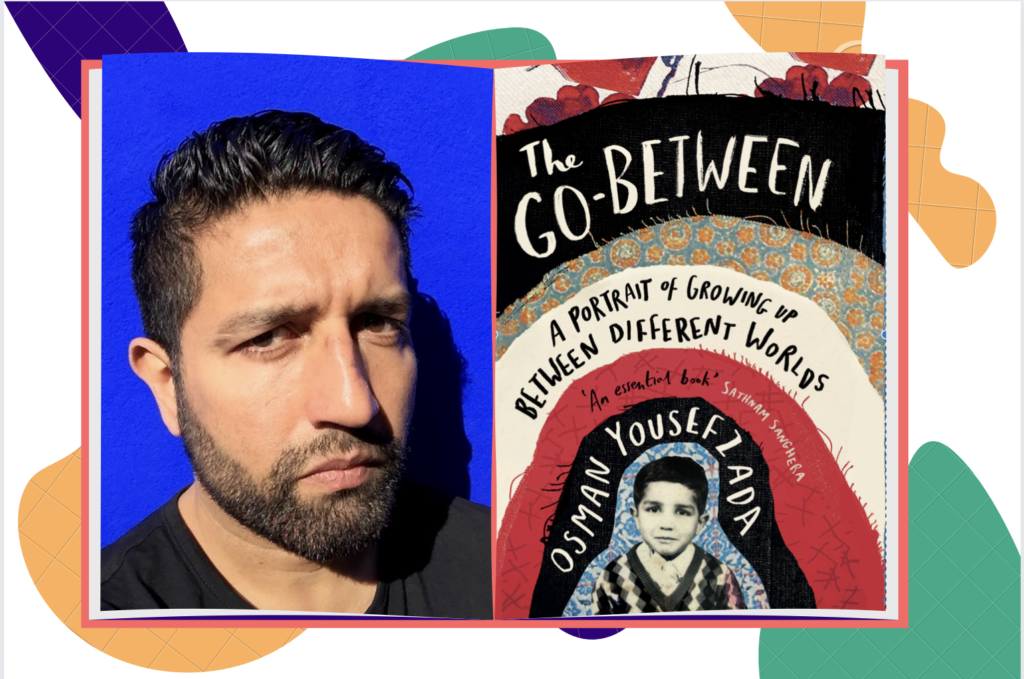

Osman Yousefzada’s “The Go-Between” tells the author’s real-life story — navigating between a Western school life and a strict, devout Pashtun community with clear divides; men versus women, religion versus worldly pleasures and above all else, ‘us’ versus ‘them.’

Set in Birmingham during the 1980s and 1990s, it felt both incredibly surreal and a treat, as a Birmingham resident myself, to read of places I am familiar with and understanding the distinct cultural codes between areas. Like affluent suburb Moseley, with its superior houses, freshly-cut lawns and private park.

I have vivid memories of my cousin, who was part of this ‘higher world,’ getting keys to the park and permitting me into her slice of heaven. I come from the ‘rough’ part of Birmingham, where parks are not private but shared and filled with litter and leftover needles.

Yousefzada’s narrative provides an inviting, story-telling feel, with anecdotes of certain families and characters, that pop in and out. We hear the backstory of certain characters yet also do not get the full details of others; the narrator instead promising that we’ll hear more later and often. Yousefzada’s focus on tiny details shows an importance assigned to these characters that we are also pushed to see as readers. His love for storytelling is deep-rooted throughout his childhood.

The text is filled with humorous moments, yet tinged in tragedy, trauma and frustration. Take for example, young Yousefzada’s struggle with foods that he later finds out contain haram ingredients. I can relate to being told my favourite sweet contains those heart-shattering words — ‘pork gelatine’ —that mean I must give up this special treat.

[Read Related: Brown Girl Like Me: Award-Winning Jaspreet Kaur’s Essential Guidebook on Life as a South Asian Woman]

Interspersed with these moments of relatability are darker themes of domestic violence and misogyny. Reading instances where women are abused by husbands, forbidden to go to school or open doors, unable to take pride in their appearances, wear lipstick and high heels, being solely defined by their status as a wife rather than an individual and are even killed, is hard to read.

The deep-rooted patriarchy Yousefzada describes is suffocating and all-pervading. I cry with the women who have bags of potential but are unable to let the world see them shine like the author’s sisters. My own mother was taken out of school and to this day, talks sadly about her life being stolen and what could have been. Yet, just as Yousefzada’s sisters defy the system to obtain university degrees and establish themselves in the world; my 50-something mother has secured herself GCSEs and is now studying towards a qualification to work with nursery children.

View this post on Instagram

Yousefzada’s desire to reclaim these women and tell their stories is liberating. He points out the warm worlds these women create in the name of female solidarity; where they come together, share tales, air their grievances and comfort one another. Worlds that Yousefzada takes great delight in, before being brutally thrown out of after hitting puberty and resembling the adult male the women are keen to shut out of their female havens.

What I found most difficult, was tracking Yousefzada’s relationship with religion — specifically, Islam. I can identify the characters who use Islam in a self-serving way that thinly veils their hypocrisy in my own life. As a Muslim woman, I hear the words of men around me, who have used Islam as a way to batter and bruise. Yousefzada’s writing demonstrates the importance of teaching children that religion revolves around compassion rather than piling up good deeds or depriving your life of anything enjoyable to fast-track your way to heaven.

My understanding of Islam, is it affords women many rights and bestows upon them a noble status, which the aggressive men that Yousefzada describes fail to recognise. For this reason, I shudder at his description of an Islam used to fearmonger, suffocate women and herald men. I am unsure whether Yousefzada’s portrayal of Islam is for the deliberate purpose of signifying how people distort religion into something it is not intended to be, or if he in fact believes this is what Islam is.

I reached out to Yousefzada’s agent, to hear about his relationship with Islam now as an adult and received the following response:

“still consider myself a Muslim… and have an affinity to ritual…. But seen an expanded culture… being in Pakistan at the moment. With many conversations and many colourings of Islam… which I find more varied and less binary”.

I thoroughly enjoyed Yousefzada’s refusal to portray communities as homogenous. As we hear about the pain women endure at the hands of an oppressive patriarchal system, we also hear of independent female figures who appear freer and more daring. As we hear about tyrannical men who overpower their wives, we also hear of men who treat their relationships more equally.

Yousefzada’s portrayal of women’s oppression at the hands of violent men and a fierce patriarchal system is valid and important but things are more complicated than this binary, which as he suggests earlier, is not helpful or attractive.

[Read Related: The Aftermath of Losing my Mother: A Daughter’s Story]

Just as Yousefzada refuses to paint a monolith, he shows a certain sympathy towards the migrant community who isolate themselves from the West and look inwards for safety, due to a strong belief they will never be accepted by the outside as they are. We hear of settlers reminiscing of their journeys to Britain in the 1960s, where they were exploited and faced racism at work and by greedy landlords.

Fearing this treatment and lacking the tools to navigate such a new space, these men chose separation in an attempt to preserve themselves. Yousefzada tells of new generations of British-born teenagers, who also struggle with violence and discrimination at the hands of ‘Neo-Nazis’ and skinheads. We hear the infamous words of Enoch Powell’s “Rivers of Blood” speech that fuelled race riots and further hatred.

Consequently, that early settler’s fear becomes palpable and reasonable. Though of course, this solitary safety the migrant community crave will not last, as their children are keen to establish themselves as legitimate British citizens, with the right to claim their space in the new, changing world.

Crucially, also, as Yousefzada makes his end point with, a new generation of women have “found their own keys to the outside world” and are forcing the world to see them shine.