**Trigger Warning: Mental Health, Suicide**

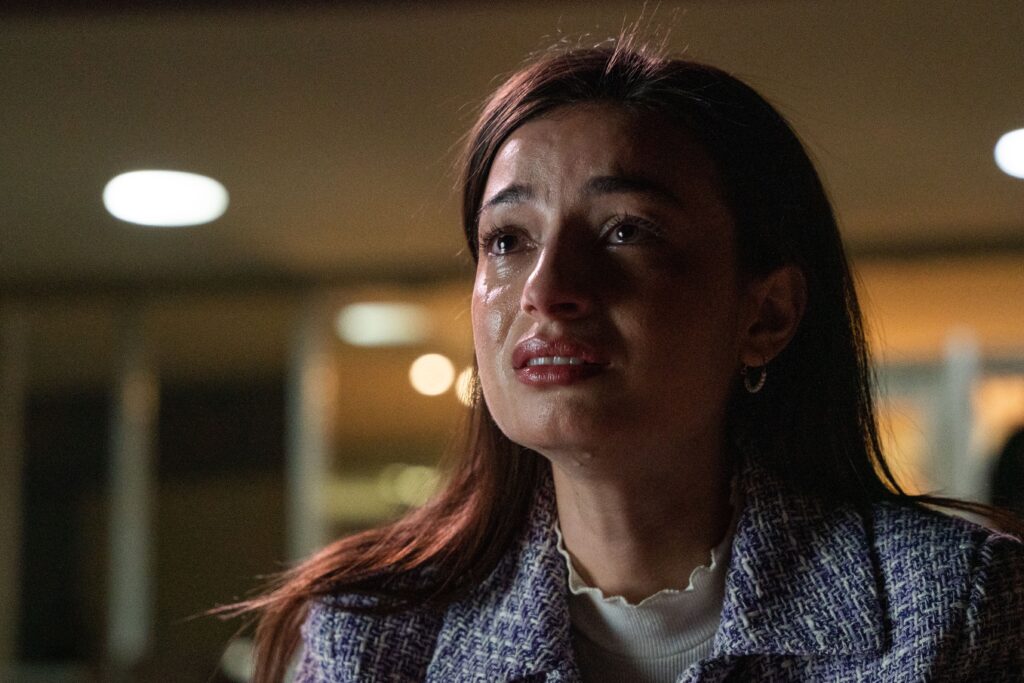

Aisha (Sana Asad) is a high-functioning, Type A individual with a checklist to manage just about everything. She’s a great friend, a supportive girlfriend, a responsible daughter and a good student. Yet it’s her final year thesis that’s somehow become the bane of her existence — she just can’t get herself to work on it. The reality of her struggle though is beyond academics. Behind all the perfectionism that is seemingly chipping away her closest bonds is her battle with depression; depression that pushed her to almost take her own life; depression that she very naively attempts to “fix” with yet another checklist.

“Get Up Aisha” may give you the ’90s sitcom feel with its college life, single parenting backdrop and funny one-liners, but the agenda is very clear: there is no one face, one persona, one culture, one religion, or better yet, one cause to mental health. You could be a high achiever and/or a devout Muslim and still struggle with mental health issues. The series deftly throws light on the challenges of living with depression while debunking South Asian stereotypes. Aisha’s mom (Zarqa Nawaz) is a single mother who isn’t really the cultural role model we are used to seeing in the South Asian community and that in itself is such a breath of fresh air to be able to watch on screen — the fact that every human being is flawed and struggling with their own demons.

The protagonist in “Get Up Aisha” is also a refreshing change from common depictions of depressive individuals. Aisha has good and bad days, Aisha is happy and chirpy and yet confused of her outbursts, struggling to make sense of her mental chaos — a very normal trajectory of an individual’s journey with mental health that we don’t get to see on screen as often. Sure, there maybe moments where you feel that the pace of the series is rushed, but it doesn’t falter in developing and adding a dimension to each of the characters, and it most definitely doesn’t fail in achieving it’s purpose of getting the community to talk. What is also remarkable about “Get Up Aisha” is how it ends, showing rebuilding and healing to be a process and one that is non-linear. There are no solutions. Everything won’t always be hunky dory; life will never stop throwing harsh outcomes towards you, and you just have to keep working on yourself regardless.

We sat down with the three makers of this poignant, much-needed story — Rabiya Mansoor, Nisha Khan and Marushka Jessica Almeida — to discuss their motivations behind developing the series and the journey of getting the project finally off the ground.

