Despite almost definitive perceptions of the forbiddance of permanent tattoos in Islam, a snapshot, both historical and contemporary, of Muslims throughout the world convey a very different story from the monolithic narrative that is often adopted.

In terms of religious posturing, it is important to outline exactly where scripture falls on this issue and how different conclusions and consequent religious authority (or lack thereof) have developed accordingly. Sunni Islam falls decidedly on the line of prohibiting tattoos, as based on Qur’anic scripture and Hadiths, however, converts with pre-existing tattoos are generally not regarded as having broken the religious prohibition. In terms of the Qur’an, Chapter 4: Verses 117-120 provide the basis of Sunni understanding that tattoos are forbidden as they constitute changing the creation of God.

If you wash your hands, grab your nearest Qur’an, and turn to these verses, you will find something curious: the language is a bit more nebulous than anything that could possibly give way to a hard line religious conclusion. Instead, the verses reference the determination of the Shaitaan (Satan) to lead believers astray by, among other things, encouraging the alteration of God’s creation. Thus, the act of tattooing the body is synonymous with an action guided by evil, in terms of Sunni religious analysis.

With respect to Hadiths, the Sunni ban of tattoos finds more sure footing as there are narrations of the Prophet Muhammad (saw) outwardly condemning tattoos and those who give them per Bukhari. As a residual issue, there is also a long-standing belief that tattoos prevent proper wudu (cleansing for spiritual and physical hygiene). However, given that tattoos are completely permeable, there is nothing about tattoos which prevent the skin from being cleansed and, thus, invalidating the purification process. Whether or not the content of one’s tattoos—images or words—could invalidate wudu, however, is another inquiry altogether.

The Shi’a tradition, on the other hand, is largely critical of the authenticity of hadiths thus granting the narrations with less reverence than that granted by Sunnis. However, because of the pervasive anti-Shi’a sentiment that stems from Sunni supremacy within the global Muslim community, permanent tattoos, while not forbidden, are strongly disfavored and looked down upon by Shi’a scholars because of the underlying desire to fall more in line with Sunni traditions and thereby lessen the gravity of anti-Shi’a discrimination. Nonetheless, some Shi’a communities’ standing traditions of religious tattoos feature various Shi’a symbols and illustrations of Imams.

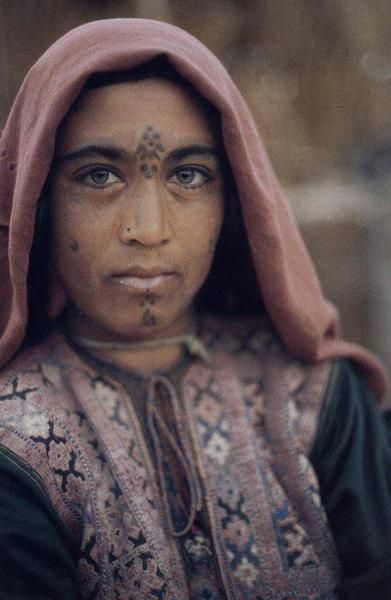

Despite these various religious decrees surrounding tattoos, Muslims—both Sunni and Shi’a—have adorned themselves with tattoos of cultural display for centuries. Pathans of central and south Asia are known for tattooing themselves with Sheen Kaal, or etchings to deflect the evil eye. Often times these tattoos would be placed on their faces as prime anatomical real estate for guarding against dark energy.

[Pathan woman with Sheen Kaal tattoos on her face/Photo source: Pinterest]

[Pathan woman with Sheen Kaal tattoos on her face/Photo source: Pinterest]

In Algeria’s Aures Mountains, there resides a tribe in which the women have elaborate facial tattoos in accordance with pre-Islamic cultural traditions. Under this tradition, the tattoos serve as both methods of beautification and healing. With growing literacy in these once secluded rural spaces, however, the tradition of facial tattoos in these Algerian tribes is waning as their populations learn that tattoos are doctrinally forbidden in Sunni Islam.

