Photo courtesy of Renluka Maharaj

“…be open to learning about a history that has affected millions of people and has caused generational trauma. I want the viewer to see beyond their eyes and trust themselves to know that the beauty that is so profound in the work is also very complex…” – Renluka Maharaj

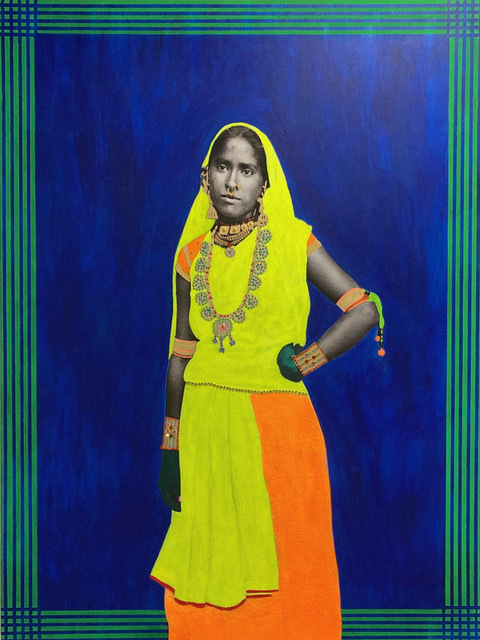

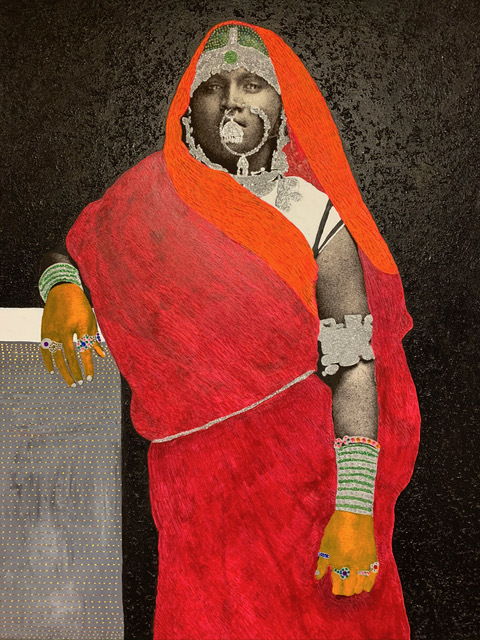

Renluka Maharaj’s list of art supplies reads unlike any other. Beads, glitter and archival photographs of Indian indentured servants, some including her own family, all adorn neon canvasses. A self-described perfectionist, Maharaj often finds herself giving one project her all and fine-tuning its appearance down to the slightest adjustment of a bead.

Beads and glitter can easily be found at the art supply store. However, she unearthed the photos from her family albums and the archives of French photographer Felix Morin. Morin’s images captured Indian indentured women in Trinidad and Tobago. These were then printed across postcards in order to market the location for future colonial use.

[Read Related: Traveling Indo-Caribbean Mural Spreads Message of Women’s Empowerment]

The Indo-Trinidadian artist is based in Colorado and travels to New York and Trinidad often. Her Caribbean motifs of vibrant color schemes, heavy embellishments and regional ties to colonialism, demonstrate the deeply rooted connection that her upbringing has had on her artistry.

From confronting sexuality through androgynous representation to illustrating the injustices committed against the multitude of Brown women she finds herself akin to, Maharaj proves herself to be as daring as the pieces she puts together. She demonstrates her multidisciplinary role as an artist by hopscotching from abstract painting to black and white photography and a variety of mediums.

“I don’t see how I could be pigeon-holed unless the art gods decided I was not worthy enough somehow, but it would be their loss,” shares Maharaj.

Spectators should pay attention to the titles she uses for her collections and individual pieces, as they are methodic and tend to reference something of particular importance and substance in the sphere of Indian culture. Think “mangoes” and “gold”—crops of the Caribbean that Maharaj weaves into her art for heightened meaning beyond what you see.

In our socially distanced interview, Maharaj answered my questions from Boulder, CO.

Within the last several years, your work has been featured in roughly 30 exhibitions nationwide. Can you speak to the three new exhibits you’ve just landed and what we’ll see within them?

“My work continues to evolve, at least aesthetically, but the narrative is the same. How often do I get to see someone that looks like me in museums, or galleries, or even TV? It’s rare and it’s one of the reasons I became an artist. I believe representation is very important to our mental health and I will continue my discussions around this subject of indentureship. I want as many people as possible to know about this movement of millions of East Indians around the globe and the total disregard for their lives in the pursuit of upholding a system of capitalism.”

Coming from a very small pool of Indo-Caribbean artists, did you ever feel the lack of widespread representation hurt your ability to create?

“It has been the impetus for me to create. What hurts is that lack of representation and having to school most people I meet about this history because it has not been given the attention it deserves.”

The arts typically isn’t the area Indo-Caribbean individuals pursue. What did your family think of your entry into this world and were they supportive?

“My mom—who is no longer with us—would not approve because immigrant parents want us to make money, establish ourselves, buy a house, raise a family and those are great things because it creates stability and security, but I needed something outside of that box. My family overall is supportive, but I think they would have liked it better if I were a lawyer or something more practical; it’s what most people would identify as successful.”

Plenty of your work draws from your personal history and culture. When you aren’t finding inspiration through that, where do you look for inspiration?

“My mind is always at work and inspiration can come from anywhere. I look at a lot of art from around the world. My favorite painters are Spanish and French and often looking at their paintings will give me ideas on composition, color and texture. I prefer reading Caribbean writers (predominantly from Trinidad) as it feeds ideas around symbology or titling of the work or gives me an overall feeling of being at ‘home.’ Since I cannot travel right now, it’s the closest I will get to being there.”

How has the pandemic changed the way you create art, if at all?

“It has made me reconsider materials because of the lack of funds right now. With shows comes the responsibility of producing and that costs money. I have to think about size and weight, so shipping can be more cost efficient. Also, with a lot of added time, I am doing more research and have found communities online for the first time that have been a great help to my concepts.”

How is sexuality displayed in your work and what is your stance on it?

“Sexuality is such a taboo topic, especially in regard to women. Early on, sexuality played a more dominant part of [my] work as seen in the Epicene series. But I have slowly moved away from the obvious to the more subtle expressions of this idea. Sexuality is diverse and personal. I support that.”

Your pieces showcase icons that Indo-Caribbeans are familiar with, but socioeconomic factors prevent them from being your customer base. Due to this, do you think your art ever risks being appropriated?

“I am trying to figure out a way to make my pieces available for a broader audience because it’s important to me [that] these images find homes where they can be appreciated. I find it bothersome that only rich—mostly white—art collectors get to have amazing art around them. Yes, there are a lot of moving parts and I have to figure out a way to have it work for me that’s respectful and dignified and also allows me to continue working. We can’t avoid appropriation and I am participating in it, as well, with these new pieces but the difference is the message and how you talk about your work; that can’t be duplicated.”

As I sat in my New York City apartment, my last question was what Maharaj wants her art to evoke in viewers.

“I wish [for] the viewer to learn something or at least be open to learning about a history that has affected millions of people and has caused generational trauma. I want the viewer to see beyond their eyes and trust themselves to know that the beauty that is so profound in the work is also very complex. I want them to be curious and go out on their own to find out more and to really learn to appreciate brown skin on white walls.”

Maharaj is one of few Indo-Caribbean women in a field traditionally unexplored by the Indo-Caribbean community. Her work has been featured in a collection at The Art Institute of Chicago. To learn more about her work, visit www.renluka.com.