“Where are you from?”

Oh, if only you knew what a question you’ve asked, new acquaintance. Normally, asking such a simple question yields an equally simple answer:

“England,”

“India,”

“Korea,”

However, this doesn’t apply to me, or to most of the people I grew up with. My answer is a prologue to my future memoirs:

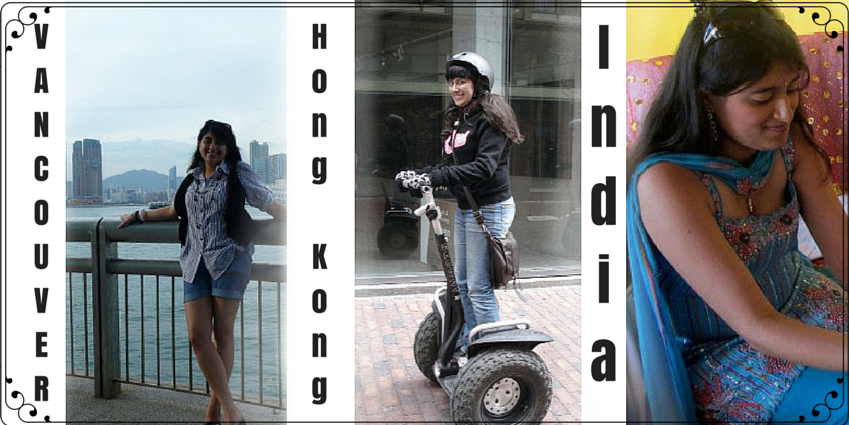

“Well, I’m ethnically Indian, as you can see, but I’m also a Canadian citizen since we fulfilled our five-year residency requirement in Vancouver to become citizens, and a Hong Kong permanent resident since I was born and grew up there. But I currently live in Toronto, and it’s the city I consider home.”

See? Mini biography right there.

I’m what people call a “third-culture kid.” The term is defined as someone who grew up away from his or her parents’ culture for a long period of time. My parents are third-culture kids too, which is pretty common in Hong Kong. There’s a large Indian community there, and many people have citizenship from other countries.

With today’s world being more internationally connected and accessible, third-culture individuals, as they are also called, are becoming more and more common. Even President Barack Obama is a third-culture kid.

According to Paradis & Crago’s 2011 book “Dual Language Development and Disorders: A Handbook on Bilingualism and Second Language Learning,” there are as many bilingual children in the world as there are monolingual children. And third-culture kids (or TCKs as they will henceforth be referred to) often have the advantage of being at least bilingual if not multilingual.

If you’ve heard of third-culture kids, you have Dr. Ruth Hill Useem to thank. She was the leading researcher of the TCK phenomenon. She has a Ph.D in Sociology, Anthropology, Social Psychology and Psychology. Along with her husband, John Useem, and Dr. Ann Baker Cottrell, she conducted research in over 70 countries and wrote articles and books on the subject. Ruth, Ann and John, co-authored a series of five articles on TCKs.

One of these articles is entitled, “ATCKs have problems relating to their own ethnic groups.” (“ATCK” refers to “Adult Third Culture Kids.”) Cottrell and Useem talk about how ATCKs have an international mindset and continue to have it throughout their lives. Most ATCKs say that the skills they learned through being an ATCK were underutilized because of a lack of opportunities to actually use them. They also explain how they need an international touch in their lives and do so by speaking foreign languages, traveling and volunteering abroad, or even welcoming the chance to meet people from other countries.

In addition, ATCKs are characterized as adaptable and people who can relate easily to a huge diversity of people, “regardless of differences such as race, ethnicity, religion or nationality,” according to the article.

ATCKs enjoy solving problems and helping people, mainly through mediation and they don’t identify with members of their ethnic group. This lack of identification can create isolation, especially in recently returned ATCKs, and “for some, this feeling lasts a lifetime.” They see themselves as more global citizens and feel at home in multiple places.

According to the article, women and men have different responses to being ATCKs. The female respondents expressed more difficulty in leaving childhood friends and stress over deciding whether they want to settle down or travel, but they make friends more easily than men and are prone to see different points of view. Men expressed more satisfaction because they were less concerned with making friends than with overall external achievements.

While no one I know was part of this study, I can confirm this as true for the TCK community in Hong Kong. Many of the people I interacted with were TCKs in one way or another, and most of the males I knew enjoyed friendships but preferred the ones they started with rather than making more friends. They enjoyed achievements, like excelling at sports or chess or getting into the best universities.

Whereas my female friends were always distraught at the notion of leaving their best friends to go away to university, but always enjoyed the idea of travel.

My culture views “settling down” as mutually exclusive with global travel unless it has something to do with business and spouses are along for the ride. Most female third-culture kids feel the need to travel as young adults before they get married. I can’t tell you how many times someone has told me:

“Better do all this now, puttu, before you settle down and get married!”

