Jhumpa Lahiri’s “The Namesake” was the first book I read that had a family of South Asians as the main characters. I saw glimpses of my Punjabi family in the conversations and interactions of an immigrant Bengali family living in New York. I saw two generations of the same family clashing and diverging, and then coming together as the family faced questions of loss, identity and understanding of their heritage. For my young mind, it was such a revelation to see an imperfect yet deeply caring South Asian family that reminded me of my own.

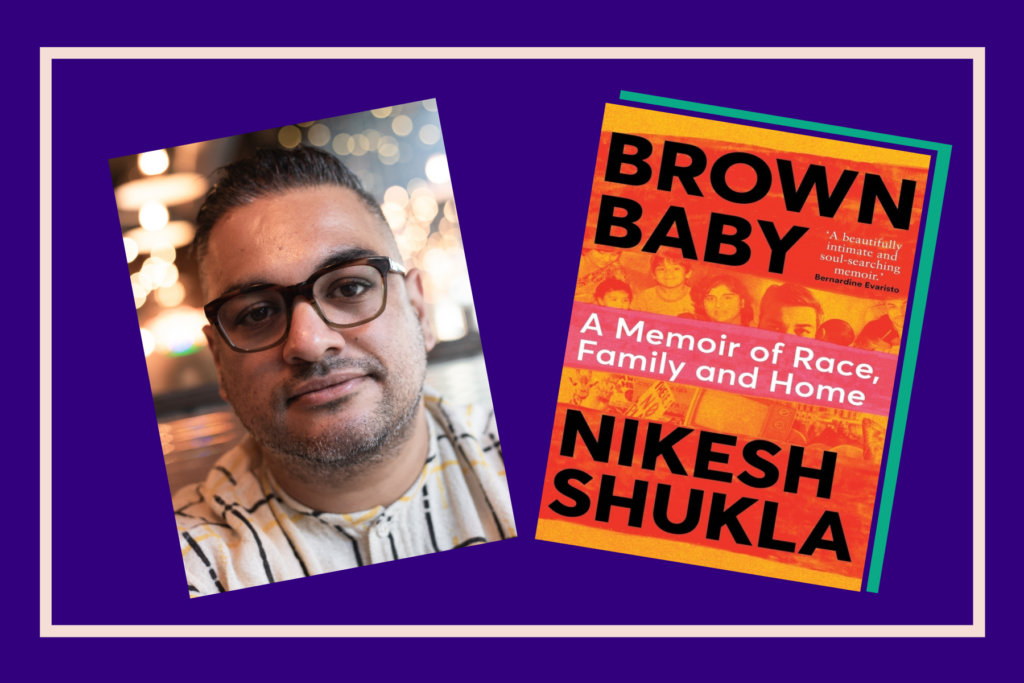

Nikesh Shukla’s “Brown Baby: A Memoir of Race, Family and Home” is the first book I have read where a South Asian father, to two young daughters, openly and vulnerably states that he isn’t perfect. And turns to food as an emotional crutch. And, most of all, is terrified about the state of the world and is the first to admit that he doesn’t have all the answers. For my adult mind, it is such a revelation to see a Brown man take up space and say that he makes mistakes. And that it is okay to make mistakes.

Mind you, I was a tad skeptical when I picked up the book. As a woman who grew up in a South Asian community, I have seen my fair share of uncles who seem to have rigid notions of masculinity and prescribed beliefs about the role of women. Do we need a memoir of a Desi man telling us how hard it is to raise women in a very patriarchal society? This initial reaction was a thought that I even shared with Nikesh during our Zoom, a thought that he accepted graciously. And only after reading the memoir did I realize that we are in dire need of Nikesh’s words – his humorous, sometimes searing, and insightful words. I learned that it isn’t just a memoir about raising children. It is also about how to raise ourselves when we lose a loved one. How we pick up ourselves and charge on when everything around us seems to be crashing down. Most of all, how we survive, grieve, thrive and live as Brown people in this world.

[Read Related: Book Review: ‘Unfair’ by Rasil Kaur Ahuja Explains Colorism to Children Through Storytelling]

“Brown Baby: A Memoir of Race, Family and Home” is an epistolary-style memoir of Nikesh bestowing his thoughts, wisdom and confusion about the world in letter form to his mixed-race daughter, whom he calls Ganga. Nikesh describes his memoir as “a book about how we raise our kids to be joyful in dark times when we are so sad and angry.” Each chapter is written almost like an instruction manual – from topics ranging from ‘How to talk to you about the end of the world’ to ‘How to talk to you about your heritage’ that are anchored with anecdotes of love, joy and pain. But as Nikesh shares with us, the reader, his journey of learning how to be a father to his mixed-race daughters, he also allows us to sit beside him as he processes his grief over his mother’s death that occurred over ten years ago. If he was writing a book as a parent that was about finding hope in dark times, he had to dig deeper and process a dark time of his own.

“I had to experience her dying again through writing her into existence and writing her out of existence. It was the most painful thing I’ve ever done.”

Nikesh’s mother passed away in October 2010. A week later, his first novel was released. For Nikesh, he thought the best thing would be to distract himself with the literature events and parties, rubbing elbows with famous authors, and basking in his big moment.

“I was feeling loved in a fleeting way [that happens] when you’re doing these things when you’re going through the treadmill of these events.”

