While her family celebrated traditional festivities, an early-teen Sarvani Kolachana sat isolated in a room with her used sanitary napkins. Her trash, her meals and her body were to remain separate for that day.

Kolachana’s mom explained that practices deeming menstruating women impure originated because the burden on women was high. Forcing them into a separate room, at least for a week, gave them space and a moment to relax. According to Kolachana, it gave a rationale for why the rituals came into being, but in today’s times the rationale is a problematic interpretation.

“They teach you basically to be uncomfortable with your body like that,” she said. “That discomfort is taught.”

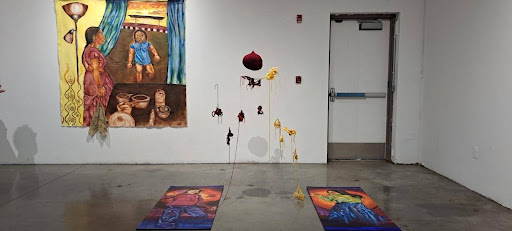

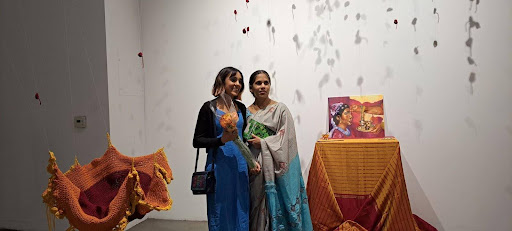

Using art as a medium, Kolachana is trying to communicate the childhood stories her mom told her, and the way she sees her mother as an adult, while reflecting on her childhood in a complex array of emotions. People around her taught her to not question the way things were and she felt ashamed when she did. Sick and disgusted but unable to do anything, Kolachana saw what tradition did to her family.

“They were so indoctrinated into this horrible belief system,” she said.

Kolachana confronted how ingrained the patriarchal and misogynistic attitudes were in her extended family while she was an undergraduate at the University of California San Diego. She actively evaluated their beliefs to find a way to have complicated discussions and change longstanding beliefs. The women in her family inspire her to think about what womanhood means in India; she thinks of her paintings as memories and seeks answers about herself.

“My identity is a queer South Asian figure and a woman. How do I think about those things?” Kolachana questions.

Kolachana doesn’t look at what she is making while her fingers deftly loop and interlock to crochet a thread from a deep red spool, a color she considers potent and related to religion. It reminds her of vermilion, bindis—womanhood, religion and energy— and menstruation.

The community of artists from the South Asian diaspora faces several dilemmas, according to the Asian Diasporic Visual Cultures and the Americas, a peer-reviewed journal. One is that livelihood, opportunities and rewards are offered to those who are “easily categorizable or serve systems that marginalize and criminalize our perspectives, while artists and culture workers who seek to subvert and ultimately dismantle these failing systems lack organized alternatives.”

Discrimination has kept their long history in the Americas a secret, forcing South Asians to disappear for safety, the study says. Now, artists in the United States are challenging the narrative of South Asian model minorities.

[Read Related: Reconciling Cultural Dilution With the Inevitable Evolution of my Diasporic Identity]

“We have a kind of a subversive strategy of South Asian American artists, particularly those who identify as queer, which is this kind of selective, revealing and obscuring,” said Anuradha Vikram, contemporary art critic, curator, writer and educator.

There are two reasons for this, she said. One is to complicate the narrative so that it is not easily reconstructed into a more singular and therefore fascist narrative. The other, she said, is when the community speaks on their issues, they’re threatening the status quo because the issues muddy the clean distinctions between black and white and brown.

“In the Bhagavad Gita, Krishna reveals his full godly power to Arjuna on the battlefield. Arjuna cannot look directly at Krishna. It is too overwhelming. He has to look away,” Vikram said, referencing the revered Hindu text. “We cannot reveal our full divinity. It is too overwhelming. People have to look away.”

The female body

For Vrinda Aggarwal, her art looks like her anxiety.

In one of her installations, ashes, menstrual blood and markings smeared onto film cast shadows on alcohol bottles filled with hair. She holds a strange relationship with her hair, she said and collecting it helps her process its loss.