[Algerian woman with traditional facial tattoos/Photo source: Pinterest]

[Algerian woman with traditional facial tattoos/Photo source: Pinterest]

Outside of longstanding tattoo traditions among Muslim communities in certain pockets of the world, more and more Muslims without such cultural predispositions have started taking ink to skin. In October 2016, Huck Magazine published a feature piece on Kendyl Noor Aurora, a fully tattooed hijab sporting Muslim woman. Although Aurora got most of her tattoos before she converted to Islam, the feature piece revealed that she viewed her tattoos as visual representations of her love and devotion to God—just like her hijab.

Aurora is not alone in this belief. Many tattooed Muslims do not believe that their tattoos serve as any kind of hindrance to their faith and, similarly, do not believe that they are any less Muslim for having them.

In fact, here are a few Muslims, who speak about their favorite ink and decision to get tattooed as weighed with their Islamic faith.

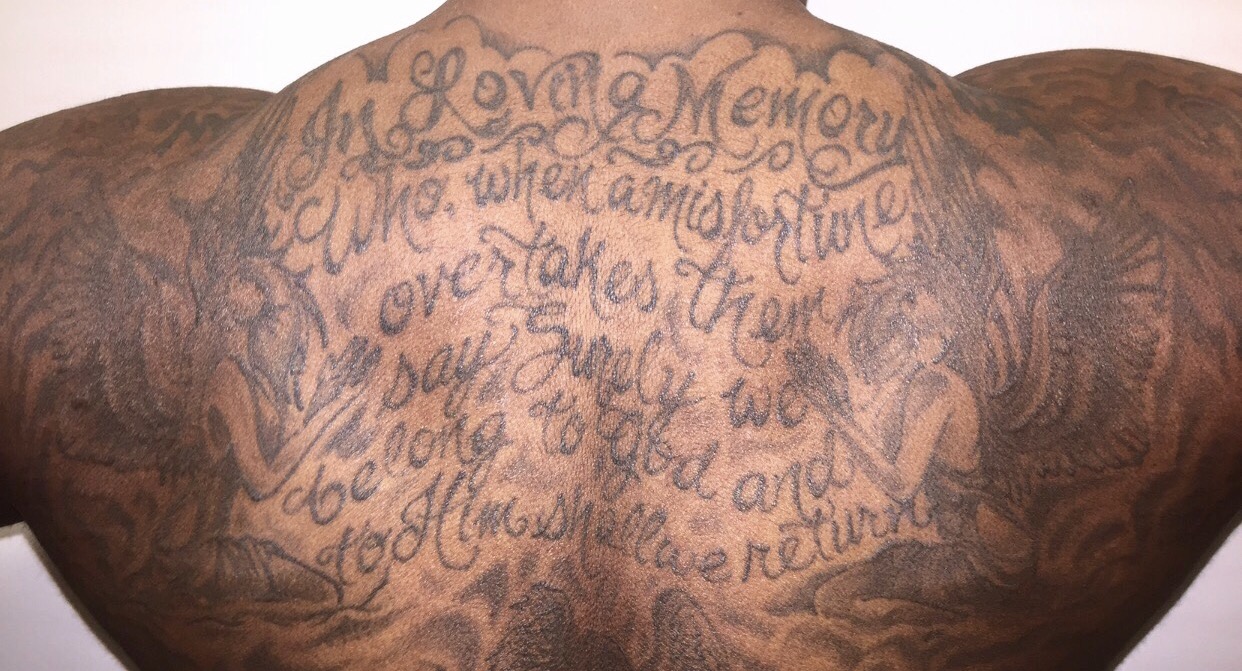

[Azam’s tattoos/Photo published with permission]

[Azam’s tattoos/Photo published with permission]

“Behind almost every tattoo is a story and mine is no different. To some people, tattooing is an extreme action, but to others, tattoos offer peace in knowing that one’s story will always be with them, forever on their skin. My most significant tattoo takes up my entire back and is dedicated to my late grandfather Mohammed Khalleel.

