“I thought I was going to die when I was having you.”

My mother repeated this every time she shared one of the most horrific moments of her life — my birth story.

‘Didn’t all women feel similarly with their first child or first delivery?’ I would often wonder. Throughout my childhood and adolescent years, I believed my birth was the worst part of my mother’s life, starting from the first day of life.

[Read Related: Memoirs From a Psych Ward]

Before I was wheeled to the nursery to be fed, my mother probably looked over at my father and me and thought, ‘what have I done?’ She married a man who was almost 17 years older than her. She admitted she felt cornered and bullied into marrying my father by her sister and brother-in-law. The brother-in-law was my father’s cousin.

After having my first child, I realized my mother’s reaction wasn’t normal. I was an innocent baby being born, not someone trying to kill her. Childbirth was draining, emotional and raw. I was also forced to be something I detest, vulnerable. My all-women birthing team, included midwives, doula and nurses, guided me into motherhood. It was beautiful. I cried. I held my baby skin-to-skin. It was one of the best moments of my life. I felt reborn.

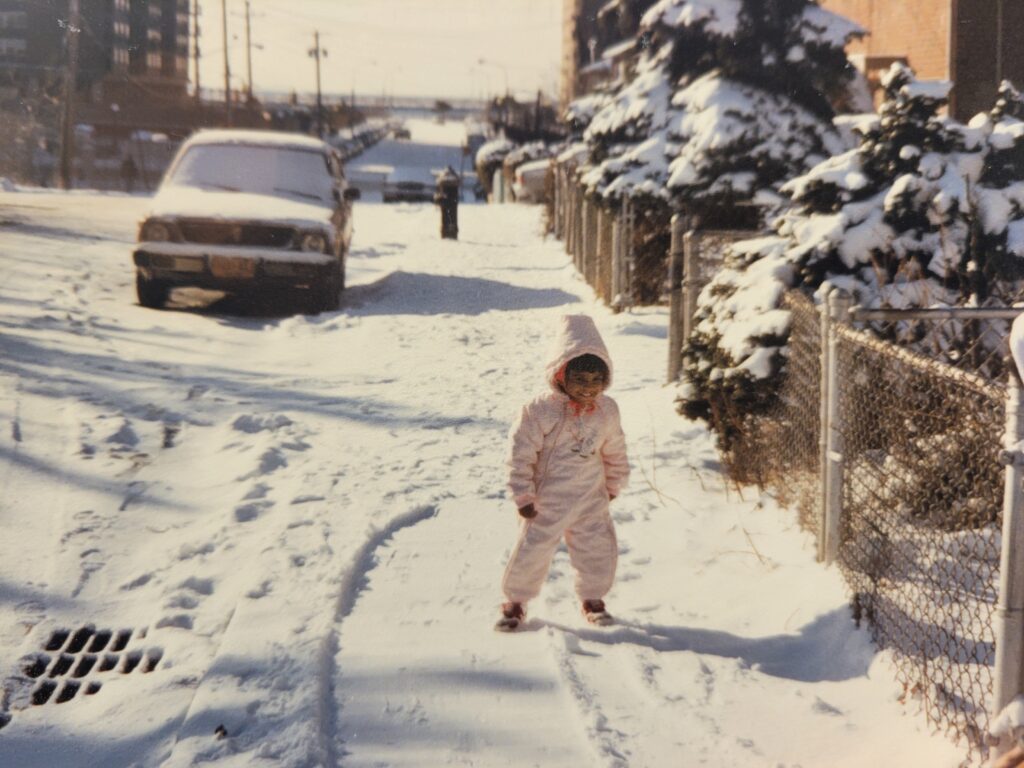

I was born “pink-pink,” a sign I would be brown-skinned like my father, unlike my fair-skinned mother. 18 months later, my mother packed necessities and wrapped me into her 23-year-old arms. She left her home with my father to start a new life. However, she underestimated my father’s wrath as she naively rekindled a relationship with her ex-husband. My father became problematic and made it his life goal to hurt my mother by using me as a pawn.

My parents were legally divorced when I was three years old, and my father was awarded primary custody. My mother had visitation rights every other weekend. Exactly how this feat was pulled off remains relatively unknown to me as an adult. More than likely, lying, bullying, and immigration, were a part of my father’s custody equation and “victory.”

View this post on Instagram

My father forbade me from calling my mother “mom.” I was forced to call his wife and my new stepmother “mom.” I did as I was told. Not long after this, at only three years old, I was directed to address my mom by her name. My father’s negative words were a constant influence.

“Your mudda (mother) left you for dead!” My father’s stone-cold words shook me.

At four years old, my childish mind translated the idea of death to flowers and bugs. But even at that age, I understood the enormity of it. My mother was a monster. My father brainwashed me to believe my mother tried to kill me.

