Mental health, well being, self-care, all of these terms have become even more socially acceptable so to speak out about over the past two years. Last month, Time To Talk day sparked a wave of conversations both online and offline about mental illness.

Over the past year, I have read countless discussions across social media platforms exploring how ideas about race, religion gender and sexuality are impacting our mental health in the South Asian community. Often these discussions have shown that there are clear structural issues within our communities and led many members of the ‘woke’ South Asian community to promote ideas of wellbeing, self-care and mindfulness practices. How then, can we put these ideas into practice? One such organisation whose mission it is to explore the intersection between faith, identity, masculinity effects our mental health is the award-winning non-profit The Delicate Mind.

At each of our workshops, we have representatives from the Muslim, Jewish, Christian, Sikh and Hindu communities to talk to young people about mental health and faith. To date we have worked with The Centre for Islam and Medicine, The Recovery College Tower Hamlets, Healthy London Partnership, Inspire, Citizens U.K., U.K. Youth, The Inclusive Mosque Initiative, Three Faiths Forum, to name but a few. So why the focus on faith institutions?

The ontology that ill mental health is merely a product of some chemical imbalance denies ethnic minority communities to challenge how media misrepresentation of our surroundings has contributed to the crisis we’re currently facing. For instance, the representation of the terrorist threats has led to the government robustly using the Prevent Act to tackle radicalisation in places of worship. How does this help build trust and community cohesion? How can we expect faith leaders and local government to work effectively to tackle social issues such as mental illness if we promote us versus them narrative?

[Read Related: What Stops South Asians From Discussing Mental Health?]

Whilst in many respects radicalisation of any kind should indeed be tackled as effectively as possible, this label of the ‘terrorist’ or jihadi has in many ways generated an insular defensive reaction within the community. as opposed to productive and constructive discussions to take place — a move that is now shifting.

We need to change the way we perceive social constructs such as gender and the idea of the faith leader. We recently examined this as part of our work with the Inter-faith foundation for the United Kingdom. Taking small steps to meet with faith leaders on a one-to-one basis to see how we could cooperate to tackle the issue of how mental health is dealt with within our communities is key if we’re to truly help the people care about.

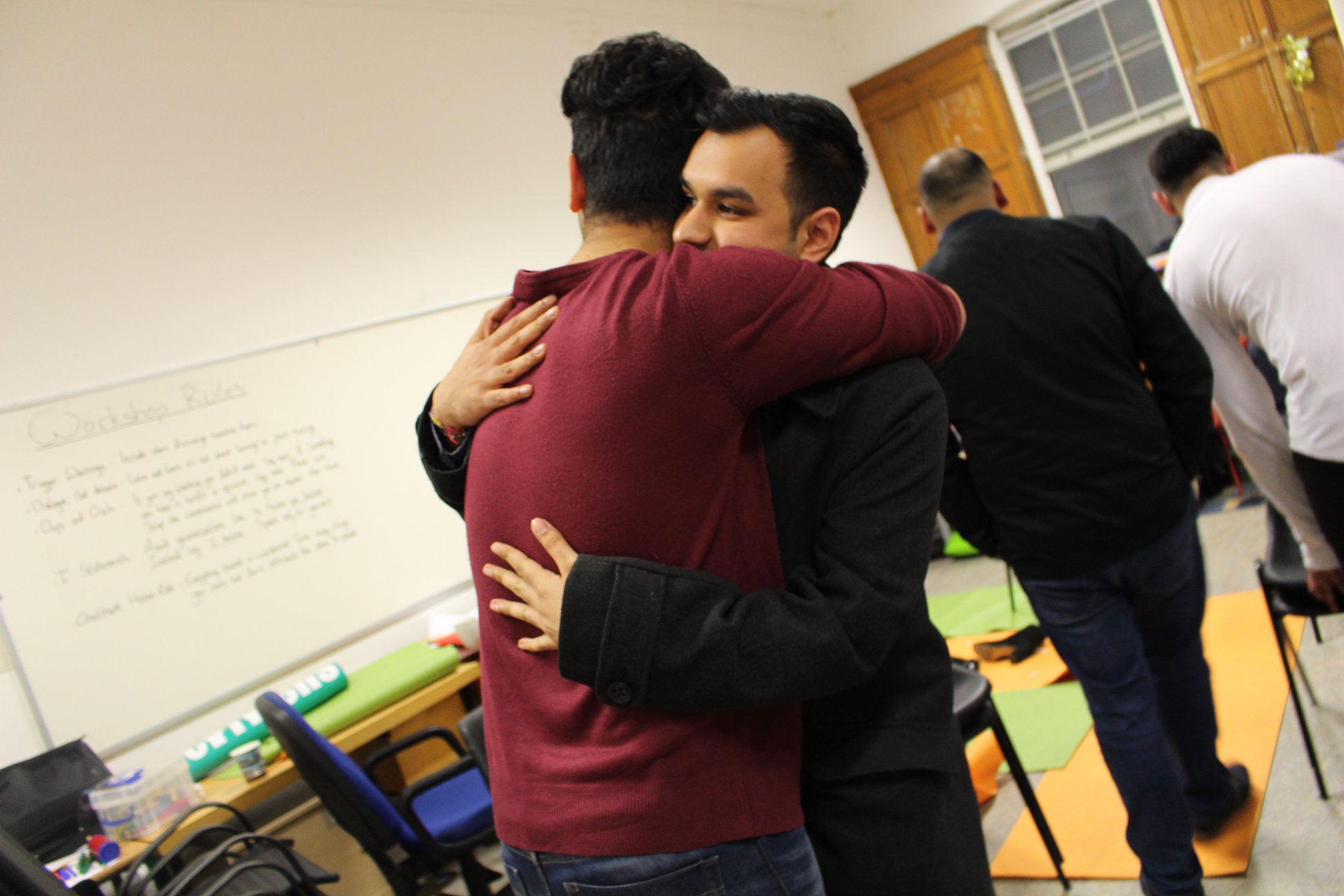

In order to build inter-generational dialogue, we ensure that participants at our workshops are able to communicate with facilitators in at least one South Asian language. Such an approach is designed to develop good communication between faith leaders, teachers, young people and parents on the topic of mental illness. Through Citizens U.K., we provide leadership training courses to re-engage them in local community projects and politics.

[Read Related: ‘RISE UP’: The Story of 4 Individuals Living with Mental Illness in India]

There is value in working together with a range of individuals who are open and willing to develop new mechanisms to tackle this prominent social issue. There is no easy route to helping those in need, building bridges takes time — we should embrace the longevity of this task. Attitudes take time to evolve, we must be willing to break from tradition to offer constructive solutions. A cohesive, intersectional approach to tackling mental illness within the South Asian community serves as a bridge to bring together key stakeholders to tackle this prevalent social issue.