While growing up in New York, I was lost and was rapidly heading down a path of destruction, to a point of no return, to a life in prison or just another dead person on a New York street. I was a product of my environment, poisoning everything in my path. It was as though I was in quicksand, sinking deeper and deeper until my grandfather offered to have me live with him and my grandmother in Florida while I completed high school.

My grandfather was exactly what a good Muslim should be: he knew exactly who I was and he never judged or treated me differently. Instead, he chose to welcome a troubled kid into his home and help him not only find himself but become a responsible man in the process. Living with my grandparents changed my life. My grandfather never had a son, so I became the one he never had.

On December 11, 2011, my grandfather passed away and I was devastated. On the day of his funeral, I went down to the bottom of his grave, received his body and lay him to rest gracefully and with pride. Since then, I have tried to live up to the man he wanted me to be.

I am currently serving in the US ARMY, and I am making my family, friends and colleagues, very proud with all that I do in my life and with how I have been able to turn it all around. I owe all of this to my grandfather. He gave me a second chance at life. This is my story behind my tattoo and why it is part of my life story. The main and largest portion of my tattoo is a verse from Surah al-Baqarah, which reads, ‘Who, when a misfortune overtakes them say, Surely we belong to God and to Him shall we return.'”

[Shaliza’s tattoo/Photo published with permission]

[Shaliza’s tattoo/Photo published with permission]

“My decision to get a tattoo was based on simply feeling comfortable in my own skin and being able to express what I find beautiful on my own body. Having a tattoo doesn’t make me any less Muslim. I pray, I fast during Ramadan, and I don’t let my tattoo make me feel less grounded in my faith. There are Muslims without tattoos who commit far graver acts while pointing fingers at those with ink, which makes very little sense. My favorite tattoo is of a flower on my back. It represents exactly what I have described here—an expression of beauty on my body.”

[Hibah’s tattoos/Photo published with permission]

[Hibah’s tattoos/Photo published with permission]

“I have about 19 tattoos. I got my first tattoo when I was 19-years-old: A tiny heart with a square inside of it, tattooed on the right side of my ribs. It was done very poorly and not in a tattoo shop. It’s not something I show off but I adore the memories behind it.

Tattoos have always intrigued me since I was a teenager. I knew it was something that was not permitted in Islam but I also knew that Muslims have been getting tattooed for centuries. I struggled with the fact that I may be rejected from the Muslim community because of my tattoos but quickly decided that it really doesn’t matter what people think, because at the end of the day, Allah knows what’s is in my heart and knows me best.

As long as I remain faithful to my religion, that’s all that matters. All of my tattoos have special meanings behind them. I’m currently getting work done on a piece that is inspired by geometric Islamic art, located on my left forearm. This piece and my hand/ finger tattoos are the most meaningful tattoos I have. The ones on my hand and fingers are inspired by plants and Mehndi designs. Both are things I love and I also bring these designs into my own art as an artist. So why wouldn’t I put them on my body forever?”

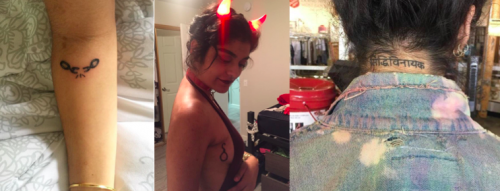

[Suraiya’s tattoos/Photo published with permission]

[Suraiya’s tattoos/Photo published with permission]

“I grew up a Shia-Ismaili Muslim, so my childhood is littered with small glances of half-sleeves and ankle tattoos of the more alternative auntie and uncle population. In general, I never had an issue with body modification, my parents only had slight concerns. My dad actually took me to get my first six piercings throughout my teen years and didn’t bat an eye to dying my hair green. My mother was less sympathetic, of course, but still, they all just sung the “no tattoos or we’ll peel your skin off,” song when I turned 18-years-old.

At 13, my father decorated my room with Ankh’s to help me understand my femininity—I gave myself a tiny stick-n-poke tattoo of one when I was 15. They have yet to notice it, five years later.