Another of Cottrell and Useem’s articles is “TCKs Experience Prolonged Adolescence.” According to this article, most TCKs find it difficult to decide what they want to do.

The article reads: “Some young adult TCKs strike their close peers, parents and counselors as…not being able to make up their minds about what they want to do with their lives, where they want to live and whether or not they want to ‘settle down, get married and have children.’”

This is what people describe as “delayed adolescence”.

However, most ATCKs are actually people who are interested in learning about themselves.

“Their prolonged/delayed adolescent behavior is usually a marker that adult TCKs are trying to bring order out of the chaotic nature of their lives,” the article continues.

In other words, they are concerned with finding the right path for themselves, which can be difficult with the many different cultures they’ve been exposed to.

However, if they try to conform and find that the expectations of them are unacceptable to them, “they will quietly withdraw rather than make fools of themselves or hurt the feelings of others.”

But there are TCKs who do not do a lot of soul-searching because it is easier to do what is expected of them in their primary culture. Conformity is important so that attention is not drawn to them.

This article also holds true for many of us. Many of the TCKs in my Hong Kong community felt that they were obliged to seek out careers that are lucrative because that is what expected of them. I know many TCKs who dreamt of being writers, artists and dancers and only a few of them ever followed through with it and succeeded. We conform to keep everyone happy. I know I certainly felt like I had to while I was growing up. I’m very glad my parents disabused me of that notion. Conforming is exhausting.

Personally, I am a strange case. My mother tongue is Sindhi, but I barely recognize when it’s being spoken to me because my mother spoke English to me during my formative years in Vancouver. I understand bits and pieces of Hindi and Cantonese, but not enough to speak either fluently. I learned French and Mandarin in school until I was functional in one and passable in the other. Since I stopped utilizing both languages after the age of 15 and 18 respectively, English is really the only language I know.

I’m not totally unique, since I went to a school that had a lot of TCKs, but I feel like I have a unique perspective, because I’m also the child of two TCKs. My father was born in India, lived there until he was 6, then moved to Hong Kong, went to Tennessee for college for six years, moved back to Hong Kong to get married, and then immigrated to Vancouver for five years, after which he moved back to Hong Kong. But while Hong Kong is his home, he misses Canada.

And considering that the only long-standing argument between him and my mother is over the air conditioning, my guess is weather has something to do with it. Like me, he knows what isolation as a TCK feels like.

“When I first came to HK, I did not know the language and it took a while to become a part of the community. When I was in the US, there were occasions when I felt like an outsider,” he said.

He revealed a part of himself I hadn’t known before. He and I were the same age when we came to Hong Kong, so he understood the “new kid at school” phenomenon as well as not being able to relate to his classmates because he was a very recent immigrant. But he certainly made up for that isolation with learning six languages— English, French, Cantonese, Hindi, Sindhi and basic Mandarin. Yes, the first five of those are fluent. If you want to know where I got my love of learning from, it would be from him.

My mother was born and raised in India, moved to Hong Kong after marrying my father, then moved to Vancouver two years after having me, got her citizenship after five years and then moved back to Hong Kong, where she’s lived ever since.

Unlike me, she never felt at home in Vancouver the way she does in Hong Kong. She speaks five languages—English, Hindi, Telegu, Sindhi and some Cantonese. But unlike my father and I, she has never felt like she is without a home. She was able to make a home in India, Vancouver, and Hong Kong, and never once has she felt isolated in the same way my father and I have.

Her reason? “My values are very strong within me,” she said, and knowing my mother as I do, that doesn’t require much explanation.

But I think it’s also because she lived in India until she was 19—she was still a teenager, but she had always expected that she would have to get married and move away around this age. She knew what to expect. My father and I didn’t.

My best friend is also a TCK. She and I have the same Hong Kong history, and both of us are South Asian, but she lives in New York City. And she’s like my mother (not just because both of them go into transports of annoyance when they see my messy room) because she can live anywhere—if she had to move back to Hong Kong, it wouldn’t upset her all that much.

Being a TCK has huge advantages—lots of opportunities to travel around the world, learn about different cultures and meet new people. I know I wouldn’t be the person I am today if I wasn’t a TCK, and I’m grateful for it.

I may not have true national pride for the countries that lay claim to my ethnicity, nationality, and permanent residency status, but it leaves me free to forge my own identity that I am constantly editing and updating.

It keeps me accepting of all religions and nationalities and leaves me free to try and see others’ points of view without judging them. So even with all the uncertainty and isolation while growing up, I’d have to say that being a TCK is definitely worth it in the end.

Raisha Karnani holds an Honours BA in English and Drama from the University of Toronto and has been writing professionally for nine years. Raisha enjoys anything Harry Potter related, munching on Reese’s Peanut Butter Cups and painting her nails.

Raisha Karnani holds an Honours BA in English and Drama from the University of Toronto and has been writing professionally for nine years. Raisha enjoys anything Harry Potter related, munching on Reese’s Peanut Butter Cups and painting her nails.