by Vaidehi Mujumdar

In collaboration with Trisha Sakhuja

Females “Treated Worse Than Animals” at Mental Health Institutions in India:

A new report, published by the New York-based international advocacy group, Human Rights Watch, depicts a sad and unfortunate picture of the routine abuse female patients with pyschosocial disabilities face at mental institutions in India.

Human Rights Watch researcher Kriti Sharma said the report, “Treated Worse Than Animals,” is based on interviews with more than 250 people on visits to 24 institutions across six Indian cities in four states. The report details overcrowding and lack of hygiene at mental institutions across India, inadequate access to general healthcare, forced treatment – including electroconvulsive therapy – as well as physical, verbal and sexual violence.

Following the 106-page report, a recent article published by the Wall Street Journal India, highlights the deplorable conditions mental health care patients, particularly women, face in India. The systematic abuse along with involuntary medical treatment and violence is just one part of their lives.

According to Rucha Joshi, a psychiatrist at the Thane Mental Hospital in Mumbai, said in an interview with the WSJ, the most challenging part of the patient’s lives is being accepted back into society after they are released.

Populations already vulnerable in society, especially women, often face forceful institutionalizations for mental health issues or disabilities. Even in institutes, resources are scarce and patients are not cared for physically, mentally or emotionally. While the article speaks to a lot of complex social and financial realities of the Indian health care system and society, it’s depiction of mental health stigma specifically for women is certainly not up to date for 21st century standards.

Since India spends 0.06 percent of its health budget on mental care, it only reaffirms why patients at the Thane Mental Hospital, one of four public mental health institutions in all of Maharashtra, sleep on mattresses on the floor, and many staff members present dismissive attitudes toward the patients they conversationally label as “mentally retarded.”

More so, only six psychiatrists staff a hospital with around 1,500 patients.

According to India’s health ministry, matters are just as bad on a national level, since 6 percent to 7 percent of the population suffers from psychosocial disabilities, but there is a shortage of health professionals to meet the demand for care. India has 3,500 psychiatrists, which equates to one for every 343,000 people, according to the World Health Organization.

Now, relate India’s stats to that of the he U.S., where we have one healthcare professional for every 12,837 people in need.

Also, it’s no surprise, most of the Indian women at the hospitals are illiterate and come from poor, neglectful families.

Sharma told the WSJ in a statement:

Women and girls with disabilities are dumped in institutions by their family members or police in part because the government is failing to provide appropriate support and services.”

One such example mentioned in the report was of a 46-year-old woman in Mumbai, who said she was forcibly institutionalized in 2004 at a private hospital for more than a month, where she was treated with electroschock therapy, a process in which electric currents pass the brain. She said her husband committed her to the hospital to prove she was mentally ill in divorce court.

“If I said a single word, he would threaten to put me back there,” she said in an interview with Sharma.

A decade later, a court ruled in the woman’s favor, as the jury found no proof of mental illness and did not grant her husband a divorce.

Shanoor Seervai concludes her WSJ piece with an important take-away, made by the Indian government’s former health secretary Keshav Desiraju:

Source: Youtube.comTo be female, poor and sick is a deadly combination, and it’s so common.”

India’s First-Ever Mental Health Care Policy:

Even more appalling than this report is the fact that India unveiled its first-ever mental health policy in October. The policy calls for an increase in funds and training for a higher number of mental health professionals, in an effort to provide accessible and affordable care to those with mental illnesses. In the context of a country that has long ignored mental health, the policy is progressive and sensitive, hoping to remove stigma and poverty as barriers to care.

Union Health Minister Dr. Harsh Vardhan said in a government-issued press release that universal access to mental health care is a specific goal of the government.

“I visited the famous Institute of Mental Health and Hospital in Agra this week in preparation for the launch of the National Mental Health Policy,” the Minister said after launching India’s first-ever mental health policy. “I have promised it fresh funds for modernisation and expansion. Similar funds will be given to all hospitals in the country to enable them to open departments for treating patients in need of psychological and psychiatric healthcare.”

“The bi-directional relationship of mental ill health and poverty is evident in many reports, including the World Disability Report, 2010, that places persons with mental disabilities at the bottom of the pyramid,” he later said. “This alerts us to what could become a health crisis with damaging consequences for society.”

