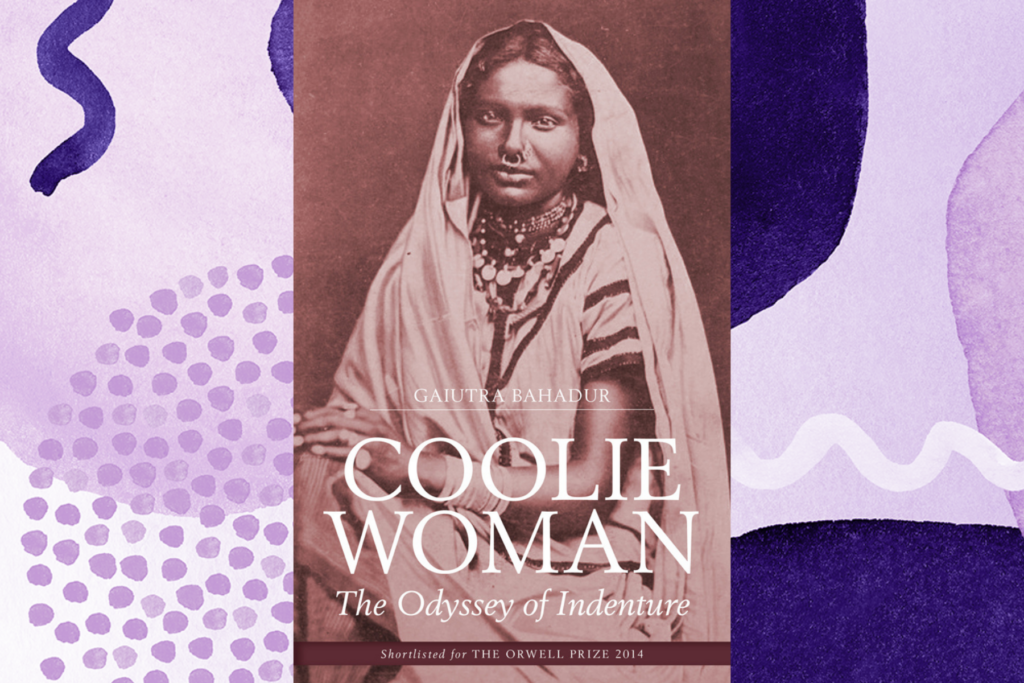

Photo Courtesy of The Caribbean Collective Magazine

“Immigrant number 96153. That’s how my great-grandmother was cataloged, that was the number on her immigration pass,” American journalist Gaiutra Bahadur says in her book “Coolie Woman: The Odyssey of Indenture.”

In this book, she traces the steps of her great-grandmother, Sujaria, who traveled from India to the colonial outpost of British Guiana in 1903. This particular sentence resonates with me because it showcases the elimination of identity. Erasure is an issue that is faced even in today’s society.

View this post on Instagram

Parul Sehgal, the author of “Fighting Erasure, U,” says, “We’re a part of ever-shifting power relationships. Our identities and our privileges are not static, but deeply contextual.” Even after my second time reading the book, I am fascinated by the intricacies of the memoir and how the stories of many indentured women can help continuously pave the way for tackling gender inequalities that are still prevalent in Indo Caribbean culture.

[Read Related: Why I Will Never Celebrate Indian Arrival Day]

Bahadur states that historical ramifications left Sujaria and other similar women voiceless.

“There is a quality of raw abandon in the voices of the women. They spoke in a dialect so private, so intimate to my ears, that every time they opened their mouths, there was a tingling fusion of inside and out, an electric union of outside and in, a sparks-flying soldering together of their soul,” Bahadur says.

The slew of bias and torment truly shines a light on the complexity of their lives. These women dealt with sexual abuse, brutality, mutilation and even murder. After a while, these were common occurrences. The existing archives showcase documents detailing indentured women from the perspective of various men who held power. There is not one narrative or first-person account from a woman or girl. Men in power stole the voices of these women and completely dismantled their lives.

However, I would like to believe that Sujaria and the other women who are tormented and confronted with violence are true heroines. Indo-Caribbean women have come a long way since the era of indentureship, but there are still millions of women who are subjected to violence in their lifetime. According to the World Health Organization, 1 in 3 women experience violence globally. According to the study, the violence may start as early as 15 years of age.

We should learn from our history and use it as a stepping stone for promoting awareness.

While power structures have changed, and more women have a voice. Gender-based violence is a recurring issue and the fight for equality continues.

Unfortunately, for many Indo-Caribbean women, colonialism seeps in our roots, born from a violent past. Violence has emerged in many forms, whether seen in relationships among intimate partners or relationships between parents and children.

View this post on Instagram

In Indo-Caribbean culture, for instance, the act of “giving licks” (beatings) is a form of discipline that is normalized. Much of this discussion occurs in the context of “punishment.” Traditionally, there are still people who believe that men are allowed to “beat” their wives or sisters as punishment. This preposterous act of domestic violence should not be tolerated. Although it has been traditionally normalized, it shouldn’t continue to be justified.

We must remember that there are severe, negative ramifications and the contribution of the violence will only continue to hinder our growth as a society.

As Bahadur states, “How colonial officials explained the violence naturally determined what they did to stop it- and what they didn’t do. They didn’t pay women as much as men…nor did officials recruit more women.”

Although “Coolie Woman” is a story about indentured individuals, it reflects the displacement and silencing of women. It is up to a new generation of women to shed light on the bittersweet historical accounts of indentureship while continuing the fight for gender inequality in the Indo-Caribbean community and across the globe.