Right before the pandemic hit, I took a class that coincidentally imbued upon me notions of environmental feminism and queer ecologies. I started meditating more deeply on the porosity between the Earth Goddess and our bodies—namely, how we belong to Her even though so much of our society is built around the assumption that She (can) belong to us. Anjali Enjeti’s “The Parted Earth” problematizes this idea specifically within the context of 1947 Partition. In doing so, Enjeti delves into some of my most favorite themes including belonging, time, memory, nostalgia and intergenerational healing.

Right before diving into “The Parted Earth,” I heard about the concept of “rematriation” during an International Womxn’s Day event focused on indigenous thought. Rematriation, the return of someone to earth—as well as repatriation, the return of someone to their country of origin—are both concepts of relevance to Enjeti’s novel. In my life, I have learned that the notion of returning to any past can be awfully romanticized and nearly impossible. The main character in the novel, Deepa, embodies how emotional memory becomes etched into ourselves and can continue to plague us as people and therefore generations.

“The Parted Earth” mirrors fragmentation by being divided into three parts that at first glance appear incongruent—which may be Enjeti’s objective. Some chapters in the book are labeled with dates and locations while others aren’t. And these dates and locations journey in circular and indirect ways, back and forth across time and place. This ambiguity mirrors the ebb-and-flow of passing time and migrating people, especially when land and people repeatedly break apart. In order for the reader to reach an understanding of the story’s continuity, Enjeti draws you in primarily through character development and scene description. I was thoroughly committed and felt deeply connected to each one of the characters who parallel each other in action and thought. Since personhood and humxnity are of importance to me, this book is something I would recommend over and over again, to anyone and everyone, but especially to South Asians who have a direct connection to Partition. This story won’t heal you, but it will give you a band to firmly hold onto to feel unfractured.

[Read Related: ‘Daughters of Partition’: British-Asian Author Fozia Raja’s Journey of Healing Wounds and Preserving Legacies]

Enjeti’s novel unsurprisingly has a lot to do with emotion. So brace yourself. Many of the characters in the novel embody how feelings and memories can be buried deep into us, especially during times of trauma. This had me wondering if feelings and memories can also be buried under lands and what this means for the entire region of South Asia. I appreciate that Enjeti’s novel allowed me to think in these nuanced ways. I don’t know if these wonderings will ever be answered in my lifetime, but I do know this novel was beautiful to read.

In Part I, I found myself deeply moved by the romantic, sensual and sexual interactions between the protagonist, Deepa, and her lover, Amir. As their names may suggest, Deepa’s Hindu identity anchors her to Delhi whereas Amir’s Muslim identity pulls (and pushes) his family to Lahore while the earth they fell in love on agitatively partitions. Although much of the dialogue found in Part I didn’t speak directly to my linguistic background, I appreciate how Enjeti narrates the scenes in ways that transport me back to my earliest memories of India: Mogra flowers, sweet shops smelling of coconut and sugar, tiffins, money plants, capsicum, talcum powder, star-fruits, mangoes, and guavas…

Small, small details like these become reminders to the reader that even when the earth breaks, she continues to provide and embody beauty. Enjeti’s commitment to providing sensorial and textural details undoubtedly captured and sustained my buy-in to Deepa’s life which ultimately takes tragic turns.

[Read Related: Book Review: ‘Remnants of Partition: 21 Objects from a Continent Divided’ by Aanchal Malhotra]

Deepa is suddenly forced to leave Delhi and leaves her chances of ever reuniting with Amir who promises to return for their marriage which they’ve already consummated. In leaving Delhi, Deepa also leaves the land that she feels the most attached to. Whereas Amir leaves the love of his life. Place and place-breaking congeal with person and person-breaking. This is evidently what Partition was: the trauma that earth absorbed in 1947.

While Enjeti’s novel gives us the chance to reckon with the past, she also shows how past traumas permutate into grief, regret, shame, guilt and erasure—engendering exponential trauma. The part of the book that drew me in the most is how Deepa grows into becoming a “prickly woman,” specifically a prickly grandmother, to another main character, Shan(ti).

Part II begins with Shanti (who goes by “Shan” for most of her life) traveling to see the Taj Mahal with her father. Her push-and-pull relationship with her father, Vijay, illustrates how trauma is passed down through generations—even as descendants genetically mix and become more multicultural in the process. Enjeti herself has multiple cultures she belongs to which makes me wonder if people belong to cultures or if cultures belong to people—or if we all just belong to an earth that continues to break as borders continue to be arbitrarily constructed around, above and inside of us.

