The long-lasting treacherous and heart-wrenching effects of the India and Pakistan partition are embedded in the hearts of South Asians everywhere.

Whether it was our grandparents or great-grandparents caught in the midst of British colonial sanctioned segregation, the violent legacy of 1947 and beyond comes with trauma, hegemonic nationalism, hatred, and religious-militaristic state ideologies. India was a quasi-religious thriving world empire before bearing the destruction of imperialism and colonialism; the British’s racist imperial project gave rise to historical tragedy saturated in mass genocide.

Through oral testimonies, published newspaper articles, and eyewitness accounts, we have become acquainted with the stories of our ancestors leaving their homes behind and fleeing. The partition was characterized by the death of thousands of South Asians and the exodus of millions of more refugees uprooted in a vision of uncertainty and loss.

Throughout the Indian subcontinent, communities that once coexisted began to senselessly attack one another, and perhaps the carnage was felt with full intensity in Punjab and Bengal (provinces on what is now Pakistan’s border). Amidst mass abductions, forced conversions, and massacres, some 75 thousand women were raped and disfigured. Between the status of disputed territories and the colossal wave of migration, the stories of individuals are often lost.

Lenny is the daughter of an affluent Parsee family in Lahore, through whom we discover diversity and grand betrayal. The purpose of both the film and the novel was to illustrate women’s experiences during the partition as well as the impact that conflict caused in their lives. While “Cracking India” and “Earth” are both birthed from diasporia interpretations of the partition, the unpacking of events is told in distinct ways.

Through the book we become attached to Lenny’s innocence as she navigates the fringes of Lahore, growing up to bear the implications of conditional violence. The first-person perspective of “Cracking India” details very painful moments only realized through growth.

These elements are, unintentionally, lost in the third person/adult perspective we observe in “Earth.” Lenny narrates the story through the voice of her adult self, recalling uncomfortable and difficult events that shaped the way she understood what 1947 meant. However, through the film, we gain vital visual representations of death, raids, brutal murder, and sheer emotion. Given that our imaginations are limited by a sense of reality, adding faces to characters made the story all the more real. By taking a step back and acknowledging that “Cracking India” and “Earth” are two distinct, but holistic, interpretations of Lenny identifying religious, ethnic, and racial violence, it becomes easier to appreciate stylistic and thematic differences.

In the process of streamlining a novel, films are keen to highlight either violence or romance, as “Earth” sensationalized the hetero-romantic “love triangle” among Ayah, the Ice-Candy Man, and Masseur. “Cracking India” centers on Lenny’s observations and subsequently, what she lost. Lenny, a naïve and curious young girl, is able to eavesdrop on adult conversations, drawing a complete perception of events occurring between several religious groups.

The fact that Lenny is kept out of school because of her disability grants her more time to be consistently surrounded by adults conversing about the burden of partition.

“I was born with an awareness of the war and I recall the dim, faraway fear of bombs that tinged with bitterness my mother’s milk.”

The novel dramatizes impeding confusions experienced by a young girl becoming adjusted to the rules of her community/society as those rules are forcibly reconstructed to fit a new power dynamic. For instance, through Lenny’s innocence, we observe harmonious interactions among Hindus, Muslims, and Sikhs in their group of friends and those who serve the Parsee family before the onset of raids and ethnic cleansing.

An objective relationship between literal and figurative concepts in Sidhwa’s text is emphasized through a child’s decentered agency. Lenny repeatedly struggles to differentiate between the literal and figurative meaning of partition to truly understand its implications. For example, after overhearing multiple discussions about dividing the nation, Lenny ponders how literal partition is materially possible:

“There is much disturbing talk. India is going to be broken. Can one break a country? And what happens if they break it where our house is? Or crack it further up on Warris Road?”

Between Lenny witnessing a child marriage and multiple deaths to her passionate love of Ayah/loss of Ayah and the inevitable loss of innocence that couples the shift throughout the partition, the reader is forced to carry these traumatizing events with them.

Although “Earth” follows the same storyline of a vulnerable Lenny eavesdropping on mature contexts and spending most of her time with Ayah – thus observing the congenial relationship of her Muslim, Hindu, and Sikh suitors – we are not directly connected to her thoughts and feelings and rather more preoccupied with Ayah’s character.

