Summer 2016 officially began on June 21 and ended last week on Sept. 21. To give you an accurate temporal snapshot, however, I, like many others, framed my summer as the beginning of June through the end of August. Fourteen weeks. I spent the first nine of those weeks in agony, studying day and night for the mid-July bar exam. No parties, no meaningful outside contact, and no life outside of my home. But I mustered up one way to enjoy my brief and sporadic moments of downtime: Vintage Bollywood movie breaks.

Once a week, I cuddled with my mom, my dog, or my man, and watched one vintage Bollywood film in hopes of becoming better versed in the classical canon of Hindi cinema. My mom and I went together to a local movie shop and bought a stack of DVDs. I let her pick her favorites. Lord, she nearly picked solely movies with Dharmendra as the lead hero before I stopped her and requested that she diversify her gaze to a broader scope of hunks. In the end, our purchases spanned from 1950-1970s Bollywood, featuring everyone from Vyjayanthimala to Madhubala to Hema Malini; from Dharmendra to Dilip Kumar to Amitabh Bachchan when his head and beard matched in color.

To be honest, I was fully expecting these films to be cheesy romantic sagas with redeeming banger songs. And I was right. But I made a few other observations that struck me in terms of the expressive transformation of Bollywood from then to now in terms of feminist themes and positive Muslim representation.

To begin with the feminist realm of my observations, I was surprised to see such strong and deliberate female roles on camera during a time when I was positive they would be cast as one-dimensional entities of subservience.

Oh, no.

[Vyjayanthimala in Nagin (1954)/Movie Still]

Anarkali told the Mughal Emperor to shove it, as she would rather die than have him dictate her love life in “Mughal-e-Azam” (1960). Mala, an Adivasi tribe leader’s daughter who broke into orgasmic sweats every time she heard her lover from a rival tribe play his flute, went against her own tribal laws (and family loyalties) to pursue her own desires in “Nagin” (1954). Far more fascinating than these on-screen heroines, however, were the colorful lives that all of these actresses led off-camera.

Madhubala was a key breadwinner for her family from the age of nine when she first started acting in films. She landed her first role as a heroine at the age of fourteen in “Neel Kamal” (1947)—a fact that is both impressive and a little disturbing considering she acted opposite twenty-three-year-old Raj Kapoor. Although she only had fifteen box office successes out of her vast portfolio of films, she was, nonetheless, revered as the most iconic actress of her time. She died shortly after her thirty-sixth birthday from a ventricular septal defect, and yet, she was able to leave an everlasting and profound mark on Hindi cinema during her short life.

Vyjayanthimala was the first South Indian actress to gain national popularity, thus forging the way for other South Indian actresses in Bollywood. In addition to her long career as a successful actress and professional dancer, she has also enjoyed a meaningful political career, serving a six-year term on the Indian Parliament and gaining primary membership in the Indian National Congress Party.

Vyjayanthimala resigned from the latter post citing that the party had eventually lost touch with its grassroots thus making it impossible for her to continue to serve while being at peace with her conscience.

Meena Kumari, donned The Tragedy Queen, was a brilliant poet with couplets that are still reverently recited in her honor. More importantly, she led a life of personal resilience as she struggled deeply with depression and alcoholism. She died at the age of thirty-nine from cirrhosis of the liver. The epitaph that she requested be etched on her grave read:

“She ended life with a broken fiddle,

With a broken song,

With a broken heart,

But not a single regret.”

The power that is nestled in their life stories went beyond any expectations I had regarding feminist examples in the early days of an industry that is largely known for belting out films that would make activist and American feminist Betty Friedan sob. Fourteen weeks of pleasantly surprising exhibitions of twentieth-century womanhood.

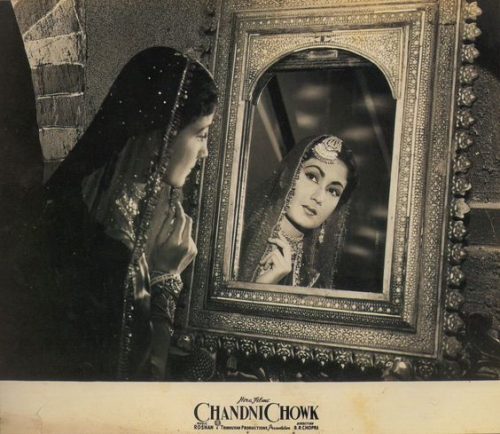

[Meena Kumari in Chandni Chowk (1954)/Pinterest]

On the same wavelength of surprising observations, the depiction of Muslims in pre-1970s Bollywood films proved a far cry from current demonization of Muslims in Hindi cinema as betel leaf chewing villains with violent agendas. For the last two decades, the industry has been dominated by men adoringly known as the “King Khans.” Yet these Khans are consistently cast as Rajs, Devs, and Prems. When Muslim characters are actually written into films, they, especially men, are often used as props for representing moral darkness.

