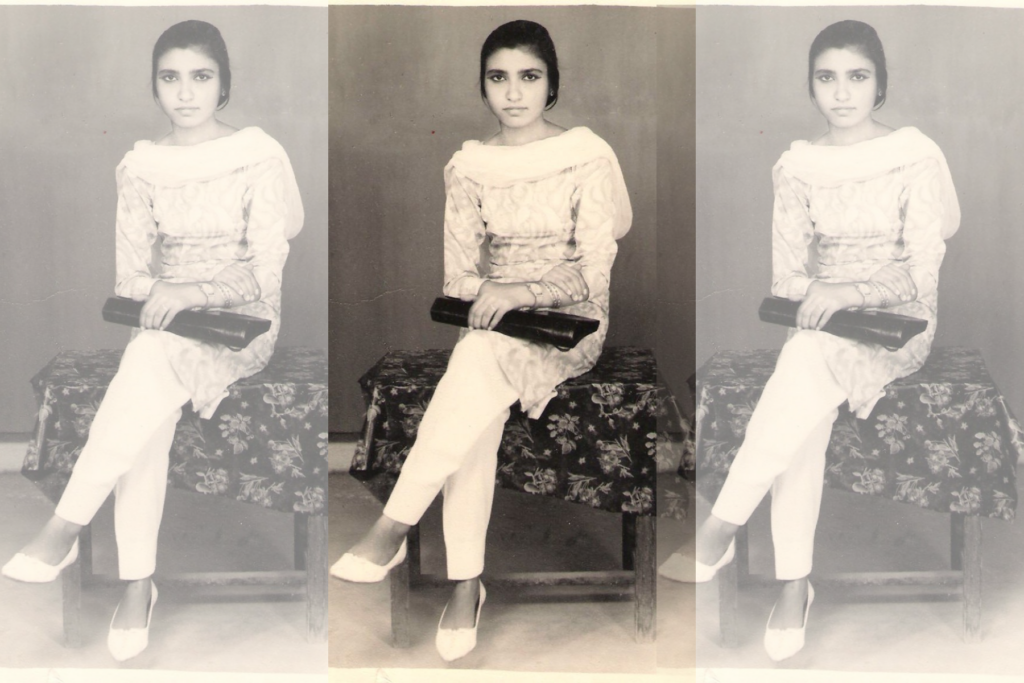

Photo Courtesy: Rakhi Kanwar

It’s been a struggle for two years to write this, but then how do you write a legacy adequate of someone who was your entire home? It’s impossible. This is my Mum. Krishna Kanwar.

I lost her to oesophageal cancer on Nirjal Ekadshi, the eleventh day of the waxing moon in June 2019, within the space of one year after she received her diagnosis. I say ‘lost’ because some days the grief feels akin to the panic you may have felt as a kid if you’d ever strayed away from your parents in a supermarket and you suddenly realise you can’t find them. ‘Lost’ because grief detaches, destabilises and disorientates you as if an imperceptible film has formed between you and the rest of the world. ‘Lost’ because despite all the spirituality you may have been brought up with, you start questioning where they are now and if they’re ok (are they OK? Please God let them be OK); and ‘lost’ because where do you place all the love you have for a person when they’re gone? It’s said that when you pass away on Nirjal Ekadshi, you attain ‘moksha’ and become liberated from the cycle of birth, death and rebirth. I can believe that. She had the strongest faith and purest heart of anyone I’ve ever known.

So yes, I lost my Mum. My Mum, who was always more worried about me than she was about herself, even during her illness, getting up at the crack of dawn and making boxes full of panjeeri (whole wheat flour, nuts and seeds, cooked in sugar and ghee and rolled into balls, and probably the original ‘energy ball’) and matthi (the flakiest, fried wheat biscuits seasoned with carom seeds and black pepper) for me, who would massage warmed coconut oil into my hair and onto my back when I was stressed during exams despite her osteoarthritis, who would bring me jewel encrusted kangan (bangles) back from every visit to India as she didn’t like my wrists being empty. My Mum, who gave me the opportunity to experience the entire world (even if often begrudgingly, out of concern) that she was curious about but didn’t savour herself.

My Mum grew up in Punjab and in the foothills of Shimla. Incredibly bright and creative, she skipped three years of school and completed a Master’s in English and Politics at Punjab University before immigrating to the UK to marry my Dad whom she had never met before, but had exchanged long letters on blue airmail paper with.

Perpetually inquisitive, she brimmed with so much general, historical and theological knowledge that we’d joke that she was an oracle. At her core, she was a teacher and taught us all so much. The beauty of languages. Soft-spoken Punjabi, unless she was angry and then it turned sharply into ‘Fitteh moo there!’ (the literal translation is ‘sour face,’ but it’s a verbal form of facepalm), and to read and write in Hindi (she set up her own Hindi school in the ’80s and mentored my brother and me through our GCSE Hindi). The drape of Indian clothes, elegantly tying a Banarasi silk sari a hundred different ways (representing all the cities of India) on me before choosing her favourite, with each pleat immaculately folded. To swim and love the water, learning herself when she came to the UK just so that she could take my brothers and me.

