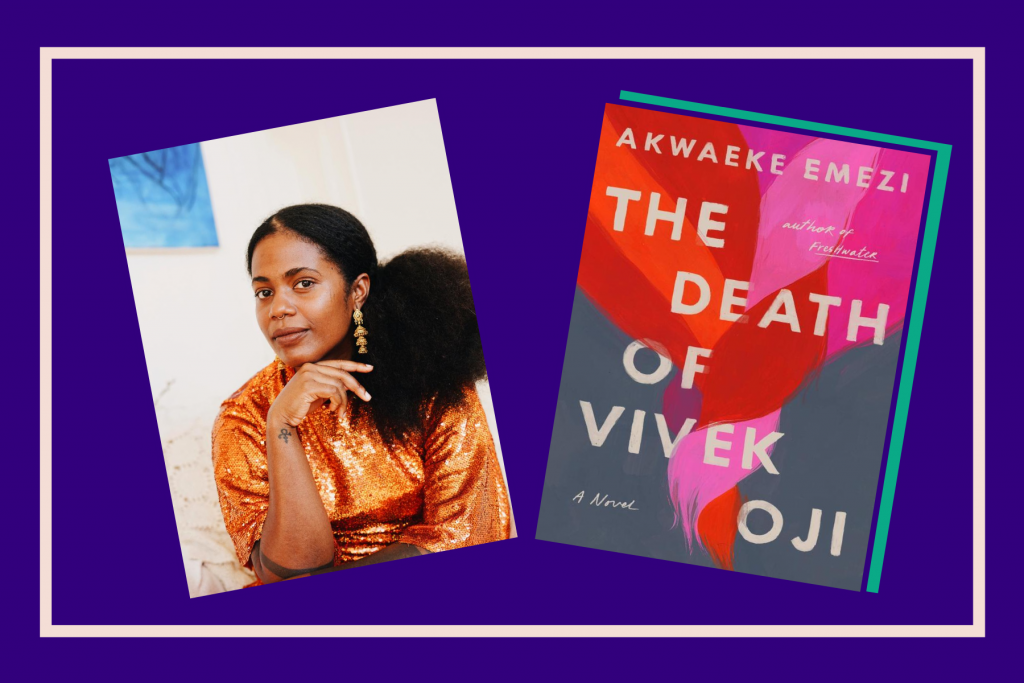

Between South Asia and West Africa, there’s ocean, there’s land, there’s air. There’s also author Akwaeke Emezi (they/them). With one lineage hailing from Sri Lanka and their other hailing from Nigeria, Emezi’s writing is both a bridge and a vehicle. Their novel, “The Death of Vivek Oji,” explores what happens when Black and brown identities intersect with repressed love.

In the first ten pages, you’ll read the words bhai, beta and murukku which are words likely familiar to BGM readers (although I call murukku “chakli”). You’ll also read the words udara, wahala, garri, and Biko which come from Igbo and Pidgin. (For reference, udara is a fruit, wahala refers to trouble, garri is a food, and Biko means please).

As you continue reading, you’ll learn how Chika, a man from southeastern Nigeria, falls in love with Kavita, a lady who moved to Nigeria to escape casteism in India. Both Chika and Kavita are looking for a fresh start, which draws them together. Their togetherness results in love, marriage and the co-creation of a queer child whom they are fundamentally unprepared to care for and fully love.

Chika responds by discontentedly disengaging and getting involved in an affair while Kavita consumes herself with endless worry and fixates on providing generous amounts of controlled and conditional love to their child, Vivek. Emezi’s portrayal of Kavita’s voice is spot-on.

[Read Related: Book Review: ‘Beyond the Gender Binary’ by Alok Vaid-Menon]

Kavita embodies what I have experienced desi moms do: loving her queer child insofar as they are not overtly queer. In other words, while Kavita believes she loves Vivek—and undoubtedly provides a better version of parental love than Chika—she fails to love bravely, wholesomely. Her love is rooted in helping rather than accepting, conforming rather than radicalizing. She serves as a liaison between a child deserving of acceptance in an unaccepting world.

This leads to secrets – secrets lead to heat, heat leads to rage, rage leads to sadness. Yet there are moments of happiness, and these moments are all thanks to Vivek’s character who is extremely likable and charming.

The most authentic depictions of ecstasy are Vivek’s sensual experiences, which Vivek’s parents never come to know. And the most authentic depictions of sheer joy arise when Vivek wears dresses and makeup—moments captured in photographs that Vivek’s parents do not see until after Vivek dies.

Photographs play an integral role in the storyline of “The Death of Vivek Oji” because Emezi critiques the assumed existence of true memory and objective truth. The novel tinkers with time to dispel singular notions of memory and truth, thus inviting pluralities, subjectivities and complex messiness.

Kavita is shocked when she sees photographs of her late-son dressed as a daughter. Having never fully known this side of Vivek, what vessel stores a memory that Kavita never had in the first place?

Her mind fails her. Vivek’s body fails her. And objects, such as the photographs, fail her.

In other words, Emezi illustrates that memory is categorically imperfect. Thus, this novel explores the value in searching for what could-be versus what-could-have-been. Emezi creates a world with infinite possibilities—limited by characters who think finitely and act even more finitely.

Emezi creates a world not so different from our own. Vivek feels restrained by the limiting factor every other narrow-minded character comprises. Emezi details this plot by oscillating the points of view chapter-by-chapter. In addition to Vivek’s chapters and the omniscient ones, we also learn from Osita’s chapters.

Osita is Vivek’s cousin-brother who ends up falling in love with Vivek, which they keep a secret. This narrative made me realize how many thoughts go unspoken in non-normative interactions where neither person feels free to express what’s on their mind.

[Read Related: Author Interview: ‘Kings, Queens, and In-Betweens’ With Tanya Boteju]

Emezi’s word-full (and wonderful) novel is a critique of this silence.

We know the climax of the story from the novel’s title alone. Vivek dies, obviously. This novel is less about figuring out the storyline and more about working backward to figure out how the storyline could have unraveled differently. Ultimately, did Vivek need to die to be accepted? Did Chika and Kavita need to suffer their child’s death to learn this lesson?

Death is something life guarantees. Both life and death distort time in different ways. The former gives the gift of time and the latter freezes time in place. Vivek was born the day Chika’s mother died, so the notion that this feminine-grandmother energy was reincarnated in Vivek scares Vivek’s family. Vivek is born into fear.

What we learn is this: Widespread shame plagues our peoples. Can queers of color experience joy? Yes. But our joy is oftentimes experienced ephemerally and in private.

You can purchase ‘The Death of Vivek Oji’ from Penguin Random House. Keep up with Akwaeke Emezi’ work on Twitter and Instagram!