The stories that we remember as a society—particularly as a South Asian global diasporic community connected across countless borders and boundaries—are most often stories of success. This success may be attributed to one’s financial prosperity, or even beauty, fame, and unfortunately, going viral. However, we are not all vain. We also remember those who fought adversity; those who conquered significant challenges to thrive; and those who initially failed, yet eventually prevailed. While every migrant or second-generation narrative has its allure, Sanchita Balachandran’s name shines through in the list of South Asian American success stories as a woman who has thrived in a non-conformist field, a domain that tops every aunty’s fear factor list – the arts.

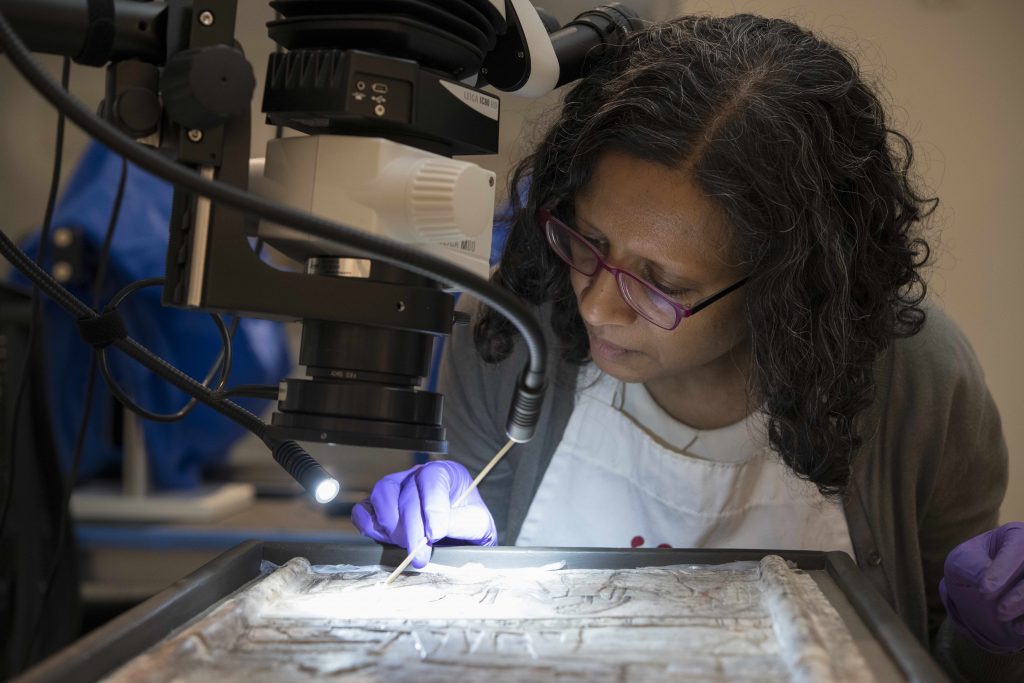

Sanchita Balachandran is Associate Director and Conservator of the Johns Hopkins Archaeological Museum and Senior Lecturer at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland. She makes key decisions associated with conserving and exhibiting elements of history through the preservation of ancient objects, specifically, artifacts from ancient Greece, Rome, Egypt, the ancient Near East, and the ancient Americas.

For those who are unfamiliar with the field of conservation, Balachandran’s work entails the technical and physical process of preserving and studying objects, and the histories of the people who made and used them. While the average person often dismisses the importance of museums, history, archives, and preservation, people like Balachandran sit at the juncture of memory making and remembrance that will influence the understanding, perception, and knowledge of the history of humanity to upcoming generations. Balachandran hopes that her work has the ability to bring these histories and heritages to life for others to witness as well as connect.

[Read Related: Starting Over in Your Career Doesn’t Always Have it to be Bad Thing]

As a South Asian community, we may place extensive emphasis on fields related to medical, engineering and law, but in her position, Balachandran is quietly making waves every day by reshaping the thought process of a field that has often been considered too rigid and colonialist by some critics. Balachandran believes that conservation should be seen as a social process, a field that is about the people whose lives are inscribed on these objects. She states, “Part of what I am trying to do is to think about our field within a broader range of cultural, social and political practices.”

We have all heard the phrase “history is written by the victors,” and museums have certainly acquired a reputation as the cataclysmic representation of colonialism – although not all museums can be seen through this lens and there are many exceptions.