The markings were obsessive and arbitrary to help her make sense of her exploration and creation while dealing with her anxiety. So were the shreds of black and white trash bags hanging over her head in her studio.

Hoping to move away from the binary of success and failure, Aggarwal works to create frameworks for herself. For example, currently, she’s working with found material. She feels collecting her hair and her blood helps her to convince herself of her existence and explore the idea of failure.

“I can’t really go wrong with collecting my hair,” she said. “I can just collect less or more of it.”

At Aggarwal’s MFA thesis exhibition, a large white wall displayed a projection of her eyes, lips and fingers in spinning spheres that were blending, vanishing and reappearing.

Beside that, hidden behind a curtain was a chair, a trash bag and an iPad playing a video with Aggarwal emerging out of the bag. She wanted to allow the visitors to experience being stuck and ripping out of it to accept themselves.

“Alcohol bottles with hair, my body discombobulated on display, it’s very bodily,” Aggarwal said when the absence of her parents was noted.

Growing up in India, Aggarwal believed that her life would be better abroad. At home, she felt she couldn’t wear certain things or be a certain way. Here, she feels women have more agency.

Anoushka Mirchandani, an Indian-born, San Francisco-based artist, had similar experiences. As a young girl in India, everyone taught her to fear her body and sexuality. Growing up, she was always looking over her shoulder.

“And the questions that always came to mind were: am I showing too much skin? Is my skirt too short? Am I inviting unwanted attention?” she said. Such questions, when they’re a part of life early on, create a dysfunctional relationship of fear and shame with one’s body.

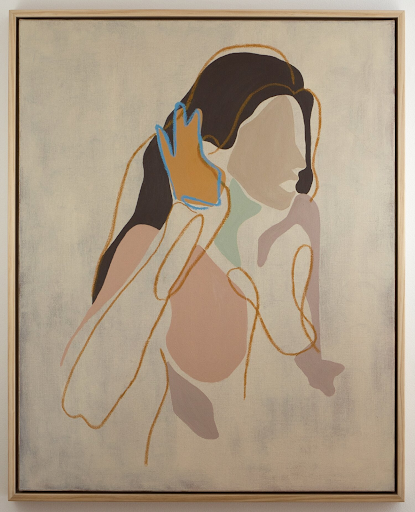

She started focusing on her art when she was trying to find her way back to herself and in many ways, it was a rediscovery of her real identity.

In her early works, she did a lot of nude figurative work: self-portraits or paintings of women around her. For Mirchandani, it was a form of therapy to find a way back to her body and mend the relationship she had with it.

“My art is a protest in terms of my own identity,” she said. “It’s just in a different, softer way.”

As a woman in America, she found the agency in her body that she never felt access to in India, and still doesn’t.

“There’s one [painting] I recently had, of me on the sofa. I’m just hanging out in my undies, on the sofa with my cat,” Mirchandani said. “There’s no way that I could carry myself like that in my personal space, in my home in India.”

Immigration and identity

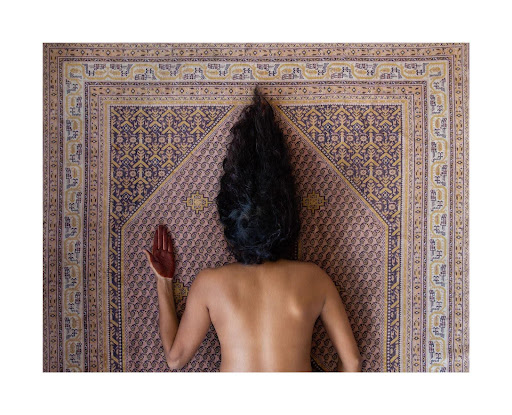

Originally from Hyderabad, India, Arshia Fatima Haq migrated to the U.S. at a very young age and frequently traveled back and forth. From early on she had a sense of being from multiple places and no place at the same time.

She didn’t intend to enter an art practice but felt the need to share things about her inner world along with the two worlds she came from as a way of locating herself and processing her identity. With her spiritual background as an Indian Muslim, she had a desire to tell those stories.

However, it was a tricky area to negotiate because of the Islamic aesthetic pedagogy and portraying the world where representation has been a contested area. One cannot make a universal generalization because, within Islam, there are many Islams, she said, and it’s a complexity that unfortunately is too often flattened and reduced.

