by Ravleen Kaur – Follow @browngirlmag

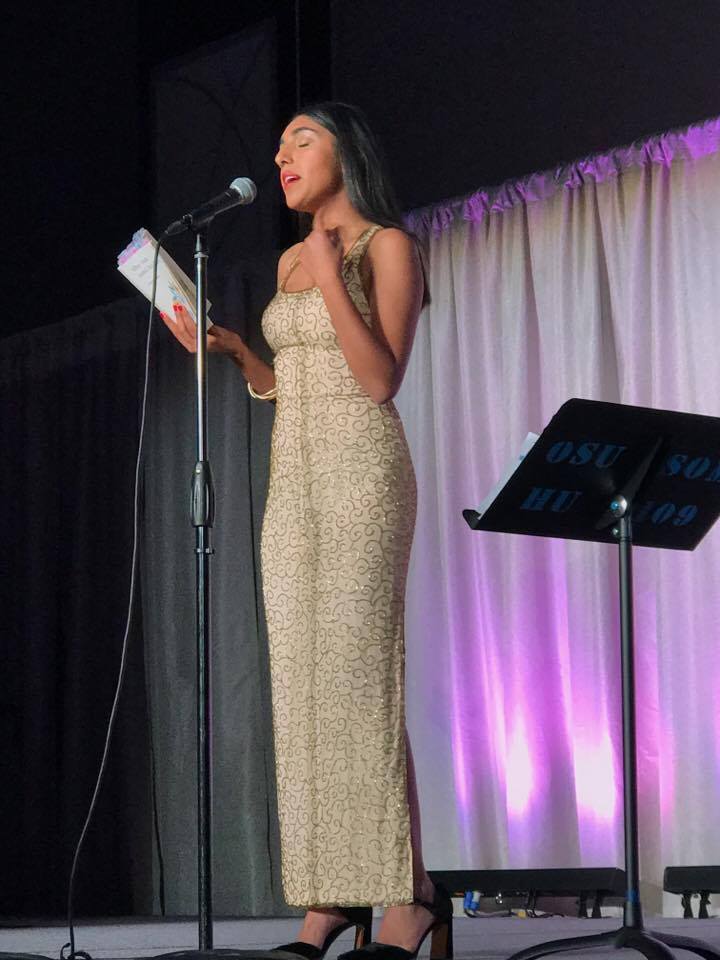

In November, The Ohio State University opened its arms to a bestselling Sikh author last. The Ohio Union Activities Board (OUAB) humanities committee organized “OUABetween the Lines with Rupi Kaur” in a ballroom full of women, clutching Kaur’s “Milk and Honey” and “The Sun and Her Flowers” close to their hearts.

I remember when I first came across Rupi Kaur a few years ago as a senior in boarding school. I spent most of my day keeping my head above the mounds of homework and readings required for classes. At this point in time, no one knew who Kaur was. I would curl up into a ball at night and scroll through her Twitter to marvel at her poems. It was my daily escape. The habit continued in college – I ordered her first book of poems and devoured it within thirty minutes.

At some point, I felt like nothing I was doing as a freshman in college really had my name written all over it. I was sick of the repetitive cycle of going to my boring classes and coming home only to shove my head into more textbooks. “Milk and Honey” inspired me to stop that cycle.

In the darkest time of my life, Kaur’s growing critical acclaim and success pointed me toward Brown Girl Magazine and a life of doing things I actually enjoy. No more pleasing others and doing what “good brown girls” are supposed to do. Kaur was the one who showed me Sikh women can succeed in writing and art. She is the reason I sent in my application to write for Brown Girl Magazine, and here I was, finally seeing her in person years later.

Kaur was striking, to say the least. She has a definitive sense of humor for someone who wrote two books about heartbreak, loss, death, and diaspora blues. For example, she started that night in November off with “Art of Living,” a spoken word about rape culture, body agency and women learning about “the consequences of the world when they should be learning math and science instead.” The spoken word was dedicated to 12-year-old Kaur. I secretly dedicated it to 12-year-old Ravleen as well.

Chapter three of “The Sun and Her Flowers” is Kaur’s favorite. Shifting focus from feminism and rape culture, this chapter delves into the immigration trauma and displacement her family experienced moving from Punjab to Canada. Kaur says she did not have the language at the time when she was writing “Milk and Honey” to document the experiences of her dad a refugee, and she an immigrant. “What was it like to make a life out of nothing?” was something Kaur constantly asked herself. She finally answered that question in her latest book of poems.

“The Sun and Her Flowers” Pg. 123 – “I still catch my mother searching for home in foreign films and the international food aisle.”

This poem addresses the process of overcoming the shame of your mother’s roots. She reminisces how she would walk farther away from her mother and act like she didn’t know her when she went into the international aisles. This unhealthy shame is something even I have learned to undo and continue to unpack with my younger brother.

The words from her next spoken word performance, “What Love Looks Like,” threw me into a fit of laughter and tears.

“I can’t believe I thought love looked like a 5’11 tall brown-skinned man who likes frozen pizza for breakfast,” she said.

I know at least five other girls who thought this too. We grow up in a culture where everyone celebrates a desi boy doing the dishes and forces girls to put everything on the line for a man. Kaur says love starts within us – everything else is a projection of our wants and fantasies.

And lastly, Kaur gave an ode to her Sikh heritage with a light-hearted poem.

“The Sun and Her Flowers” Pg. 217: You can’t keep two lovers apart.” She then points to her eyebrows and said, “These hairs grow back because they’re supposed to be there.”

Kaur later spoke about the bullying her brother, a sardar, faced growing up in Canada with unshorn hair.

For the first time in my life, I felt like literature had been written for me. Here we had Kaur in the flesh addressing our religion and bullying on a stage in front of hundreds of college students eager to listen to her every word. She had brought Sikhi, feminism, and immigration to the forefront and thrust it in young people’s faces to devour. You could gush over her poems about love but not without sifting through pages documenting the trauma women of color go through.

For the first time in my life, I felt seen.

Ravleen is a senior at The Ohio State University with a passion for politics, writing, and Punjabi virsa. When she’s not writing her own pieces, she’s busy reading the works of influential women, especially anthologies. She ultimately aspires to have a career in healthcare where she can use her skills and experience to achieve efficiency and equity in the healthcare system.

Ravleen is a senior at The Ohio State University with a passion for politics, writing, and Punjabi virsa. When she’s not writing her own pieces, she’s busy reading the works of influential women, especially anthologies. She ultimately aspires to have a career in healthcare where she can use her skills and experience to achieve efficiency and equity in the healthcare system.