakistan to get a list of contacts that possibly fit this criterion. I was very curious, as a Pakistani, to learn about her experience there—partly due to my internalized colonial ideas of our differences, and partly a reflection of the current relationship between the two countries. In Pakistan, she met people who hadn’t met any Indians since the Partition, so they were amazed to hear that an Indian from India had come to speak to them. “Yeh mujhse milne ayee hai..India se! (She’s come to see me, from India!)”, she recalls hearing often in Pakistan. She shared that maintaining neutrality was very important, especially when listening to stories from the “other” i.e a Pakistani, or an Indian Muslim. This desire reflects in her writing, it is truly borderless — devoid of any judgment or nationalist sentiment for either side.

[Read Related: ‘Daughters of Partition’: British-Asian Author Fozia Raja’s Journey of Healing Wounds and Preserving Legacies]

The popular narratives about Partition in the media, on both sides of the border, is a one-sided, reductionist telling of a complex, nuanced and expansive event. From the very first page, in the preface, Malhotra sets the tone: neutral in politics, heavy with humility, curious and reflective of the universal experiences of loss, grief, love, and war. The pages are full of nostalgia and wistful longings of a homeland that lay on the other side of an artificial border. The stories are written with a familiarity and warmth that she herself exudes, the writing just an extension of her. What struck me most about these stories is that although they are about a dark and tragic time, they still have space for optimism and affection. The storytellers speak of their time in their homeland, of their neighbours, of their childhoods with so much delicate love. That is the most powerful and astonishing thing in this trauma: that so much violence and horror cannot take away the depth of love that someone carries in their hearts.

“This knowledge will be lost over subsequent generations, and what we will learn won’t just be second-hand hate and prejudice but an almost mythical construction of what the other is,” Malhotra said.

Partition matters because it still has lingering effects, even if you have never been to the subcontinent and were born as part of the diaspora. We are only three generations removed from it. Those displaced by Partition have often lived entire lifetimes without talking about what happened, as one of the storyteller shares, “there was little talk to the Partition in our house …they made a conscious decision to look forward, always to the future.” The silence and shame around enduring the Partition has embedded the trauma within the very seams of our cultural consciousness. In its silence, it has become an enduring force that affects our life choices. It is most pronounced in the family dynamics and conflict due to intercultural or interreligious marriages amongst Indians, Pakistanis, and Bangladeshis. As a therapist, I am aware of the impact of the intergenerational trauma of Partition on our grandparents, our parents and subsequently on us. With works like this, the hope is to lift the veil of silence and loneliness our grandparents and parents have held on to for decades. I hope that borderless art like “Remnants” continues to move us closer to each other despite the bloody history.

[Read Related: “Cracking India” to “Earth” — A Look at the India/Pakistan Partition Onscreen]

“Remnants” is an audacious effort to highlight our similarities and our desire to be connected to each other, regardless of the arbitrary Radcliffe line drawn in the sand. It gives language and context to an event that is silently present in every Indian, Bangladeshi and Pakistani household around the world. The stories validate anyone who has ever wondered about their roots. As a Pakistani married to an Indian myself, it made me think about identity within our home and what that means for us. It encouraged me to take a look at myself and my family, to trace my parents’ journey and simultaneously mine. We have all lived exquisite and remarkable pasts. That is the powerful core of the book: each of us contains a multitude of stories and generational experiences that shape us today.

This is a quietly powerful book; poignant, delicate and reflective. It is an alternative telling of the history of the Partition as a meditation on identity, belonging, and home. It doesn’t seek to answer any questions or allocate accountability; the sole purpose these stories serve is to share the experiences of everyday people who were deeply impacted by Partition. Now, more than ever, with the tensions rising between the two countries — it is imperative that we remember our past. Not only remember it but prevent it from happening again — the lawless, mindless violence based on perceived differences. Malhotra’s mission to record this history and help one understand the ‘other’ is, by proxy, also a mission to create empathy between individuals. In the current political landscape on both sides of the border, it’s heartwarming to see a voice aiming to unite us. Something Malhotra said in our conversation has stayed with me, about the lasting power of stories and memories of Partition:

“Anything that involves the prism of human memory, will always be cavernous. There will always be more to explore and discover. There won’t come a time when we won’t find more information about it, it will always have some form of resonance — it will never die,” Malhotra said.

Malhotra is an oral historian and author of “Remnants of Partition: 21 Objects from a Continent Divided” (Hurst Publishers, 2019). She is also a co-founder of The Museum of Material Memory, a digital repository tracing family histories and social ethnography through heirlooms, collectibles and antiques from the Indian subcontinent. Her next book, a non-fiction work on the generational impact of Partition, titled “In the Language of Remembering,” is slated to be published in 2021. After that, in 2022, her novel about World War One will be published.

Follow Aanchal Malhotra on Instagram and buy your copy of “Remnants!”