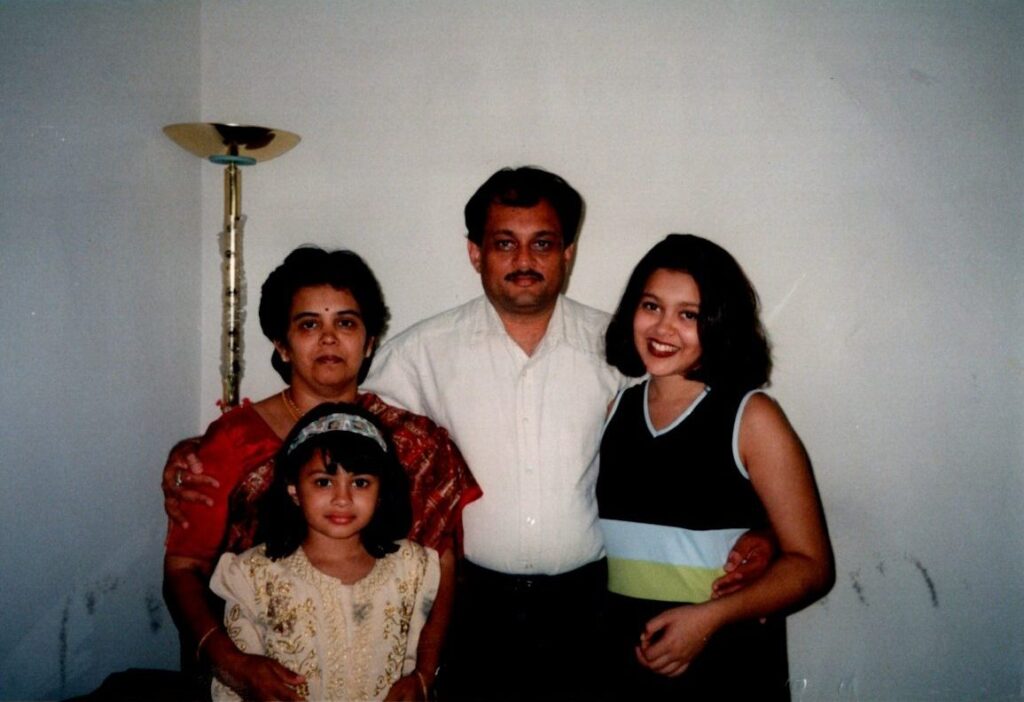

Photo Caption: Author and her family on author’s sixteenth birthday. Photo Source: Manoshi Vin

As a teen, I remember reading a story in “Chicken Soup for the Teenage Soul” titled “Where Do the Mermaids Stand?” The story was simple: The narrator is playing a game of Giants, Wizards and Dwarfs in which children were required to pick a team. A little girl approaches the narrator and states that she is a mermaid without a doubt; and needs to know where she should go. What amazes the narrator is the conviction to which this little child knows who she is and where she belongs. As a 14-year-old immigrant living in Georgia, this stuck with me. I was not a mermaid—not yet.

I moved to the United States when I was 12 and as a teen, as most teens do, assimilated into my mostly white world much quicker than my parents. In hindsight, my racial passing for a Caucasian person protected me from the overt discrimination that some of my family and friends endured. I was too young to understand how microaggression and institutional racism impacted my identity. I did not understand the privilege that my skin provided me.

Many years later, I was a work-study student for a professor at Boston University School of Social Work. The professor, himself a person of color, was researching how a mostly white student body responded to an educator who was not. Deep into research one day, he posed a simple question in front me—how did my white counterparts see me, a woman of color? I still remember the silence in the room when I looked around for the woman of color—I clearly was not it. I reassured him that he was mistaken, I was Indian, not a woman of color. I had a strong cultural identity but my color, well, it had never presented itself. There was now silence on his end.

[Read Related: Understanding my Privilege by Learning South-Asian American History]

I remember staying up that night, coming to terms with the title Woman of Color. It felt negative, discriminatory and raw. I felt a bubble of confusion followed by anger. I remember staring hard into a mirror trying to see what he saw and that is when I saw it. My privilege, which I had mistaken for my right, was staring me right in my face. My transformation had begun.

In the decade after this night, I became a therapist, a wife and a mom. The mermaid in me took backstage to the other hats I was wearing. Then one day in late 2019, the issue of color returned for me. My three-year-old daughter had returned home from preschool with a dilemma. During recess that day she explained, she wanted to play Elsa turned Captain Marvel but her friends told her she could not. Their and her reasoning was simple, Elsa and Captain Marvel were white with blonde hair, she was dark-skinned with black hair. As I watched her struggle, I was startled by the fact that at three, she had already received the message that her skin made her different than her cherished heroes. At three, the color of her skin was apparent to her and was already becoming a barrier to what she wanted. The protection and privilege that my skin had provided me were not extended to her. A familiar feeling of anger began to rise.

[Read Related: Connecting With the Past and Reclaiming my Identity Using Poetry]

As a therapist and a mom, I often engage in conversations about race and identity and I think back to the story of the mermaid. While I admire the mermaid for knowing exactly where she belongs, I also have come to realize that this story is misleading. It assumes that all players in the game are equal and while the mermaid may be different, she still possesses the privilege to pick where she belongs. We know this not to be true. We know that some are be awarded the luxury of mobility and others are limited by their color, race, language, gender, sexual orientation and socioeconomic status. And while they may know exactly where they belong, they are not able to get there.

As for my daughter, she woke up the next day with a solution to her dilemma. Overnight, she had concluded she no longer wanted to be Elsa turned Captain Marvel, but she was going to be her own version of a crime-fighting princess who had dark skin and black hair.

Manoshi Vin is a board-certified psychotherapist specializing in pediatric, adolescent and adult mental health based in Seattle, WA. In addition, she is a wife and mom of two brown girls.

The opinions expressed by the writer of this piece, and those providing comments thereon (collectively, the “Writers”), are theirs alone and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of Brown Girl Magazine, Inc., or any of its employees, directors, officers, affiliates, or assigns (collectively, “BGM”). BGM is not responsible for the accuracy of any of the information supplied by the Writers. It is not the intention of Brown Girl Magazine to malign any religion, ethnic group, club, organization, company, or individual. If you have a complaint about this content, please email us at Staff@browngirlmagazine.com. This post is subject to our Terms of Use and Privacy Policy. If you’d like to submit a guest post, please follow the guidelines we’ve set forth here.