The Stigma of Mental Health Care for South Asians Living in the Diaspora:

Despite how common mental health issues are, they are hidden, especially within the South Asian community living in the Diaspora. It is almost as if we believe the person is their own cause of a mental affliction or ailment. Through that mindset, we perpetuate a culture of silence that is learned early on and ingrained within us, whether we agree with it or not.

In the seventh grade, I remember going to a summer camp and surprisingly heard my white bunkmate openly talk about her eating disorder and how she was working towards overcoming it. I then remembered talking to a South Asian classmate, who showed all the signs of bulimia, struggle to convince me that her symptoms were only due to the “high stress environment.” She then went on to say, “we all have our vices.”

I later watched in college as students of color disproportionately refused to seek out what mental health resources were available on our small campus. We have all watched, listened and remember stories, incidents and times when we looked away from those suffering mentally, as if poor mental health is contagious.

Many of those suffering only receive required help when an “incident” occurs. Actions are taken when they are hospitalized and when it is clear their disease can no longer be hidden.

Suffering, especially mental suffering, creates its own sphere of silence. I have heard family members and friends say mental health issues are due to “weak minds.” Only a weak mind could succumb to such tensions, right? Wrong!

In those statements we create an “otherness” – where mental health issues are for “others” and something to be hidden.

For many immigrants, mental health is sometimes treated as just another hurdle to overcome. While we work to overcome struggles of displacement, immigration, assimilation and language barriers — we forget to listen and care for our loved ones who need us the most but are afraid to voice their concerns, because they fear rejection from their families and society. That is the mentality and the stigma that plagues so many of our communities worldwide – in which even the most educated fall prey to attitudes and actions that hinder those facing mental health challenges.

Mental health in general is a very specific aspect of health – one that cannot be fixed with just one or two sessions with your doctor or an antibiotic prescription. It involves the complexities of the brain, which is an organ we still don’t fully understand and maybe never will.

To improve mental health education and utilization of resources, we must re-learn, destigmatize, and of course create a platform for people to share their experiences and stories. Support, healing and help come in many forms. Empathy is one of many remedies more of us should apply.

When you hear a stories of personal pain or suffering, how do you respond? How do you position yourself to be comfortable with the uncomfortable?

Prominent essayist and author of “The Empathy Exams,” Leslie Jamison, recently spoke at Columbia University Medical Center’s Narrative Medicine Rounds, where she defined empathy as a function of choice. According to Jamison, empathy is something we make rather than something we feel or inherently know.

The report mentioned above highlights stats and stories that may surprise us, but is a common occurrence in the state of mental health around the world. If empathy is an act, then how do we as healthcare professionals, advocates, writers, policymakers and people work to destigmatize mental health, and further provide resources and education to the most vulnerable of populations?

That question, I believe, is the crux of reducing stigma, aligning allies and garnering resources to advocate for mental health, so that all mental health patients are treated with dignity and respect.

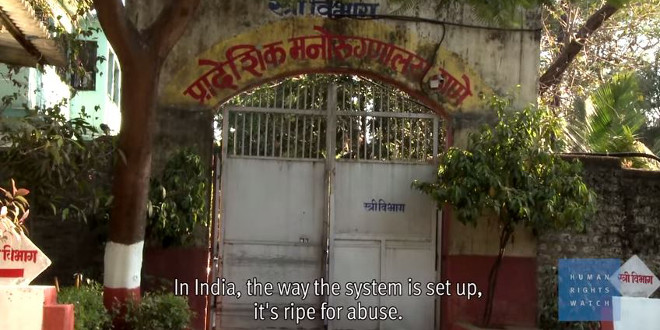

Feature Image: Screenshot from the documentary”Women Institutionalized Against their Will in India,” by the Human Rights Watch advocacy group (Source: http://ow.ly/FH3cI)

Vaidehi Mujumdar is an aspiring physician, writer, and researcher based in Washington DC. She’s a contributing writer for India.com’s US Edition. Her work has been published in The Guardian, The Feminist Wire, Media Diversified, and others. See more of Vaidehi’s work on her website.