I come from a very diasporic U.S. identity—what some would even call “hella Californian”—which I lament on all accounts. But with that said, as more western characters (like Shan) get introduced to the story, I identified closer and closer to the dialogue in the novel—which is something I had to reckon with: my own insularity. While Shan adopts this assimilation-friendly name, countless life events lead her to want to return back to her origin story. She simply wants to belong. Accessing the financial privilege that her life as a lawyer allows, she is able to trace her roots and return to the parts of her that feel most lost, which she does in the final part, Part III.

[Read Related: Partition Drew a Line Between us and we Dared to Cross it]

But returning doesn’t truly exist. I personally am (stupidly) on a lifelong search to define Belonging: do we belong to a place, does a place belong to us, are our belongings whatever we carry with us, are our bodies our only belongings, is belonging imagined because we anyways belong to the Earth Goddess? Enjeti lets me ponder these questions and I thank her for that.

Not being able to answer these questions in direct and lucid ways can form bitterness, which is exactly what Deepa harbors for the vast majority of the novel. But by the end, she doesn’t. This is my main takeaway. Shan’s homecoming journey allows for both she and Deepa to release themselves from the cycle of grief and move towards joy. And if grief and joy are emotions that are part of a cyclical duality, the end of the novel at least allows them to swing away from grief and swing towards joy.

In addition to being a (shitty by default) U.S. citizen, I am also the grandchild of late Partition survivors. So this novel necessarily spoke to me, and the obsession with longing and archiving that I invariably inherited from my family and ancestors. We deserve to know ourselves. Yet archiving is messy, circular and indirect, as Enjeti’s novel shows.

There are many moments during the novel that Enjeti ridicules with the aim of critiquing western obsession with clinical sterility, and I would argue that archiving Partition stories—when done well—should be anything but sterile. Learning about fucked up shit necessarily means stirring fucked up shit that may have cemented over time. And I applaud Enjeti for doing this work, of confronting the ghosts that live around and inside of us, by way of her novel.

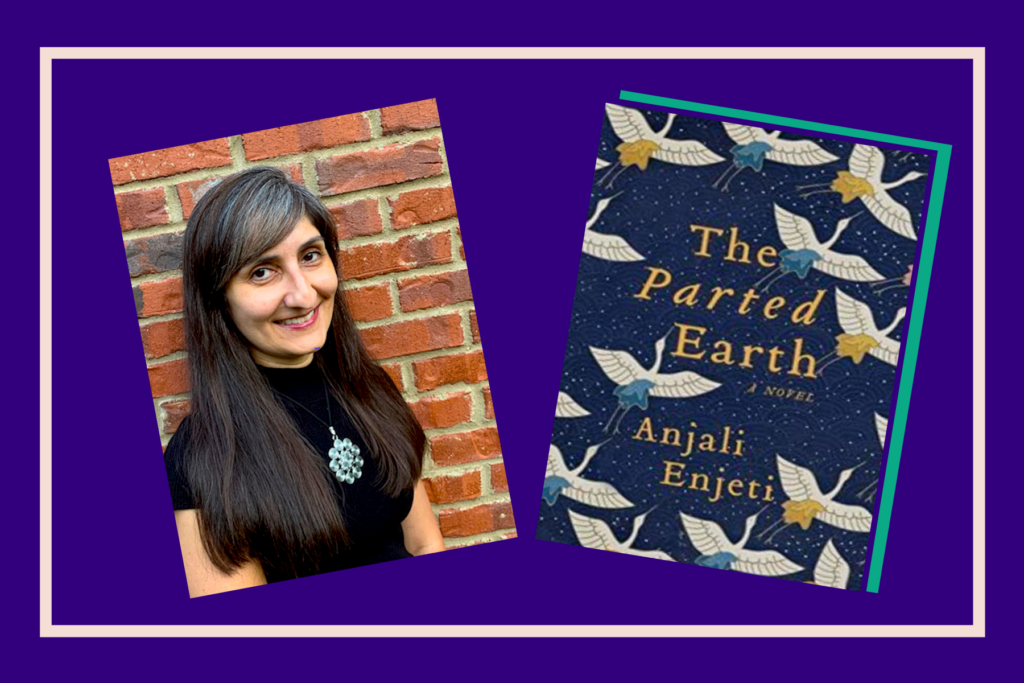

This spring, Anjali Enjeti plans to publish her first two books. “The Parted Earth” is set to release in early May whereas “Southbound” is set to release earlier, in April. “Southbound” is a collection of academically-cited essays whereas “The Parted Earth” reads like a ficto-critical novel that I chose to dive into first. Borrowing from the word Partition, “The Parted Earth” is a book about memory and how memories are stored in our bodies and the collective body of South Asia.

To learn more about Enjeti’s book and where to purchase them, visit her website.