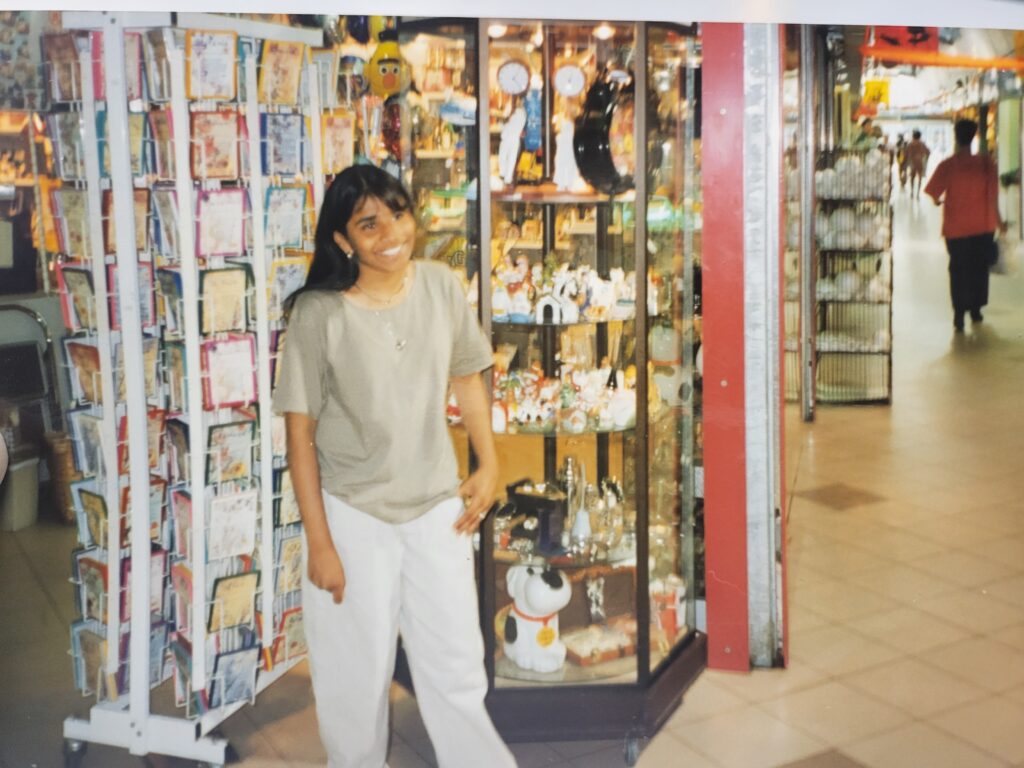

My mother named me after an Indian actress, Shabana Azmi. She liked Azmi’s natural beauty. Little did my mother know her daughter’s childhood would lack simplicity and beauty. Although she had visitation rights every other weekend, sometimes, I saw her only once a month because of my father’s ever-present vengeance to keep us apart.

In Stephanie Foo’s “What My Bones Know,” I learned about complex post-traumatic stress disorder and connected deeply to Foo’s traumatic childhood. Complex post-traumatic stress disorder (C-PTSD) is trauma over months or years, such as child abuse or trafficking. Children who live through war or chronic abuse typically have complex PTSD. In comparison, post-traumatic stress (PTSD) can occur from a single event like a car accident.

Like Foo, I took the Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) test, which is based on childhood abuse, neglect and household dysfunction. Foo and I both scored a six. I have not been professionally diagnosed with C-PTSD, though I see some parallels.

I was raised by immigrants who came to fulfill the American dream. My abusers also suffered through generational trauma. My family came as immigrants with limited resources and support. According to Foo’s research, C-PTSD and generational trauma change people’s genes and DNA. People who have suffered from C-PTSD have more health problems, such as shorter lifespans and are prone to riskier behaviors like drinking.

I have fibroids, which are also likely linked to genetics. Additionally, I have chronic back pain, which started when I was 18. Now, over 20 years later, I visit the chiropractor monthly. Trauma experts find patients have recurring issues in the lower back, stomach, intestines, heart, chest, respiratory system and several other regions. Children of trauma also go through puberty earlier. I had my first period two months after turning ten years old.

“You’re okay. Why worry about the past? These things will only upset you. Just focus on the future,” I heard from family members if I brought up my childhood trauma.

I’m unsure who is okay with denying their past. Aren’t we told we study history in school to learn from past mistakes? Yet, I was actively told to ignore my past because there was nothing to learn for my future and just the mere thought of thinking about it was a sign of weakness.

Essentially, I was being told to disassociate. Disassociation is when you are not connected to yourself and the world. But then I had my first child and started thinking about my baby and eventually my childhood. I realized I wanted to love and protect my baby the way I wasn’t — completely and unapologetically. To give my child what I wasn’t given — love, guidance, protection and more love. Through my parenting, I worked on healing my inner child.

View this post on Instagram

With Stephanie Foo’s memoir, I thought about my own healing and mental health. Foo shares that many therapists in the U.S. are white women. Up until that point, I had two therapists; both were white women I couldn’t fully connect with. I hid parts of my life, identity, faith and culture.

Today, I am actively learning coping strategies for both little and adult me. I do things I enjoy and need for my mental, social and physical well-being. “In The Body Keeps the Score,” author Bessel Van Der Kolk says, “The bodies of child abuse victims are tense and defensive until they find a way to relax and feel safe.” I started practicing yoga in my mid-20s and felt alive in my body in a way I never experienced before. My favorite pose was and still is child’s pose. On the ground, my body folded onto itself, hugging myself.

I started writing about my childhood, took writing classes and today I’m currently in two writing groups. The healing journey of abuse, trauma and neglect is ongoing. Finding a community of writers and readers has made the journey less lonely. Reading other trauma-related memoirs offered bittersweet comfort — others understood my abuse because it was a part of their history, too. I wasn’t alone.

[Read Related: Dealing With my Adoption Trauma]

Additionally, an invaluable resource I discovered was a mental health directory on Brown Gyal Diary’s directory of Indo Caribbean therapists and counselors. It lists professionals who understand the importance of cultural competency, which I and so many other Indo Caribbean women longed for.

My childhood was trauma-filled, yet my future is filled with hope. I will continue to cocoon my children in love. I will hug them three seconds longer than they desire and dedicate endless hours to story time, bedtime, playtime, mealtime and downtime. Loving them and receiving their love is ultimately the best healing tool, partnered with my writing community, therapy and supportive friends. I feel that love in my heart, soul and bones.

Featured Image Courtesy of Shutterstock