This interview has been edited and condensed for brevity.

What inspired and motivated you to make “Get Up Aisha.” Why was it so crucial for all three of you to explore mental health within the South Asian community and develop into this series you’ve created?

Mansoor: We really wanted to make a show that focused on mental health in the South Asian community because it is, unfortunately, still a taboo subject. This whole idea of ‘what will people say’ is still so prevalent, and all three of us have similar experiences [relating to it]. Even though our parents are different, they all still center on that aspect of ‘it’s okay, if you go to therapy, but maybe you shouldn’t tell other people because we don’t know what they’re gonna think of you.’ And so, we wanted to create a show that could start conversations within the wider community even though it’s funny and has these dramatic moments. For us, that’s really the central idea behind “Get Up Aisha.” that. It’s not just something we created as a piece of art, but also as a piece for the community to come around; for parents to check in on their teenagers, for maybe the adult children to check in on their parents.

Tell us about any personal experiences that you all drew from when writing the story and those that motivated you to embark on this journey.

Almeida: All of us have dealt with mental health and depression in different ways. But I think the thing that united all of our experiences was having Type A traits — like no matter what we were going through, we always had this drive to just achieve and be successful and hide it from other people. That aspect is prevalent in all of our stories. Often when we see depression depicted on screen, it’s usually a very sad girl crying alone in a room which is very normal. But it’s one face of depression. But the one that we all related to, when we’re also talking to more people, was a type A version of it, where you feel the need to put it on the back-burner and still go to your job, get good grades and do all that needs to be done. And I think that’s what mirrored all of our experiences.

Mansoor: Depression is something I’ve struggled with since I was 15-16 years old. And one of the things that I’ve always tried to reconcile is my parents approach to it because my dad also struggled with depression. And I have people in my greater family, like aunts, cousins, who have also dealt with depression. So it is quite prevalent in my family. I even had to take a semester off from Law School. But even then, while my parents understood it and supported therapy, they were like, ‘Oh, don’t tell people that you’re taking a semester off, like, just tell them you’re taking online classes and stuff. So there were two parts to it; while my parents were supportive in private, outwardly it would be a bit of a different narrative. And that was something that created a lot of confusion in me and instilled some shame around the subject.

Khan: Similar sentiments to what Rabiya is saying; the aspect of not telling your family what’s going on and stuff. And I think throughout the series when you watch Aisha struggle to talk to her boyfriend, struggle to talk to her best friend and to her family, you’re kind of wondering where it’s coming from even though she comes off as really confident. But it’s that level of shame that’s ingrained, especially in our community, where we see ourselves always being judged. If I am honest, it’s not a welcoming place sometimes.

The mom in the series isn’t necessarily the most difficult South Asian mom we are all used to seeing on screen or generally know of. She’s just like another teenager herself, confused, trying to fix things, slacking on chores. Is there a reason why you envisioned the mom’s role to be this way?

Khan: Growing up, our parents wanting the best for us, that notion they say comes from this place of their love not being conditional. Sorry but their love is conditional. If you do these certain things to make me happy, I will love you, I’ll accept you, I’ll be proud of you. And it’s so tough for a child growing up to think that if I do certain things, and if I don’t do certain things, then my parents’ love is actually going to escape from my hands. And it’s a horrible parenting method, obviously, because what ends up happening is, children, they have so much pressure on themselves, they feel like they need to achieve a certain goal post. And all children can’t reach the same goal post, and they shouldn’t be reaching the same goal posts. But what happens is parents are like, ‘well, look, those kids are doing this, you have to also do this. And if you don’t, then I’m going to love you a little less.’

With Fawzia, we purposely made her so that you feel like her love honestly is unconditional, and that she supports Aisha, she cares for Aisha, she just wants Aisha to be happy. And you see that, especially in the end, when she says, ‘you know, I just want you to be happy.’ And that’s something refreshing to be able to hear from a South Asian parent, where it’s not attached to any grade, it’s not attached to how many chores she does, it’s not attached to anything other than her just being herself. And I think that representation and being able to see a parent like that is so important. It shows that in a household, a child will be able to express themselves and value themselves apart from what they can offer, essentially.

Mansoor: I think people feel that this idea of the South Asian mom represented in the show is a bit of a fantasy, but it’s also very real. My parents are very similar to Fawzia. So seeing this depiction of parents, maybe as another representation of South Asian parents is good for our own communities; to see how there are different types and styles of parents out there.