She was entering the idea of storytelling with the complexity towards representation, both from the sense of literally drawing or photographing something and what it means on a metaphorical level to represent an experience.

“Especially one of an identity that is more culturally fraught and also coming from a feminine body,” Haq said.

Her early impulse was to speak in code, but not to conceal anything. She wanted to describe her experiences like poetry. She’s inclined to be less direct with her storytelling. She is inspired by the French writer, Édouard Glissant, who calls opacity a choice to decide what you share and conceal, especially if you’re coming from a marginalized community and looking at self-guided invisibility as a means to power or autonomy.

“I think this is a moment where there’s a lot of focus from within the institution on stories from black and brown people,” Haq said. “There’s almost like this imperative for us to tell our stories. But somehow they become kind of commodified or harnessed for other interests.”

Haq created a photo series, Rihla, as pictorial descriptions of different stages of a spiritual journey. Not recreating the six stages of this journey entirely based on research, Haq presents her own interpretation of what those might be. There’s a bit of autobiography that comes into all her projects.

As the work is about the internal journey, the person is facing away from the camera. It’s a self-portrait with a flip on what people would expect: to see the subject.

“This also ties back to one of my favorite theories, Glissant’s opacity,” Haq said. “And then again, if you’re turning inwards, you’re turning maybe away from the gaze of others.”

Aggarwal also finds herself in a conflict between the push to create art as a representation of her identity versus her own ambitions. When Aggarwal joined the Roski School of Art and Design she was expected to represent India through her work. The school, she said, emphasizes identity in the art students create.

Presently, her work deals with a sense of loss. A large part of her art explores growing up in India and studying here. Using trash, she wants to analyze what we have, lose, throw away and bring with us to a new place. She uses repetition and patterns to collect materials as a mindfulness practice to locate herself and hopes to make space for acceptance.

When Mirchandani came to the States she felt like a fish out of water. She shape-shifted to fit into the larger context of the Ohio community where she lived at the time.

“In a way, I really lost myself,” she said. “I lost a sense of who I am.”

She had to deconstruct the Indian cultural narrative that art was not a serious career. It took her a while to pursue art professionally. When she did, it felt honest because she felt she had been living an inauthentic life for a long time.

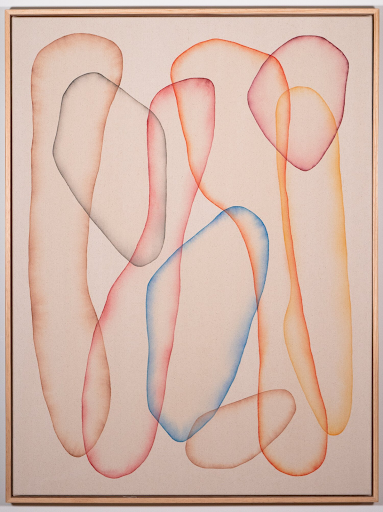

As she started to feel more present and confident in her skin, her work became less literal and figurative. While her work still carries that thread, it’s nuanced and speaks more about identity, how people carry themself in different spaces and how they feel assimilating in a foreign context.

“All of us do this. Not [just] us as immigrants,” Mirchandani said. “But we all do it in terms of when we move between different social, political, environmental contexts, we choose to reveal different parts of our identities in different contexts.”

But as an immigrant, she said, one does it more because they’re moving between vast polarities of culture. In her paintings, she fills some spaces and leaves some empty, masking and revealing the immigrant experience.

Having lived for an almost equal amount of time in both places, Mirchandani’s work does not overtly have Indian motifs. It is more soft and subtle, she said, representing how she feels about being diasporic and cobbled together in terms of identity.

“You reveal and conceal different parts in different contexts, but the paintings are the only place where all of those come together,” she said.

Collective memories and momentariness

Mirchandani’s exhibition, I Resemble Everyone But Myself, was a story of assimilation. Several paintings were based on archival photographs and interviews with her grandmothers. She placed herself into them to bring their stories into the now, mashing them together so you don’t know what’s the timeline, who’s who and what’s the generation. And it was about home; how home is not necessarily a place or a person, but a gathering of objects, places, spaces, smells, ideas, and foods.

