Artist Symin Adive of ‘Bari: Know Your Place’

In 2018, I conceptualized my first personal project, “Bari: Know Your Place.” Inspired by the high-horizon, miniature style paintings cultivated in Southeast Asia between the 15th and 18th centuries, I wanted to create a series of illustrations and poems that explore the hierarchies of family, class, race, gender, belief, sexuality, and ultimately power through grounded contemporary scenes from my own life as a young, Bangladeshi immigrant as I grew to understand my “place.” For many immigrant artists, their work is a tribute extolling their cultural and familial roots. This instead explores what is to be untethered to the standard ties of family and community as well as the cultural attitudes that led to this break.

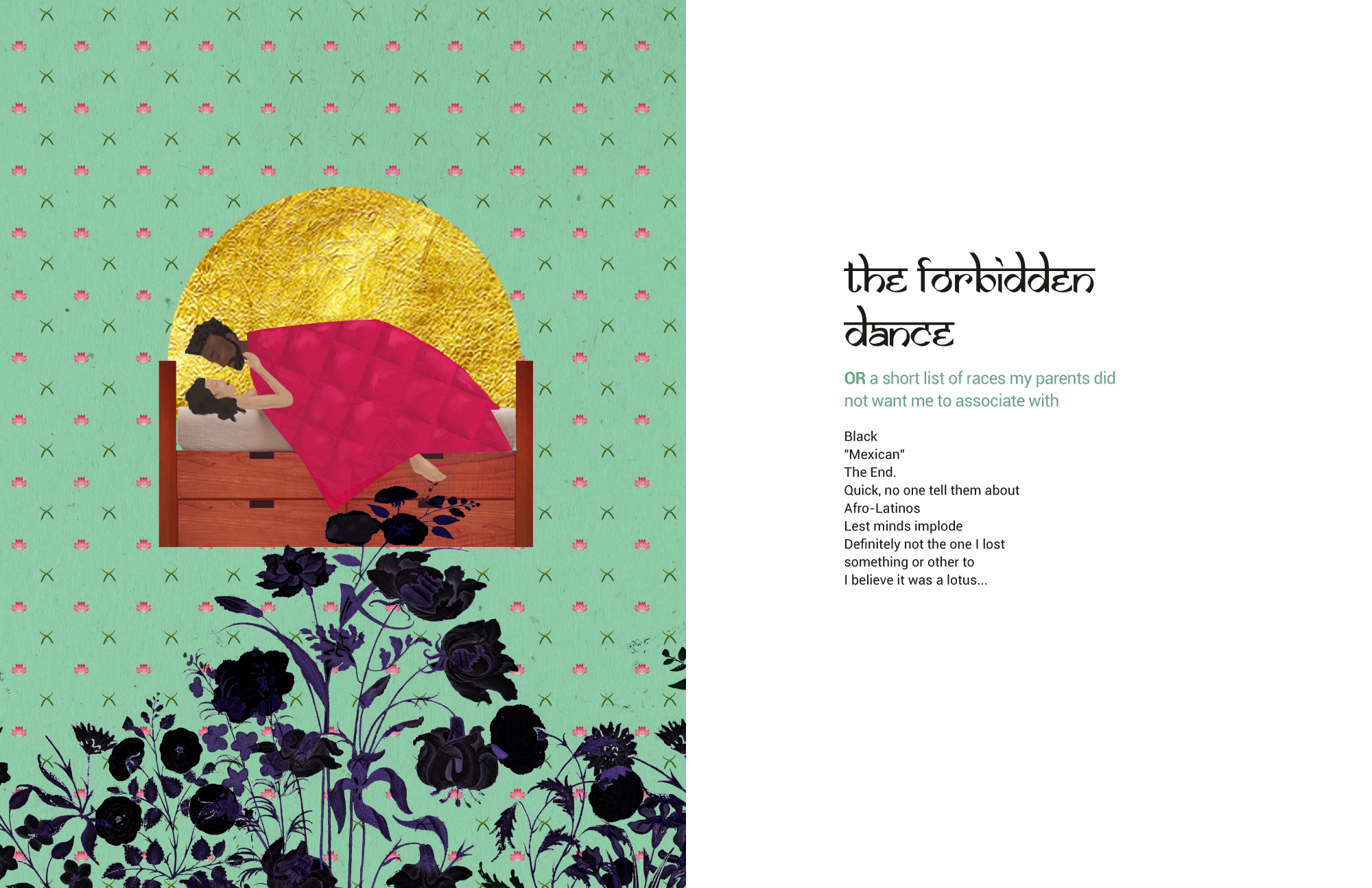

The illustrations in “Bari,” which means home in Bangla, employ the language of these centuries-old storytelling devices that were used to regale the court with tales of the most powerful among them. But here, the pages explicitly and very plainly lay out the kind of stories that have always been encouraged to stay private, realities to be glossed over at best. In complete contrast to much of my previous work, which is grand in scale and inscrutable in style, I wanted to leave nothing up for interpretation here. That’s why every illustration essentially comes with an explanation. I wanted everyone viewing “Bari” to get as up close and personal with me as they could.

This year, I have seen more self-examination of desi culture (especially in regards to its treatment of other POCs) than I’ve ever witnessed before which I’ve found exceedingly heartening. It’s made me think back to this project.

[Read Related: Connecting With the Past and Reclaiming my Identity Using Poetry]

Two out of the 16 stories in “Bari” were about the rejection of the racist attitudes that my family had/has against Black and Latinx people as well as their bias in favor of whiteness. The biases explored here originated within my parents in Bangladesh, in South Asia, before either of them had ever even met a single, Black person but they both made sure to immigrate those prejudices over on to the U.S. along with the whole family. The piece “Greater Than,” which takes place in the late ’90s, was inspired by the need my parents felt to differentiate themselves from other, “lesser” minorities and to elevate their status in the new, All-American pecking order that they now found themselves in; a hierarchy where they would never be at the top of again for as long as they lived in the land of White supremacy.

In the safety of the house and in the car with rolled-up windows, they would try to hammer home this anti-Black and anti-Latin messaging as often as possible. One of these talking points, so to speak, is addressed, in the piece “Forbidden Dance.” We all know that for many South Asian parents the only acceptable interracial coupling is with a White person. That is the only other “approved” option. In their eyes, the others were shameful, dangerous, dirty…

These value judgments, unexamined biases and need to aggressively assert their own power were a big factor in the rift and eventual dissolution of my familial ties. Because of the abusive behavior, I faced throughout my childhood, I never once felt that love, respect or adoration toward my parents that is common even for kids who come from less than ideal homes. I have wondered whether I would have been susceptible to my parent’s irrational, unfounded disparagement of other non-White races had I actually looked at them in the way most people view their parents. After all, my parents were simply parroting racist ideas fed to them by their own families, friends, and culture [with deeply entrenched reverberations of colonialism] that they instinctively loved. You parrot the views of those you grow up loving.

[Read Related: Defining One’s Indo-Caribbean Heritage through Poetry]

So, it can, in a sense, be easier to reject the small-minded belief system of people you don’t care for as I had but what if you grew up loving a racist family and culture? How much of their beliefs had been indoctrinated into you? Do you challenge them now? How much of your thoughts are truly your own?

The entirety of “Bari: Know Your Place” can be found on SyminAdive.com.