Just in time for Valentines Day, Tanzila “Taz” Ahmed, shares the inspiration behind her 18-card collection of novel, creative and funny #MuslimVDay cards. Taz is an artist, writer, political activist and creator of Mishthi Music, a blog that highlights music of the South Asian American diaspora. Read on to discover how Taz took action in the aftermath of the Bangladeshi garment factory collapse, and how she began a national organization at the age of 25 .

Tell us about your upbringing in a Bangladeshi family while living in California.

I was the kid who wasn’t allowed to go outside after the streetlights went on, but it didn’t really matter because I had my nose buried in books for most of my youth. My dad migrated to California in 1969 on the dawn of the creation of Bangladesh – he was a Bangladeshi who never technically lived in Bangladesh – so I’ve spent most of my life living on the legacy of flux. I spent my career as a political activist, writer, and artist exploring the space of this hyphenation of identity politics, constructing, dismantling, de-colonizing, narrating, empowering. And because I’m a Southern California girl, I did it usually while riding a longboard skateboard, having colored hair, or being in punk pits.

You started South Asian Action Voting Youth at the age of 25 (wow!). Tell us how you became involved in community activism and how you started your own national organization.

It’s the typical 9/11 story – though at the time, it didn’t feel so typical. I was living in Washington DC in 2001, first job out of college. I would help youth create electoral campaigns to save the environment. And then 9/11 happened, and for the first time ever, I really had to confront what it meant to be a brown American in hateful backlash fueled environment. A friend took off her hijab, I couldn’t fly anymore without a special call being made, my folks stopped going to the mosque, flag stickers everywhere. The worst though was when FBI came knocking on my parents house – and my Mom said, ‘It doesn’t matter that I’m an American citizen or how long I’ve lived here, I’ll always be a second class citizen.’

When I was ready to move on, someone asked me what my dream job would be. And for me, it was to do the same thing I was doing – creating a political voice for a people. At the time, there was nothing like that. No one was interested in giving South Asians or Muslims a political voice. It’s a lot different now.

Within months it snowballed out of control and we called the project South Asian American Voting Youth (SAAVY). We found a fiscal sponsor, a large board of South Asian leaders and we were able to establish South Asian youth fellows and campaigns in Michigan, New York, Georgia, Florida and California. It all moved really fast, and it was a crash course in founding a non-profit. The thing is – when you start a project in your mid-twenties, you have tons of energy, hope inspiration and optimism. Everyone needs to have one project in their life that defines them like that. I look back at that time in my life in total awe.

What is the inspiration behind the “Muslim VDay” cards?

It was right before the book ‘Love, Inshallah’ came out around Valentine’s Day – my story ‘Punk Drunk Love‘ was published in the anthology – and I was thinking a lot about what it meant to be a Muslim woman who was trying to be in love. I was struck particularly by how the climate of hate and fear of Muslims meant that the ‘outside’ world had a particular narrative of what it meant to be a Muslim woman.

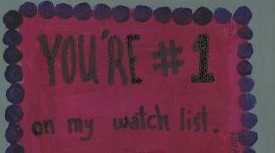

Burka-ed, arranged marriages, not in love, exotified, what not. I was also silo-ed for being a single Muslim woman. Inside the community, I wasn’t good enough – I didn’t wear hijab, was too old to be marriageable, too independent to be lusted. So I wanted to break both perceptions, and destruct the narratives and perceptions that people placed on me. So I tweeted the kind of Valentine [card] that I would have loved to receive – something funny, cheeky and made you think – “You’re the bomb #MuslimVDay” – and then I kept tweeting. I’m an artist too – so I painted six of the hashtags as actual cards and photocopied them for friends. They loved them.

The cards aren’t for everyone. But I see them as a form of radical art that challenges people to think about their ideas and perceptions. And they’re cute and funny. And who can’t get behind cute and funny?

To purchase a set of the Muslim Vday cards, visit Love Inshallah orEtsy.com.

What is the concept behind the blog Mishthi Music? And how was it like to work with Brooklyn Shanti and create Beats for Bangladesh?

So Brooklyn Shanti and I met sometime in the spring of last year when he came out to LA to do a show. He’s one of our favorite artists at Mishthi Music and I was super excited to meet him.

When the garment factory collapsed, I reached out to him to see if he wanted to do something about it. Since I have family in Bangladesh who works in the garment industry, we were organizing vigils here in LA, and I just felt like we could do more. Shanti was doing stuff in NY too.

We then decided to put out Beats for Bangladesh. Brooklyn Shanti did all the musical executive producing and I did all the community organizing. I particularly wanted to reach beyond just Bangladeshi Americans. So often in the U.S., Bangladeshi issues are marginalized by the Indian-American narrative. By making this a pan-South Asian American music project, we wanted to make a political stand on how this was a South Asian solidarity issue.

Since you have a lot of artistic endeavors, tell us about your poetry and where you get your inspiration from.

I’ve always written – but I think I didn’t recognize poetry as a contemporary art form until I started going to spoken word spaces in the mid-2000s. It was eye-opening to see people vulnerably share their poetry on the mic. So I started writing poetry more, eventually jumping on the mic. Luckily Los Angeles has a lot of safe spaces for people-of-color poetry, which really helped me to write and share.

I think for me writing in general has to come from a place of inspiration. I admire people who can write for a living, but I realize that it’s simply not something I’m able to do. Though I write prose and poetry – I moved away from writing after my mother died two years ago. To sit in that space was really too frightening – so I shifted to painting, which I found more meditative. I’ve only recently tried to move back to writing and I’m consciously trying to cultivate spaces of inspiration, warmth and love to get me to write again.

You seem to have followed a “non-traditional” career path that many traditional-minded parents would frown upon. What advice can you give to our young readers about choosing a non-traditional career path?

I think non-traditional paths are frowned upon only if parents see you are not being serious. At the end of the day, your folks just want you to be successful. It’s about finding that compromise. My advice to youth is that your parents will get over it, just give them time. Don’t mooch off them and give them a reason to be proud. And parents are oddly proud in weird ways – such as getting featured in India Abroad and suddenly your parents see you are legitimized. And if you are going to go the non-traditional route, be really successful at it.

What advice can you give to girls who want to start a career in public policy, community organizing/activist or poetry?

When I was a teenager, I never would have imagined the trajectory my life would have taken. The consistent themes in my life have been a) creating a political voice for marginalized Asian/South Asian communities through the electoral process and b) collecting and telling narratives of the South Asian American community through words, arts and poetry. So my advice is a) make art always – write, poetry, painting, whatever b) build on personal legacy and listen to stories, c) live your life justly and righteously – social justice “work” isn’t something you do on the side but something we must incorporate as a value into every aspect of our lives, d) pick the path that leads to the better story and e) if you live a life like this – you will upset people, fight, burn bridges, have trolls, stalkers, etc. You just need to be okay with not making everyone happy and that comes with the territory. And similarly, you need to learn to love, forgive and let go.

Tell us how youth can take part in the four-day summer camp, Bay Area Solidarity Summer?

For the past few years I’ve been involved with Bay Area Solidarity Summer (BASS) – it’s a four-day camp we created for young South Asian American activists to learn about issues going on in the community and to meet other like minded people and basically. It’s the camp I wish I had when I was teen. I think for anyone younger that wants to get involved, this is a great starting point. I am totally envious of the youth today and wish I had access to something like these camps when I was a kid.

All photos are provided by Tanzila “Taz” Ahmed.