- They are the kohl-smeared dons plotting evil from the insides of masjids, while the pure heroes perform aarti (“Agneepath” 2012).

- They are presented as normal, everyday characters (finally!), only to eventually reveal themselves as murderous, undercover terrorists—a representation that sneakily justifies prevailing villainous conceptions of Muslim men and contributes to their social alienation (“Kurbaan” 2009).

- They always live amidst a turbulent backdrop of violence, suffering, or suspicion, and rarely as leading normal and dignified lives (“Roja” 1992, “Mission Kashmir” 2000, “Fiza” 2000, “Dhoka” 2007, “New York” 2009, the list goes on and on).

[The bad guys. Agneepath (2012)/GIPHY]

[The good guys. Agneepath (2012)/GIPHY]

Bollywood’s villainous Muslims have led many South Asian Muslims to reject the industry entirely, opting for other cinematic avenues of cultural consumption. While I have not yet explored those alternatives , as a Muslim woman I am all too familiar with the discomfort that stems from Bollywood’s use of Muslims as props for immorality and/or as the non-plot-furthering family next door for the sake of feigning inclusion. Prior to 1970, however, Bollywood sang a very different tune when their films focused on Muslim characters.

The dignified portrayal of Muslim characters in early Bollywood films was a proverbial hug that I did not know I needed. It wasn’t just the overdone Mughal emperors and their glamorous courtesans. I stared, glassy-eyed, as I watched “Najma” (1943), “Chandni Chowk” (1954), and “Bahu Begum” (1967), gawking at the humanization of the business-savvy nawabs and singing begums that are so tragically lacking in today’s films. There were no terror plots, but there were Qawwali battles; there were no militants, but there were naïve princes and overconfident poets. To see your spiritual community positively represented in an industry that has devotedly alienated it during your lifetime is both a form of healing and a form of pain. Fourteen weeks of rediscovering what real and positive representation looks like, because it has become such a foreign concept to Muslims throughout the world today.

[Photo Credit/GIPHY]

These representations were also an appreciated reminder of the beauty that is the South Asian brand of Islam—a tradition imbibed with music, dance and poetry, but now tragically falls prey to the tyrannical criticisms of Saudi clerics who deem all things that fall out of the scope of Arab custom as sinful innovation. This has led to more South Asian Muslims swapping their salwar suits for abayyas, and their musical traditions for more rigid interpretations of proper social engagement, all for the sake of conforming to what they have been implored to believe is the proper practice of Islam. I spent fourteen weeks reuniting with the beautiful intersection of Islam and South Asia.

Fourteen weeks of ravenously drinking the ambrosia of my womanhood and Islam. Fourteen weeks of renewed hope for an industry in which I had nearly lost all hope. If they were once this bearable, they can surely do it again! From dancing heroines challenging the social structures of their conservative villages, to Muslim poets reciting couplets in courtyards dripping in roses, these fourteen weeks of vintage cinema reconnected me with a history I could barely recollect, but deserved to know.

While I wait for the industry to transform positively once again, perhaps I’ll finally spend the next fourteen weeks exploring alternative industries for cinematic consumption (i.e.: Lollywood (Lahori) and Dhallywood (Bangladesh)) as so many other South Asian and South Asian Diaspora folks have done, as it really is saying a lot if the 1950s look like a better place than where we are now. My fourteen weeks of perusing the archives of Bollywood cinema have reaffirmed that as cultural consumers, we deserve so much more than what we receive today.

Elizabeth Jaikaran is a freelance writer based in New York. She graduated from The City College of New York with her B.A. in 2012, and from New York University School of Law in 2016. She is interested in theories of gender politics and enjoys exploring the intersection of international law and social consciousness. When she’s not writing, she enjoys celebrating all of life’s small joys with her friends and binge watching juicy serial dramas with her husband. Her first book, “Trauma” will be published by Shanti Arts in 2017.

Elizabeth Jaikaran is a freelance writer based in New York. She graduated from The City College of New York with her B.A. in 2012, and from New York University School of Law in 2016. She is interested in theories of gender politics and enjoys exploring the intersection of international law and social consciousness. When she’s not writing, she enjoys celebrating all of life’s small joys with her friends and binge watching juicy serial dramas with her husband. Her first book, “Trauma” will be published by Shanti Arts in 2017.