As someone with “Pyar Dosti Hai” tattooed in Hindi on my wrist, you’d be hard-pressed to find anyone who wanted “Ae Dil Hai Mushkil” to live up to the hype every Karan Johar movie deserves more than I did. Unfortunately, our trusted maker of hits such as “Kuch Kuch Hota Hai” and “Kabhi Khushi Kabhi Gham” is stuck in the melodramatic 90s and early 00s—and assumes we are too.

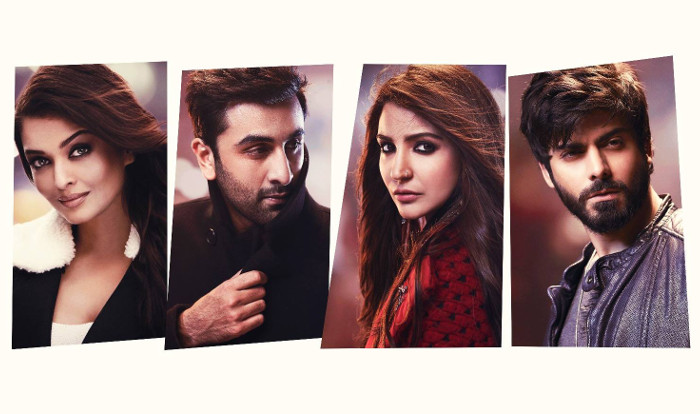

In his “return” to the big screen (when did this become a taboo thing to say, by the way?) after “Bombay Talkies” (2013), Johar brings us the story of Ayan (Ranbir Kapoor) and Alizeh (Anushka Sharma). Ayan and Alizeh meet at a club and make out—but he wants to date her and she just wants to be friends. (Read the latter half of that sentence over again a few times, and I’ve not only just spoiled the movie for you, I’ve saved you two and a half hours of agony.)

[Read Related: “Everything we Know About Karan Johar’s Upcoming Film, Ae Dil Hai Mushkil“]

They embark upon a years-long (sometimes, it felt like decades) journey in and around the topic of love and friendship. Ayan pines over her endlessly, as she fairly and justly (and repeatedly) tells him she just wants to be friends. Ayan then finds every possible way to cry, whine, throw tantrums, almost physically abuse, and actually emotional abuse to get his way. Exes (Fawad Khan) and new loves (Aishwarya Rai) be damned, Ayan wants Alizeh to love him back—and Alizeh just wants the emotional attachment of a best friend without the GREAT BURDEN of a relationship (even though she was all down to get married to her ex, Ali).

The plot loses its charm in the second half when the clear back and forth between Ayan and Alizeh starts to get a little old. Add in an unnecessary tragic twist or two, and you have a completely wasted, terribly thrown-off story of unrequited love.

Plot aside, let’s talk about performances. For starters, how many movies are we going to see Kapoor pining and whining over a girl in? Does he have this routine down pat yet? Kapoor is convincing in his portrayal of Ayan and gets a lot of sympathy too—until he literally starts throwing things and screaming at Alizeh.

Sharma as Alizeh is literally loud. She shrieks and yells, taking the embodiment of a modern, independent Indian woman a little too far like she’s trying to hit us over the head with it. As a psychologist, I wondered if Alizeh was just mad at the world for some unbeknownst reason because I could not understand why she had to yell so damn much.

Rai and Khan played side roles, which are just simply wasted. Rai, in particular, is a saving grace for ADHM in a lot of ways—she brings class, elegance and brevity to her role. It seems a little over the top for Johar to sexualize her role so much, however, which is unfortunate because she actually did a pretty good job with the emotional aspect of caring for a childish Ayan. As for Khan, well, he’s not in the movie much—which is appalling considering the amount of controversy that stemmed from nothing, really.

In terms of direction, there are certain things we expect from Johar, such as stunning outdoor locations, evergreen melodies, and slick, chic fashion on good-looking actors. On this front, the director delivers and delivers well. Here, his maturation shows. He’s grown up, shows artistic precision, and unfolds a beautiful world outside of what most of his audiences have seen in real life.

However, all the other things we expect from Johar, such as unrequited love, cheesy dialogues, complex love triangles, and over-the-top tragedy, also show up. The issue here is not that these aren’t done well—they are. But in a movie like ADHM, for as modern as it looks, these tropes become archaic. They weigh the movie down, and instead of making the audience nostalgic for old times, just make it seem like he couldn’t come up with anything new to entertain us with. (Such as playing the “Kal Ho Naa Ho” music in a certain scene, much like he played “Kuch Kuch Hota Hai” music in “Kabhi Khushi Kabhi Gham’s” “Suraj Hua Madham.”)

[Read Related: “5 Reasons We’re Excited ‘Koffee with Karan’ is Back!“]

There are those who really liked ADHM, and more power to them for such. Maybe, as a hardcore 90s Bollywood fanatic, I have outgrown my desire to see the kinds of love stories on the big screen that we once did. Johar isn’t so much at fault here—ADHM is a mashup of everything he’s ever done well as a director and producer, redundant but with a shiny new coat of paint.

I think I get it, though. I believe Johar’s message about the distinction between love and friendship itself shows how much he’s grown up since the days of equating the two (pyar dosti hai). Love is friendship? It’s not so simple, he insists. Instead, he works hard to forge a line between love and friendship, and stubbornly holds both sides away from each other long after it becomes clear that the line has been blurred.

Overall, ADHM is everything you expect from a Johar movie, with a modern spin. With great music, wonderful cinematography and a great cast, it’s worth at least one viewing. I, however, will probably soon forget to add ADHM to my Bollywood DVD collection, which, until now, included every single one of Johar’s own directorial ventures.

Priya Arora is a queer-identified community activist, writer, and Netflix enthusiast. Born and raised in California, Priya has found a home in New York City, where she currently works as a Web Editor at Hearst Business Media. When she’s not working, Priya enjoys watching old school Bollywood movies, playing Candy Crush, reading, and eating way too much of her partner’s homemade Hyderabadi biryani.

Priya Arora is a queer-identified community activist, writer, and Netflix enthusiast. Born and raised in California, Priya has found a home in New York City, where she currently works as a Web Editor at Hearst Business Media. When she’s not working, Priya enjoys watching old school Bollywood movies, playing Candy Crush, reading, and eating way too much of her partner’s homemade Hyderabadi biryani.