He didn’t realize that at the time, he was pushing down and delaying the processing of his mother’s death. It was when he had his first child that Nikesh felt his mother’s absence:

“I hadn’t prepared myself to be a father without my mum.”

It is with this same level of honesty and rawness that Nikesh writes. He writes openly about how he turns to food as a way to find comfort; About the various snacks he pockets and eats when running errands; About feeling guilty and conflicted about his friends and relatives holding his baby; About being the ROI kid who was the only one sent to private school amongst his siblings and cousins. The final product of the book, as he tells me, is very close to the first draft. In an attempt for readers to feel the precariousness of grief, Nikesh wanted to play with time on a craft level, creating a “memoir in flux with linear-like themes that act like fragments of time.” For example, he writes in his book about the truth of grief:

“It is never linear and it is never proportionate or understandable. Especially to other people. It never happens when it should. It doesn’t seem to make sense to anyone else.”

Now over a year into the pandemic, the concept of time is constantly evolving. We’re deep into our own versions of daily routines while also hearing constant chatter of upsetting news. There is also so much to collectively grieve over. The loss of loved ones. The loss of a year’s worth of living a ‘normal life.’ The loss of physical time spent with other humans. I myself have lost my aunt and godmother while being so far away from home, and there are days I’ll feel the pang of her absence when I come across pictures or things that remind me of her. Hearing heartbreak in Nikesh’s words reminds me that a man as accomplished and as well-spoken as Nikesh is just human as well.

“I’m trying to take it easy dealing with this now and not back then. I’m still trying to forgive myself.”

I asked Nikesh if he had any fear of being so honest and open on paper. He, a prolific fiction writer, dove right into non-fiction writing in a subject matter that was so personal.

“Of course there was fear. When you write fiction, no matter how close you are to fiction — and I always am close to fiction because it comes from a very emotionally truthful place — I could always hide behind the fiction when I’m talking about it in the abstract to people. With non-fiction, I can’t do that. When I put it on the page it’s fair game for people to ask about it.”

And here I was talking to Nikesh about it all over a Zoom call. This was the first time he and I had ever met, and I was asking him about anything and everything. Only during a pandemic could I connect with him while he is so far away with his family in Bristol while I am seated in my apartment in Los Angeles. And only with the release of his memoir could we have such an open discussion about brown masculinity.

“I really want the memoir to constitute what it is like for a brown man to bleed on a page because there isn’t a cannon out there for honesty and vulnerability for brown men.”

He talks about his issues with brown masculinity, Gujrati masculinity, brahmin masculinity, but his hope by being so real is to present a version of himself that isn’t perfect.

“I’m not doing this to represent ‘the sad bois.’”

He tells me and I steal a quick laugh at the peak dad joke. I see moments like this often in his writing, which he himself admits to: reaching for the joke in moments of high emotion. It’s something I see my father doing every time we have a conversation that is heavier than usual.

[Read Related: Book Review: ‘Tears in the Flag’ by Siddharth Bindra]

Naturally, I ask Nikesh about his father. He pauses for a second and asks to skip the question but a second later answers it anyway. I can’t help but smile; Unfolding right in front of me on my laptop screen, I see an example of a Brown man fighting the instinct to remain guarded. And he does so successfully.

“I grew up with the generation of the infallible dad and infallible parent. I wish they had space to be fallible and maybe we would have had a richer time growing up rather than me [still] trying to understand who they are as an adult.”

This is an experience that I myself am going through as an adult who is firmly planted in her 20s. Like Nikesh, I saw my father feel as though he had no space to make mistakes and to be wrong. As the breadwinner of the family, there was a lot on his shoulders to support so many. Only after I left home to live outside of my home country did I connect with my father again.

“I hope to give other brown guys space to be vulnerable and space to sit in their discomfort.”

In fact, the lockdown has allowed Nikesh to find the space to connect more deeply with his male friends who are mostly artists and creatives. The lockdown removed the possibility of “transient pub conversations” as Nikesh calls it for his group of pals to meet for drinks once in a while and “chat shit.” Sometime into lockdown after not hearing from male friends, the group decided to watch a film together over zoom. After a couple of times, they started hanging around after the zoom to have a real heart to heart about mental health and life. They share relationship and career advice and grieve over the loss of loved ones.

“My closest male friends and I have never had that kind of intimacy – lockdown has facilitated that for us. These are men of color as well. I know we have the capacity to be utterly foul but having spaces like these will help us work out how to be better men.”

After reading his memoir and speaking with Nikesh, I am now seeing the new generation of brown men who are taking the space to be vulnerable. For every obstinate desi man, I know someone like my brother who is sensitive and caring. For every troll sending me an inappropriate DM, I have male friends who openly talk about their feelings and tell me if something I have said or done is hurtful. I see men around me who are trying and bettering themselves. And Nikesh is a prime example of a role model we wish we had grown up with.

And I thus annoy him with one question women get asked all the fucking time: has having kids changed your work? The answer: It absolutely has.

“So much of your intentions when you sit down to write like who am I writing this for and why am I writing this now changes. It really focused the audience for the book. It also made me think that if I stretch the possibilities of what Brown people can write, then more Brown people can feel they can write what they want.”

Just like how “The Namesake” made young me realize that imperfect South Asian families could exist on paper and in stories, Nikesh’s book creates more possibilities for the imperfect Brown man.

“I’m willing to be uncomfortable and admit that I’ve messed up. I’m trying to be a better person. That’s all that I can do.”