My real tattoos didn’t come until I left home and moved to Los Angeles. I come from a home of mixed religious traditions, and my mother has always kept Ganapathi (Hindu Remover of Obstacles) as her de facto patron saint. On my first Jummah in Los Angeles, I went and got ‘Siddivinayaka’ or ‘Long Live Lord Ganesh’ on the back of my neck.

My other tattoos play into my mysticism. The broken chains are for the chains we Shia’s beat ourselves with during Ashura. Even though our pain binds us to this earth, our souls remain unfettered. The noose is for Hazrat Mansur Al-Hallaj, Sufi Saint who was martyred for stating in ambiguity ‘I am the Truth’” I keep the noose he died on close to me, to remind myself that being a mystic makes you an enemy to broader populations–our death is just as guaranteed as our devotion.

My tattoos are expressions and extensions of Islam; direct adornments that heighten my relationship with Allah and Ahl Al-Bayt.

To those who say my tattoos are sins, my response is that it is only through sins that we can create a relationship with divinity. I see God as the purest manifestation of empathy, ink or no ink, and I simply exist to be a devotee to that empathy.”

[Jamin’s tattoos/Photo published with permission]

[Jamin’s tattoos/Photo published with permission]

“I’m a practicing South Asian Muslim with tattoos and piercings, things that aren’t common amongst my peers. When they find out, frightened stares melt into passive aggressive comments. ‘I mean, they’re cool but I would never get one. It’s against the religion.’ I’ve been having this conversation since I was sixteen when piercings and tattoos became both a coping mechanism and form of self-expression. My creative soul wanted to honor my journey through art. The adrenaline rush through the process was a bonus.

Much to my mom’s dismay, I sat under the gun at eighteen to get a small tattoo on my hip, which has transformed into a large piece featuring a lotus, crescent moon, and a representation of the lote tree from the Q’uran with some jewels representing a ring my grandfather wears. The lote-tree, a tree bearing fruit where angels play in Heaven, represents knowledge, but it’s also a tribute to my faith.

My family lives on my shoulder, where they help me bear the load of the world. A lily for Mom and orchids for grandmother, aunt and uncle, surrounded by mendhi designs as a tribute to my South Asian roots, are always with me. These pieces are huge and peak through my clothing. They serve as the label by which my friends in South Asian circles deem me the rebel. I wouldn’t change a thing about how I tell my story or honor my journey.”

[Rashed’s tattoos/Photo published with permission]

[Rashed’s tattoos/Photo published with permission]

“My name is Rashed Alison but many people just call me Rodi. I’m 38 years old and I have been living in Sweden since 1990. I am a tattoo artist and have been tattooing since 2010. I own my own studio—Ink On Skin Tattoo—in Malmö, Sweden. My views about tattooing and religion are quite open. Since I am Shi’a Muslim, it is neither forbidden nor haram for us to tattoo ourselves because we do not believe that it stands in the way of proper wudu (the washing of our face, arms, and feet before prayer). Tattoo ink is inserted underneath the skin and it does not prevent water from cleansing skin during wudu. I know that for Sunni Muslims, however, it is haram to have a tattoo.

I believe that God is the only one who has the right answers, and on the Day of Judgment, God will punish me if I ever did something wrong. As for what people say or think— I do not care so much about that. More important than what is on our skin, I believe that God examines our actions toward others in life and how we treat fellow human beings. I just want to say to everyone: Do what feels right for you and in your heart, and do not worry what others say or think. People always have an opinion about everything, but who cares? If it feels right for you then do it.”

The Muslims featured above represent a large and perpetually growing community of tattooed Muslims who are still firm in their faith and their religious identity. Their tattoos, however, are not a new development in the Muslim community—Muslims have been getting tattooed throughout the world for various purposes, be they cultural or spiritual.

Their stories reveal that they are not as taboo or as rare in the Muslim community as many would believe. In fact, they are slowly becoming more widely done as religious understanding surrounding tattoos continues to adjust.

If you’re Muslim and tattooed, share a pic of your favorite tattoo(s) with us at BG with the hashtag #BGMuslimAndTatted. We would love to feature you here.