[Read Related: How my Nani Overcame Racism in the U.K. Through Resiliency and Courage]

The essence of our culture, stories from various Hindu scriptures and Sanskrit mantras, explaining the meanings, dissecting and translating each word. And to cook (which I only fell in love with two decades later) with the influence of Ayurveda. ‘What will you cook for your children?’ she’d say when I always rebelled against what I considered patriarchal traditions. ‘He can do the cooking, I’ll marry a chef,’ I’d typically respond. (Although I’m now filled with the regret of not writing every single recipe down.)

She would, quite often, be called to our primary school when either of my brothers or I got into fights (where usually we had only acted in self-defence). It was the ’80s, and we were the only browns in our schools. It could be pretty racist (slurs such as ‘blackie’ or ‘Paki’ leaving us confused and trying to explain that errr we’re Indian so if you’re going to insult us, at least get the country right and usually culminating in my brother, Ashu, pulling the hair of some girl who had sworn at me or punching a boy who had hit him). Fiercely protective of us, like Raksha, the mother wolf, and always in our corner, my Mum would respond to our teachers’ allegations in immaculate English, ‘Yes, but who hit who first? My kid did not throw the first punch. I told my kids to stand up for themselves.’ She’d then return to the car where we waited and gleefully say with such pride, ‘I told that teacher of yours off. She was a bit badtameez (bad mannered).’

My Mum was genuinely so loved. She had a humility that warmed and attracted people around her, an authority and wisdom that everyone in our extended family respected and was constantly seeking counsel from, not making a decision without consulting her first, and an aura and playfulness that enchanted an entire room. At wedding sangeets or pre-wedding-parties she would wrap a dupatta (scarf) around her head and pretend she was a male farmer in Punjab, growing and getting higher and higher on bhang aka cannabis while everyone around her screamed, ‘Shava!’ in hysterics. She was the matriarch to and the mesh that bound our entire extended family.

She had a natural interest in spirituality and a thirst for knowledge that I inherited. Like so many of the other things I inherited from her, her legs, her sense of humour, her creativity and drama. Her sensitivity, her contradictory force and vulnerability. Even her temper.

Our relationship wasn’t perfect. She often couldn’t understand my carefree nature and I often didn’t understand the root of her concern in relation to it. I rebelled against, amongst other things, the tropes of South Asian women sacrificing and surrendering that she would instead see as a selfless labour of love. I wish I had realised then, that she was just from a different time and understood better the experiences of their generation, in particular the women who had immigrated to this country.

Nothing prepares you for grief, no amount of meditation, no scriptures, when you’re personally hit with the fragility and impermanence of your most loved one, the unfairness and illogic of illness, suffering and death. And that’s exactly how grief feels, like you’re being hit chaotically and constantly in waves. Unannounced. At random. When you least expect. Everywhere. On the tube. At yoga. In a shop. In your sleep. When you recognise that some of your own habits come from them. That split second when you reach to call them to ask them how much besan (gram flour) to add to your kadhi (a dish made of slow-cooked, slightly soured yoghurt and gram flour, seasoned with coriander, fenugreek and mustard seeds and topped with potato and spinach fritters), but then reality suddenly hits that they’re not there (remembering and ‘re-losing’ them all over again). I know she’d just say, ‘andhaje dhe naal’ (a gut estimation/judgment that comes with experience) in any case.

I miss everything. Watching Disney movies together. Sitting on her bed while she modelled all the clothes she bought with my chachis (aunts) but was waiting for my opinion on, ‘Rakhan ke naah rakhan?’(‘Shall I keep it, or not keep it?’) Her singing nursery rhymes to my niece and nephews. Her leaving voicemails on my phone saying ‘Onne phone nahi chukiya,’ (‘She didn’t pick up her phone’) or calling me to say, ‘Ki khaan noo ji karda?’ (‘What do you feel like eating?’) when I was coming home and sarcastically, ‘Tera bela hogeya?’ (‘Could you have taken any longer?’) when I was late. Her scent when we’d lie in her bed and giggle and my Dad would come upstairs and ask us what we were gossiping about. Her calling me in early December to remind me to buy my own present so that she could wrap it and give it to me on Xmas day. How she’d tell me I had the ferocity of a ‘babar sher’ (lioness) when we disagreed on something (which was often). Buying a single set of payals (anklets) and then walking around the house in one each, mine always sliding off my skinny ankles, prompting her to complain ‘put some weight on, you were so much cuter when you lived in this house, round and fat, gol mol moo sigha tera, like the moon.’ The taste of her food, crispy, thin aloo vale parante (flatbread stuffed with masala spiced mash potato, chillies, coriander and onions) dripping with butter and served with homemade yoghurt.

Most of all, I miss just holding her hand (and my God, every day I wish I had a time machine to do just that). Rest in peace Mama and rest in power. Love you. x