Originally published on Maryam Jameela’s blog.

With the 6th printing under its belt, the new incarnation of “Ms Marvel,” Kamala Khan is clearly a giant hit. Its phenomenal reception has resulted in numerous articles praising its diversity and likeability.

Noah Berlatsky of The Atlantic writes:

“Changing shape doesn’t mean that Kamala erases her ethnicity, nor, in the way of Superman, that she is forever split between nebbish and overman. Rather, in “Ms Marvel,” shape-changing seems to suggest that flexibility is a strength. Kamala is a superhero because she’s both American and Muslim at once. Her power is to be many things, and to change without losing herself.”

This is the crux of why “Ms Marvel” works so well; she has intersections up the wazoo (a Pakistani-American daughter of immigrants, Muslim and female) but the character and plot developments are masterfully balanced between embracing her difference without erasing it or tokenizing it.

As a Pakistani-English daughter of Muslim immigrants, there are a few things about “Ms Marvel” that make her the greatest thing that has ever happened to me. There are quite a few great articles about why “Ms Marvel” is the bomb so I don’t feel like I need to do much in the way of talking about how great “Ms Marvel” is, but I’m going to give a shot at explaining why Kamala is so important.

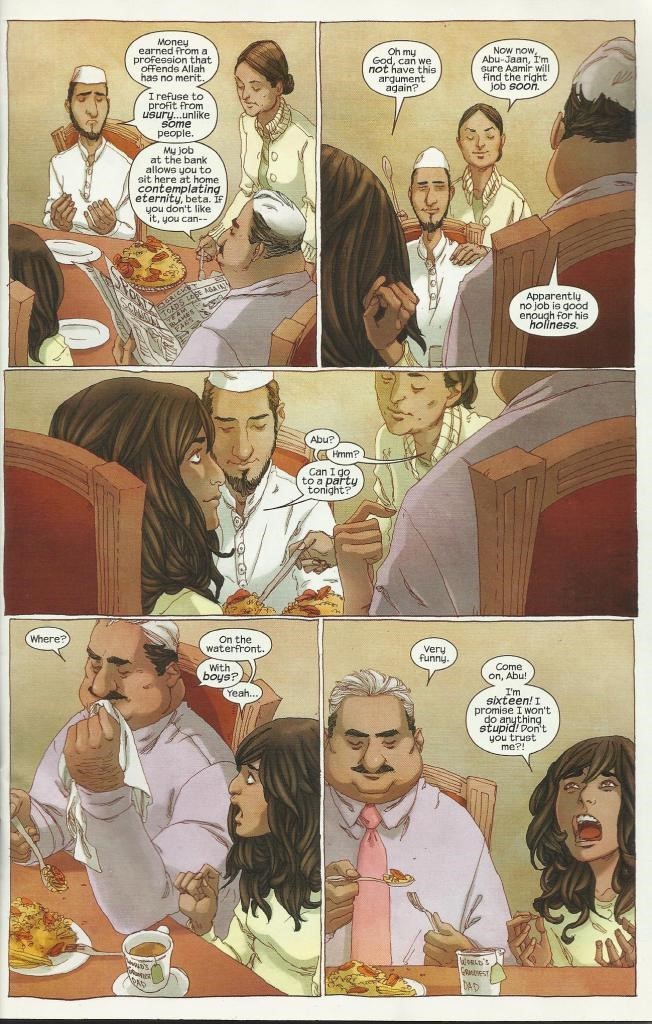

The dinner table scene—Kamala has already been shown at home and with her friends. There’s no quicker way to humanize characters than to show their relationships at home and with friends. It automatically positions the reader on ‘her’ side and thus normalizes everything about the panels: their clothes, their food, their house, THEM.

“Ms Marvel” #1

Marvel has had Muslim characters before, but to have a Pakistani-Muslim-American girl is goddamn revolutionary. Kamala sitting at her desk and questioning why she has to be different is central to her character development. I’m not used to seeing Pakistani-or, let’s face it, just brown characters. ‘Pakistani’ is not a cultural capital in the ascendancy, with most characters being terrorists, rapists, raped, or fundamentalists. The women are usually plot devices, if there at all, but here is a comic book from the foremost comics publisher with a brown girl as the hero. A brown girl that gets to struggle with normal teenager stuff (read: white teenager stuff) and her superpower is built on wanting to change how you look.

The final page of #1 with Kamala as white, blonde and tall didn’t have me worried the first time I read it. There were a few Tumblr posts about possible whitewashing or just complete confusion at the time of publication. But, I get it. I just get it. The plot of the first issue especially is one that I feel I have literally been waiting all my life to see (I have a tendency towards hyperbole, but, disclaimer: I mean it. In this post, I mean it all). Wanting to be white is written into your existence if you aren’t white and I still can’t quite believe that G. Willow Wilson went there.

Not including this comic series, exactly four media products have made me cry in the last few years (“Toy Story 3,” NBC’s “Hannibal” [out of disgust still counts], “Lucy” by Jamaica Kincaid and “The Dew Breakers” by Edwidge Danticat). So I’m not a frequent crier, but add “Ms Marvel” to the mix and I’m bawling anytime I go near it.

It’s a shock to see yourself represented, it’s a shock to see a character having a carbon copy of a conversation you’re continuously having with people and it’s certainly a shock to see yourself represented in a resoundingly positive manner.

![[Source: Marvel.com]](https://browngirlmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/Ms-Marvel-2-327x500.jpg)

“Ms Marvel” #2

“It’s almost like a reflex. Like a fake smile. Like I have to be someone else. Someone cool. But instead I feel small.”