Her grandparents never shared the stories of their migration to India during the partition. This project, Mirchandani said, brought them together to finally tell their narrative. She wants these paintings to evoke the coming together of all of their stories and journeys of assimilation. They had to assimilate into India by force. When Mirchadani had to do it in the States, she did it by choice.

“This show is for them, by me, by them,” she said.

Along similar lines of making art based on lineage, when Kolachana talks about religion, she creates things based on toxic, traditional Brahmin practices that she and her female family members have personally experienced.

Coming from a privileged and upper-caste family, Kolachana said, she doesn’t feel that she could be the right person to make commentaries on caste issues. With both her parents coming from Brahmin families, religion factored hugely into their lives contributing to her understanding herself, she said.

“I have experienced as a woman how these very deeply ritualistic traditional practices can be oppressive,” she said. She understands that women living in patriarchal spaces and cultures go unheard.

“So centering them in their labor is something that’s really important to me,” she said. “What they do to knit together families and hope [for a] patchwork society.”

One of her pieces started out as a structured recreation of a cabinet where Kolachana was trying to reconstruct a prayer room that she found as an anchor point in almost every Indian household. She hung the crocheted textile piece, suspended in space in her exhibition.

“I tried to start off with a base and build out a wall. And what I started noticing is unwillingness to conform to the rigidity of the structure of a prayer room, because crochet is such a versatile and malleable form,” Kolachana said. “So I started playing with the ways that I was crocheting. I became looser. I kind of broke out of that ritual in a way, and I created new paths for myself.”

Crochet was passed down from Kolachana’s grandma to her mom. It is an intimate thing for her mom who then taught it to Kolachana, who sees it as a through line in the lineage.

“I think of it as a feminine craft. Crochet was a means to an end for them. It was a way to occupy their time,” she said. “It’s a different kind of ritual that they would return to, to orient themselves temporally, but it’s something that they would do to beautify the role of a woman.”

Kolachana thinks of it as a metaphor for the domestic labor that’s sometimes invisible but sustains the house. By breaking the rigid form, she is inserting her voice into that tradition, which isn’t historically allowed or expected. She likes to play with the fluidity of crochet and stretch it, which she can’t do with the rituals.

“Crochet has no memory in a sense, which is really interesting because you imbue it with so much work,” she said. “And then at the end of the day, it retains none of it if you want to unravel it.”

Comparably, Haq’s ‘The Ascension’ was a project that had in its very conceptualization that ephemerality where the thing that you labor to create disappears by the time you’re done.

It was a piece representing the image of Buraq, a somewhat contested and complicated figure in its lineage. Part woman, part horse, and part wing, she had been on Haq’s mind since her childhood. Buraq probably has pre-Islamic origins and is never mentioned in the scripture. To create Buraq, Haq wanted to use gilding as a nod to religious art.

“But again, working in kind of an absurd way, to try and gild this sculpture in ice before it melts,” she said. “And then you spend all this time in labor. But then the message of it, the structure of it actually falls apart.”

When two people talk, Haq said, there’s an invisible contract that we’re agreeing to communicate about something. We somewhat reduce our own experience in order to have a shared language.

To her, the paradox in the idea of trying to represent the divine is that the divine is something that cannot be reduced. The idea of working with ice, which was going to eventually change form and lose its shape was a beautiful medium to represent that paradox. Haq has deep ties to her faith. The spiritual language, metaphors and poetry resonate with her.

[Read Related: Celebrating Femininity and Strength: The Always Raas Journey]

“Whether it’s a religious text or just a piece of literature. You can read something on a very literal level or you can read it on a more poetic level.”

To her religion is like a legal system, which sometimes works by building communities and societies by following some shared codes.

“But it is also so many times exclusionary. Our community does this and your community doesn’t. Therefore, you’re an outsider or an outcast with or without an E at the end.”

Haq believes that every person goes through a journey of discovering what the important questions are. And if you’re not thinking about it, then you’re not using the full capacity of your humanity. And sometimes rigid approaches to religion tend to take out that element of questioning.

“For me, the more interesting and profound way to approach these texts is the second way, which is to look at them almost as poetry,” Haq said. “Because it also then requires that you’re doing a more profound excavation of yourself.”