I also wanted to ask about the therapist. Unlike in Hollywood series where therapists are usually these very serious, polished, and uptight individuals, in Get Up, Aisha, the therapist is a very normal, ordinary looking individual that you would stumble across on the street. Was there a thought that went into shaping this character at all?

Almeida: It was definitely very intentional for us that we wanted someone who you felt could be your neighbor, who you felt like you could know. When we think of therapists, because of just by the nature of their profession, we think that they have it all together, right? Because they have to, otherwise why else are they in this job. But I feel like that’s a bit disingenuous, because they’re human. They’re humans after all, and are still also growing and shaping as they work. So I think we want really wanted to show someone who was like a very regular person, who that you could feel comfortable going up to, and talking to and sharing things that are really intimate and really personal about your life. And I think that Ann Pournelle, who plays Alice, really, really embodied that. She killed it in just one take because she was that good.

How has the journey been like for you all; getting this project off the ground and finally getting streaming rights with CBC as three BIPOC creators? What were some of the challenges you faced and learnings of the process?

Mansoor: Yes, it’s been a challenge in terms of putting the financing together and being producers doing this for the first time on such a scale. But Marushka and I are actually like gender nonconforming, and that gender aspect, played heavily into a lot of different things. When we were on set, being the bosses on set, and in terms of how much people would listen to us, or just certain things that were said, or certain questions that were asked, we felt like if we were men, in this position of authority, would we have been treated the same way? And a lot of the times we were probably not. Because it was our first project on this scale, people thought that our inexperience will allow them to get away with things and they tried to slide things past us. So I think that was a challenge.

Getting a broadcaster on board was also another challenge. CBC gem is interesting in the sense that when people hear that our show’s on CBC gem, they think that’s very exciting and it 100% is but they gave us basically no money. We had to go raise the money elsewhere ourselves through applying for different funds available here in Canada. And a lot of sweat, blood and tears went into getting all the financing together for this. So, also being kind of exposed to the realities of what it’s like to create content here in Canada, it was an important lesson for us and a bit of a wake up call that if we want to be telling these stories, we have to be the ones on the ground, putting the money together, knocking on those doors, and just being the creative sometimes isn’t enough. So yeah, it’s just been a huge learning curve on all fronts. But the best part has definitely been working with Marushka and Nisha, and excited to continue working with them on future projects as well.

What do you want the audience to take away from this? Like, what’s the ultimate goal? I know we’ve discussed that you wanted to do this because you wanted to start a conversation in the community but say after somebody’s done watching the series, what is the thought that you want them to leave with.

Khan: I think for me, I hope the thought that they get left with is, depending on especially the dynamics of their family or their friends, just seeing that clearly as we see Ayesha struggle throughout the whole series of not being able to open up, and then seeing the sort of release in the last episode, and what that can actually give a person; give them some peace and clarity. And so, it would be nice that if someone were to walk away watching it, they would feel a little bit more empowered to be able to discuss their own feelings and their own issues and feel confident and talking to the people around them about these things, and realizing that it’s almost like you’re shaking a bottle. And if you just keep it all in and keep your emotions in, the way we’re taught to, i’s kind of the worst thing that you could possibly do. And eventually, what happens when you shake the bottle, it’ll explode, right? So I hope that when people watch that, if they themselves are struggling with opening up, hopefully, they can find the courage to also open up and maybe get help if they need it.

Almeida: I’ll just add that, with any piece of media, like the ultimate hope is just to share stories that resonate with other people, that make them feel seen and make them feel heard, because I think this is a show that I know, when I was really struggling with depression, could have made this difference in my life, showing me that there are other people who are struggling in the same way that I’m struggling; who understand what I’m going through. And ultimately, we just want people to feel they’re not alone in their struggles. There are resources, there’s help for them. And we want to leave people with this message of hope that there is this light at the end of the tunnel; that there is a there is light after there’s dark.

Mansoor: I think they mostly covered it all. But I think the last one that I’d add is that perfectionism is the enemy of good. Throughout the show, we see Aisha strive for something that isn’t real. And I think the pressure that it has, and it builds is really something that is detrimental to living a good happy life. And that’s what I want people to take away from the show is that, that pinnacle doesn’t exist, and it will never make you happy trying to get there. So just live in the now and enjoy the moment and whatever happens, will happen.

“Get Up Aisha” is now available to stream on CBC Gem.