I mean most Indians have matured hearing the story of how India’s colonial oppressor, Britain, unfairly stole India’s Kohinoor diamond, and now displays this preciously sought-after jewel at the Tower of London. This is the injustice that all Nanis and Daadis, Ammoomas and Muthassis sigh deeply about, whether there is more to the narrative or not. Various museums are also pushing these boundaries or acknowledging their problematic past. However, Balachandran had never dreamed about changing the field, let alone entering it, she was on the way to become the model South Asian American citizen. She was preparing to become a doctor and busy taking science courses in college when a few art history courses changed her fate.

Balachandran remembers telling her mother about her intentions to shift career paths on the highway and laughs recalling that her mother almost crashed the car.

“Don’t do this on the highway!” she humorously warned.

Balachandran certainly felt the pressure of diverging from a path that the South Asian community was devoted to following, and yet her family became her greatest source of strength. She still remembers phoning her father and telling him that she had to go to graduate school in art conservation. He replied, “Then you should do it.” While she may have felt uneasy and scared about telling her family at the beginning, they became her greatest network of support. Balachandran touts the supportive structure of the South Asian extended family that can nurture and foster individuals to embrace their best talents and bring them forward. She explicates that her family’s assistance cannot be overlooked in helping her achieve her goals – they were with her every step of the way.

In 2009, Balachandran won a Fulbright Award through the United States-India Educational Foundation and had the opportunity to conduct research on the history of conservation in India. She explains that after spending some time at the Government Museum Archives in Chennai, she saw a name that was familiar, it was her grandfather. She learned that in the 1930s and ’40s, he had been completing the same research work that she was now conducting. If she had still held any reservations about her career, it was this moment when she recognized and accepted that this path truly formed into her destiny.

As a young girl, Balachandran traveled back and forth between India and the United States with her mother who held a prominent position with the Tourism Department of the Government of India. If she saw an Indian collection such as a statue of Lord Ganesh, she would get excited and run towards it – I would argue that this is why representation is imperative. Balachandran explains that seeing your culture and your people reflected in these artifacts held a significant meaning for her as a child, it somehow symbolized that your people mattered – which rings true for adults as well. While speaking to her, she asked me if I recalled that scene from Black Panther where N’Jadaka walks in this ‘white cube’ style museum, and then a white woman enters and tells him about his culture. She explained how that scene represented the problem with how museums once worked and how they were perceived by the public, but of course, that is changing. Moreover, her work allows her to see a different side of museums, which are so much more than a distant white cube.

“I think what I find meaningful about my work is that it is possible for us as humans, in general, to feel more connected to the people of the past – that we see linkages between past cultures and people who were very different from us, and separated in time and space, and yet yearned for some of the same things: Care and love of our families, acknowledgment of a life well lived, joy in the beautiful and functional things around us, security, safety, etc,” she said.

As progressive and enticing as Balachandran’s views or journey may be, her personality and achievements are equally remarkable. Her friendly demeanor and passion for conservation contain no hint of her position’s distinctness. Her humble attitude is another reflection of the ideals that she believes are necessary to adopt in her field. As one of her most memorable experiences, Balachandran lists the preservation of a 2,400-year-old Egyptian woman, now named the “Goucher mummy” whose remains she conserved, and whose face she was able to recently see for the first time through an interdisciplinary research project. She describes this as an extraordinary experience in which she handled and cared for the remains of a woman from centuries ago. For her, these acts of preservation have highlighted an aspect of humanity that extends across perceptible differences and ties people together as one human race. She states that her work eclipses divisions and connects humans across time and space.

In addition, Balachandran is a South Asian woman who works in a field with a limited representation by people of color, this is genuinely a significant achievement. In terms of representation, voice, and multivocality, Balachandran’s success holds social, political, and cultural implications for all of us as a community. She indicates that her positionality as a South Asian American woman in addition to an array of identities and life experiences allows her to adopt an innovative approach and ask questions that have not been asked before. Furthermore, Balachandran remembers how she rarely saw any South Asian sheroes growing up and felt a lack of representation. When she played superheroes as a child, being the youngest and last to pick, she was always left acting like Aquaman. However, this did not mean that there were no South Asian sheroes, it simply took her time to recognize them. Recently, her five-year-old daughter made her a card with a superhero figure, and since the face was colored in brown, Balachandran asked her who the superhero was, and she replied, “It’s you.” The card depicted Balachandran standing fiercely in a cape. Balachandran began thinking about her past and realized that although South Asian women may not have been exposed to many representations of successful South Asian women, their mothers, aunts, grandmothers, and cousins filled that void.