We have a lot of intersections. This is the idea that sat with me after closing my mid-June Zoom call with poet Rajiv Mohabir. This is most definitely not a sensation I generally marinate in after most of my other Zoom calls. Talking to Rajiv felt refreshing.

I had heard Rajiv’s powerful words during virtual poetry reading the month prior and I knew we had to connect. I casually messaged him with no expectations in mind, and fortunately, he was oh-so-willing to speak with me.

[Read Related: Nursing the Colonial Hangover Afflicted on my Brown Body]

After thoroughly supporting my quest as an emerging (starving) writer, he enthusiastically shared his insights on how to approach MFA program applications and the literary publishing industry.

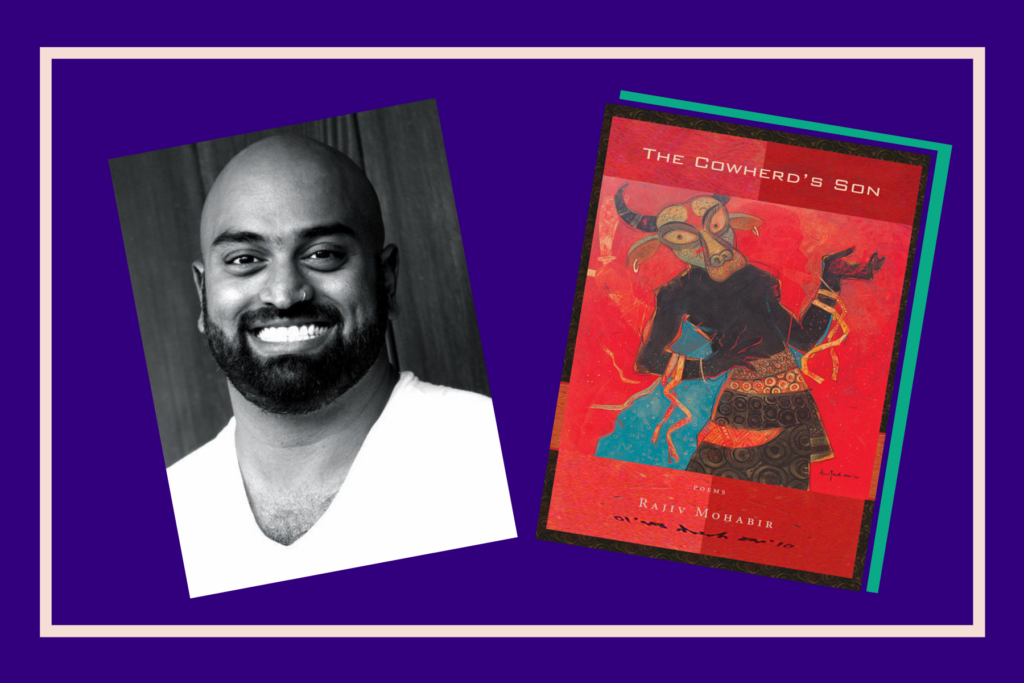

We then agreed that I would review one of his two poetry collections for Brown Girl Magazine. He told me that his first collection, “The Taxidermist’s Cut,” has a “steady darkness” whereas his second collection, “The Cowherd’s Son,” has “both light and darkness.” All things considered, I decided I could use some lightness and humor in my life right about now.

The day I received my copy of “The Cowherd’s Son” in the mail, I excitedly took a selfie with it and sent it to Rajiv.

I steadily sat with this same comfort of our shared intersections as I leafed through the pages of “The Cowherd’s Son.” In the book, Rajiv successfully achieves what we must all commit to doing in our lifetimes: Excavating ourselves to understand the plurality of lives that live within us.

Rajiv’s collection speaks about the porosity between person and place. Rajiv explores these third-spaces by taking us to a variety of geographies where he has lived—in doing so, he takes us to a variety of geographies that now live within him. Although his many selves have moved across multiple places including India, Guyana, Trinidad, New York, Orlando, Toronto and Honolulu, his poetry shows he now embodies these spaces.

on this slate day youths dem

speak no Hindi to know paisa

means money, a taxi speeds by

blaring a chutney remix of

Kaise Bani and you remember

your Aji dropping her rum

at Aunty’s party to jump up

and your mother’s awkward Hindi

-excerpt from “Ode to Richmond Hill”

And after reading Rajiv’s candid, descriptive and brave artwork, I now feel as if these spaces may just almost partially live within me as well.

However, I am not Rajiv. I have identities particular to me: Baluchi, Bhagnari, Kshatriya, queer, desi, partitioned, South-Asian American—to name a few. We have similarities and differences. Namely, indentured servitude and “coolie” history have not directly affected my lived experience (as far as I know). Thus, “The Cowherd’s Son” is equally artistic as it is educational.

He says I’m lucky to be named Paul

because no one will ever suspect

I am brown when I fill out papers

or speak on the phone. Paul is a mask

-excerpt from “My Name is a Map”

Before delving into this collection, I frankly did not know what the title “The Cowherd’s Son” referred to. As I read, I realized the book’s title brings caste to the forefront of the conversation. Centering caste-queerness is essential during a time where the destruction of these intertangled systems of oppression ultimately represents the work we must all be doing.

Reviewing Rajiv’s poetry is like brewing a fresh cup of chai. All his words boil and stew in their pressurized aromatic heat and then I, the reader, filter out the chunks that diffuse these pungent flavors. Interpreting his work is like filtering through heavy bits of cardamom, clove, black pepper, cinnamon sticks, ginger.

the truth is queerness

was a tool for survival, a trade wind to sail a kite

then cut its cotton strings. I imagine

the cane field, the foliage teeth burned

away, blackened, dotted white in strewn

dhotis and pagris of men, inside

men’s mouths and fingers—

-excerpt from “Bound Coolie”

Rajiv queers space, time and memory in this poetry collection by puzzling together the osmosis that takes place between these seemingly-separate categories. In showing that these categories are not separate, but in fact embedded in overlap, Rajiv is able to provide commentary on something we all yearn for: a sense of belonging.

“The Cowherd’s Son” indeed captures both light and darkness through a wide variety of compelling motifs such as salt, sugar, fire, flowers, fruits, recipes, clothing, melodies, waters—and even the lovely Shiv Linga—along with other phallic interpretations of desi culture. So it makes sense the reader deviates along the way in the search of belonging. Rajiv’s poems provide us with the scenic route—which is likely the route that life simply paved for him.

Yet after reading his collection, I am still left with one burning question: Where do his joy and ecstasy truly belong—to a place, to a time period, to a person, to himself? The answer may very well be a complex one.

Logically, queer poetry should not be unidirectional. During the quarantine times of COVID-19, Rajiv’s complex artistry is especially useful for much-needed escapism to gain temporary respite from these current apocalyptic times.

You tell me of a European machine

that removes filth from the Ganga.

If the river removes sin now,

what happens when the massive filters

produce a cleaner water—

-excerpt from “Emptying the Sea”

Pick up this book and lose yourself across the pages, as if you are a ravenous holy cow grazing across international grassy pastures. Satiate your four stomachs and your one palpitating heart with “The Cowherd’s Son.”

[Read Related: Gender Equality Applies to Men, Too]

Pick up a copy of “The Cowherd’s Son” on Amazon and Tupelo Press, and follow Rajiv on Twitter to keep up with his latest literary developments.