In 2000, my father immigrated to the United States to secure a job and a place for my family to live. He, like millions of other South Asians, moved here in the pursuit of the so-called American dream. While it took our family some time to establish financial and emotional stability, I always had a roof over my head and food on the table. There was nothing standing in my way from attending school, and I had abundant opportunities to go to college, securing a job even before graduation. It’s true that while there have been times I’ve faced racism and microaggressions, my life as an immigrant has been generally comfortable.

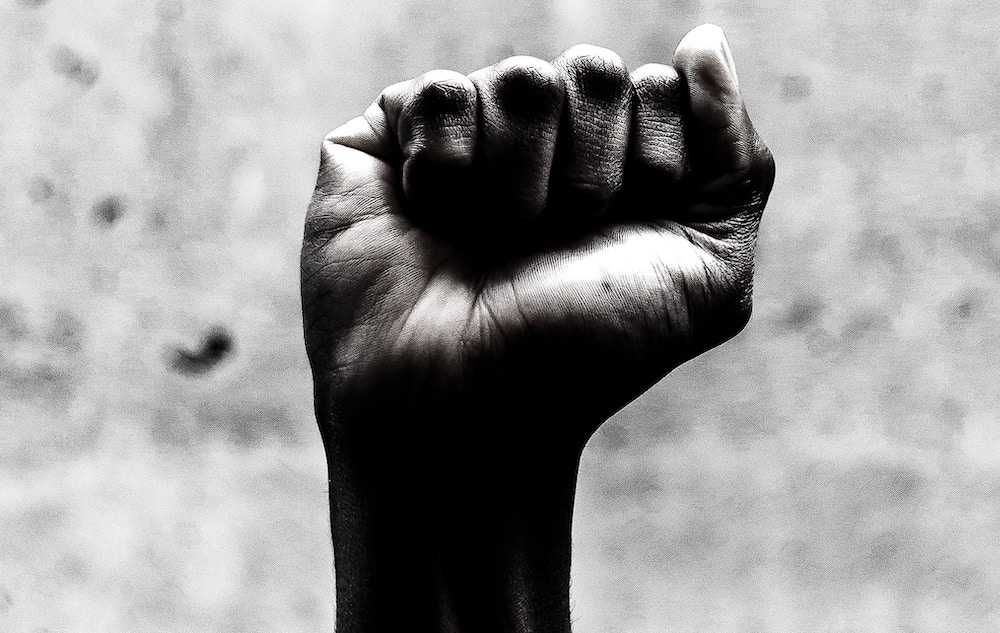

February is Black History Month. And as a desi, I’d be remiss if I didn’t take a moment to reflect about the many African Americans in history, whose contributions and sacrifices paved the way for those not only in the black community but also for other minority groups—for people like my dad, for people like me.

The Story of South Asian American Success

According to the Pew Research Center, Asian and South Asian populations are among the fastest growing racial groups in the United States today, well on track to become the country’s largest immigrant group. About half of all Asians older than 25 have a bachelor’s degree or more, with Indian Americans leading the pack as the most educated Asian immigrant group. As of 2015, the median income for Indian Americans was $100,000, almost twice that of the national median income of $53,600.

Suffice it to say, the American dream is within reach for brown immigrants, and our communities are reaping the fruit of success. But we didn’t find such success simply by pulling ourselves up by our bootstraps. South Asian Americans owe more to the black community than we’ve ever given them credit for. But the truth is our contemporary successes can be traced back to the civil rights movements of the 1950s and ‘60s. It was the marches and nonviolent protests of black leaders like Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Rosa Parks, and Bayard Rustin that led to laws allowing for South Asian Americans, and particularly Indian Americans, to flourish.

Early Immigration, Long-Lasting Racism

While South Asians have been in the United States since the 1700s, the first notable wave of immigration occurred in the late 1800s with groups of farm laborers. In the following decades, more migrants, primarily Punjabi Sikhs, would settle down on the West coast as railway workers.

As more immigrants moved in, anti-Asian sentiment grew, Following the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, racism reached a peak with the Immigration Act of 1917, also called the Asiatic Barred Zone Act. This new law restricted the immigration of “undesirables” from other countries, including those in the Indian subcontinent.

It also imposed a mandatory literacy test for those who are 16 and older. In an attempt to further limit immigration, Congress passed the Immigration Act of 1924, which created immigration quotas for each country and banned immigration from Asian countries altogether. The decision in the 1923 Supreme Court case United States v. Bhagat Singh Thind further stripped South Asians of their rights, ruling that they were not “Caucasian” and therefore couldn’t own land or be eligible for citizenship. Subsequently, South Asians in the United States faced segregation, employment limitations, and were generally treated as lower-class citizens for decades.

Gains for South Asians After the Civil Rights Movement

The model minority archetype grew from these laws and other national concerns of the times. Asian immigrants began to spread stories of how their families upheld tradition and had well-behaved children. These stories were meant to portray them as upstanding citizens who were fully assimilated into American societies. As historian and author of “The Color of Success” Ellen Wu says, they were more than a “survival strategy.”

Even as overt acts of racism seemed to decline, racist and discriminatory laws still held South Asians back from progressing in society. Voting restrictions, literacy tests, and housing discrimination were still legal. The persistent campaigns and struggles of African American civil rights leaders finally resulted in sweeping legislation for all racial minority groups: The Civil Rights Acts of 1957 and 1964 and The Voting Rights Act of 1965. Promising equal employment opportunities and voting rights for all Americans regardless of race, the laws allowed South Asian immigrants a path to stable employment and civic involvement.

[READ RELATED: 7 Black Activists You Should Know and Their Solidarity with the South Asian Resistance]

The movement also shed light on the discriminatory policy of immigration quotas, which led to the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965. While the law didn’t abolish quotas altogether, it replaced them with a system that preferred relatives of current citizens, refugees, and immigrants with professional skills.

Over 12,000 Indian immigrants moved to the States after this law was passed. Due to the preference for skilled workers, most were typically of higher castes and came from middle-class backgrounds. The assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. and the ensuing riots pressured the government to pass the Fair Housing Act of 1968, further benefiting South Asian immigrants, as they, too, had a path to home ownership. Because they also faced less housing discrimination than their black peers, these South Asian groups were able to start their lives in middle-class neighborhoods with access to better education. This effect compounded through the subsequent waves of immigration over the next 50 years.

Fast forward to the latter half of the 20th century, and South Asian immigrants are among the most well educated and successful in the United States, holding positions of power in nearly every employment sector.

The Impact of Black History on the Future of South Asians

Though our communities have faced setbacks and been victim to ridicule and racism, there’s no argument that South Asians generally enjoy privileges that our African American brothers and sisters don’t. And much of that is due to the systemic racism that is embedded in our country’s historical and modern social structures.

[READ RELATED: Why I’m Standing in Solidarity with Black Lives Matter as a Brown Activist]

Like me, I know there are many other first-generation South Asian Americans who can identify with this uncomfortable truth. We have parents with well-paying jobs, who own homes, who can afford to pay for higher education, support us financially after college, and set us up for success, so we can do the same for our children. But let’s not forget that we’re able to own land, gain citizenship, participate in government by voting or running for office, and so much more because of black leaders. The foundation for our success was largely built by the people who fought for equal rights for all during the civil rights movement. Our history is intrinsically tied with black history. For this, we must be thankful every month — not just in February.