Detailed explanations are instead replaced by vivid imagery.

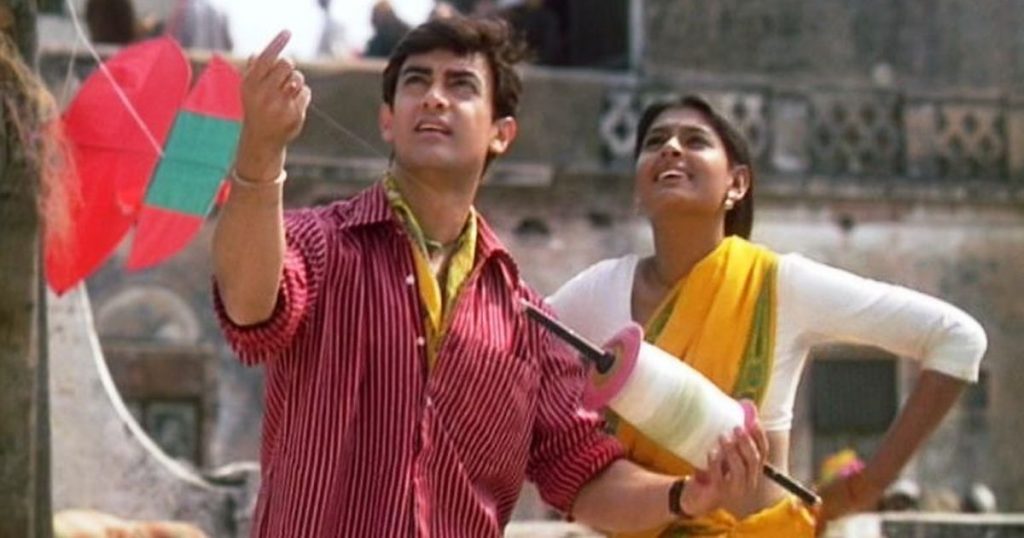

In light of relating to other characters more directly, Mehta highlights a few passionate moments. First, when Ice-Candy man is showing Ayah how to fly a kite as part of a popular festival, coupled with a Bollywood-scene-like song interjection that served as comedic relief.

The second instance is the intense hetero-love scene between Ayah and Masseur that not only made the film cover but is also the probable reason for the film’s popularity. “Earth” seems to indicate that Ice-Candy man’s unwillingness to accept Ayah’s push back and seeing her with Masseur was the reason he abandoned his initial coexisting nature to kill Masseur rather than seeing his dead sister in the train shaft. One can appreciate that unlike the novel, the film depicted Ice-Candy man’s reaction to the train scene, which enhanced the reader’s feelings.

Switching from a wholesome defiance of state violence to a moment of utter devastation concludes a dramatic element. The strategic somber ending is representative of the ongoing hatred amongst Hindus, Muslims, and Sikhs in the Indian subcontinent, as Mehta could have just as easily ended with a hopeful society or happy Ayah.

“Earth” is commendable for not only casting actors who followed the same religion as their characters but also for casting a dark-skinned Indian girl to play Shanta. The main plot that devises a socially affluent Ayah in both “Cracking India” and “Earth” is surprising given that a woman of her class would usually not have free range to spend the majority of her time socializing.

“Cracking India” and “Earth” employ narratives that strip female characters of their agency, render them as victims, or depict them losing something; Lenny and her mother deal with Ayah’s abduction, Ayah ceases will over her own life, and Papoo loses her livelihood as a child.

[Read Related: Reflecting on the Trauma of India and Pakistan’s Partition—70 Years Later]

Closely reading Sidhwa’s book and watching Mehta’s film not only highlights the differences between a first person and third person adult perspective but also illustrates thematic differences in including empowered women. While Sidhwa constructed a vision that revered women as more than just collateral damage, Mehta’s adaptation leaves little to no room for female power. Furthermore, Mehta’s traditional analysis of feminism dictates representation as merely performative and hinders her ability to showcase Sidhwa’s novel apart from the heterosexual nationalist violence.