![[Source: Marvel.com]](https://browngirlmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/Ms-Marvel-3-671x1024.jpg)

“Ms Marvel” #3

![[Marvel.com]](https://browngirlmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/Ms-Marvel-4-1024x622.jpg)

Kamala sitting in a high school changing room panicking about being able to control her own body is a puberty narrative for brown girls. Saz from “Some Girls” has her awakening sexuality as a prominent arc in season two of the show and seeing the classic puberty-superhero analogy with Kamala, as well as the don’t-be-like-your-mum (even literally) fears manifest are classic. I’m convinced that the song “Mere Khawabon Mein Jo Aaye” from “Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge” is another classic brown-girl-puberty-narrative.

“Ms Marvel” #4

Kamala uses a burkini as the basis of her costume. I have no point about the synthesis of Islam and immigrant life to make here, that shit is just straight up hilarious.

“Ms Marvel” #5

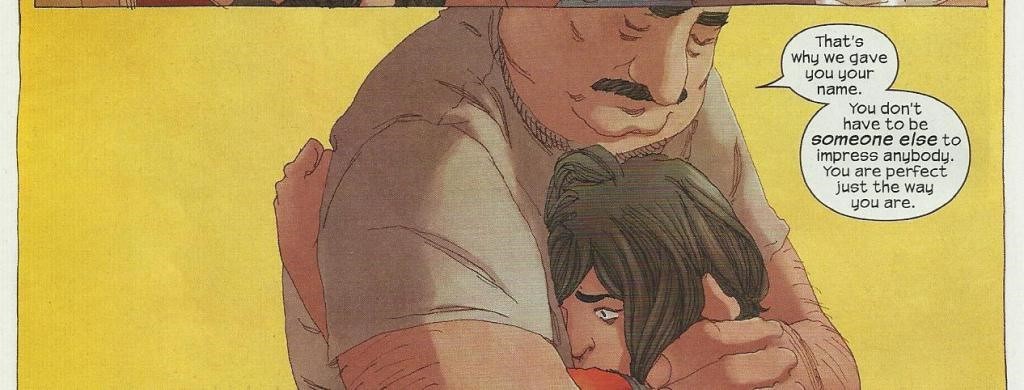

Something as simple as Kamala wanting her mum brings her mother into focus. She remains a side-character for our hero to bring to her life; this is an infinite improvement on the peripheral Muslim mother who either frets in worry for her sons or enables their terrorism. Kamala’s mother seems, until now, to be concerned and annoyed with her daughter – as any mother would be if their kid started sneaking out, wearing a burkini and emptying the fridge. Having Kamala frequently state what both her parents taught her fleshes them out as humans. That seems to be a pretty standard writing 101 comment but, once again, context is key. Kamala’s parents aren’t demonized for their restrictions on their daughter; the fact that they are able to have the odd scene here and there in which they communicate with her and focus on building her character is not only excellent parenting, but excellent parenting from Muslim-Pakistani immigrants. How many times have you seen that happen before in any vehicle of the mass media?

![[Marvel.com]](https://browngirlmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/Ms-Marvel-5.jpg)

If you are Muslim, and an immigrant, or a second-generation immigrant, or brown, or a woman, or anything else that isn’t typically considered normative – it needs to be communicated in some way to you that you are valid and that you are seen. That is exactly why representation matters, so you can become visible.

I would have given anything for 10-year-old me to be able to read this comic and see myself staring back at me. Or, at least, 23-year-old me can see that and 23-year-old me is able to appreciate it. Kamala’s very superpower is a manifestation of racial issues, religious issues and, amongst other things, issues that come with being an immigrant. She gets to change herself into anybody or anything she wants to be and what she chooses to do is suit up and save people because ‘good is not a thing you are, it’s a thing you do.’ I mean, can I get a woop woop?

“Ms Marvel” #6

Kamala is told by her father to visit Sheikh Abdullah for a ‘talk’ and she assumes that the Sheikh will lecture her about boys and advise her to stop lying to her parents. Instead, he says:

If you insist on pursuing this thing you will not tell me about, do it with the qualities befitting an upright young woman. Courage, strength, honesty, compassion and self-respect.

To depict a high-ranking figure sitting in the mosque with a young woman and telling her to trust in her own qualities is yet another representation that trusts in the individuality of the role. The Sheikh is not a central figure, but his influence is kind-hearted and well-meaning without patronizing Kamala or questioning her choices. Just as the Sheikh preaches caution without restricting Kamala, Kamala herself can think his lectures boring and also take his advice as a respected member of their community. These are not quirks or contradictions, but nuances. Such nuance indicates the depiction of people and that is something that is noticeably missing when it comes to representing Muslim, brown and/or immigrant people.

Other people who belong to any or all of those categories have been talking for a while now, but “Ms Marvel’s” very existence is changing the landscape of how Muslim people are represented and how we are seen. Kamala Khan is the vehicle for mass appreciation of the classic superhero trope – the humanity in the superhero is the compelling part.

Maryam Jameela lives in Lancashire, England. She graduated with a B.A. in English literature and an M.A. in gender studies. She is passionate about writing all things desi and will begin her Ph.D research into desi film and literature at the University of Sheffield, U.K. in the fall. You can read more things that she has written here.

Maryam Jameela lives in Lancashire, England. She graduated with a B.A. in English literature and an M.A. in gender studies. She is passionate about writing all things desi and will begin her Ph.D research into desi film and literature at the University of Sheffield, U.K. in the fall. You can read more things that she has written here.