by Priya Arora – Follow @ThePriyaArora

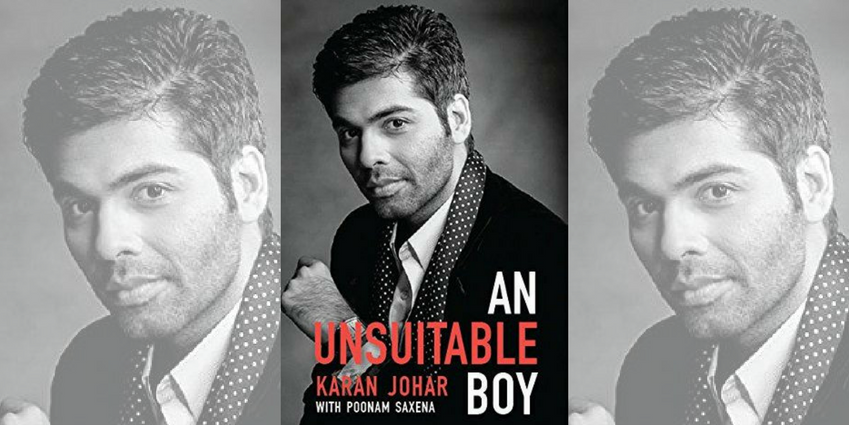

Over the weekend, The Times of India released an excerpt of acclaimed Bollywood director Karan Johar’s upcoming biography, “An Unsuitable Boy.” In it, Johar talks openly and honestly about issues he’s faced in learning to love himself, his body, and coming to terms with sex and sexuality. The piece has gotten a lot of attention, and brings up a topic many of us are tired of talking about: Johar’s sexual orientation. So, this begs the question—why are we so obsessed with Karan Johar’s outness?

Johar wonders the same thing in the excerpt of his book, co-written with Poonam Saxena, and slated to release later this month:

“While growing up, I was combating a hundred issues in my head. The thought of sex made me awkward; it almost rattled me. I thought, am I asexual? Why am I not feeling this? Why am I not doing anything? There was a lot of turbulence in my head.

Today, people think that I have all the possible avenues to have all the sex in the world. But that’s not who I am at all. To me, sex is a very, very personal and a very intimate feeling. It’s not something that I can do casually, with just about anyone. I have to invest in it.

I get scared of being spotted with any single man now because I think they are going to think that I am sleeping with him. I mean, firstly I have never ever talked about my orientation or sexuality because whether I am heterosexual, homosexual, bisexual, asexual, it is my concern. I refuse to talk about it…I have not been brought up to talk about my sex life.

Everybody knows what my sexual orientation is. I don’t need to scream it out. And if I need to spell it out, I won’t only because I live in a country where I could possibly be jailed for saying this. Which is why I Karan Johar will not say the three words that possibly everybody knows about me in any case.”

In other parts of the excerpt, Johar also talks about facing more than 200 tweets a day berating him for his sexuality, as well as the painful toll a rumor of his romantic involvement with best friend Shah Rukh Khan took.

There have been a lot of reactions to Johar’s dose of honesty, some supportive:

A brave knight in shining Louboutins slaying his dragons @karanjohar you better send me An Unsuitable Boy as soon as you are back! https://t.co/oCKGdbD131

— Twinkle Khanna (@mrsfunnybones) January 8, 2017

I’m no @karanjohar fan but this excerpt in today’s Times from his autobiography is so brave and moving, I’m surely one now. @PenguinIndia pic.twitter.com/pzrhcWpcUk

— Pritish Nandy (@PritishNandy) January 8, 2017

And others not so much, mainly from LGBTQ activists based in India:

“All the people think I am gay but I dont want to talk about it” ? OUT #CommonSense #pride #India

— Pallav Patankar (@Pallav01) January 8, 2017

Shibu Thomas, Senior Assistant Editor at The Times of India, wrote:

“By refusing to say those “three words,” you empower the abusers. You make it seem as if there is something to be ashamed of in those three words. Something that gives society the right to browbeat you, call you names, prevent you from loving the person of your choice, extort and blackmail you and shame you into the closet.”

Acclaimed author and Huffington Post India Contributing Editor Sandip Roy wrote that he, instead, felt sadness for Johar. His assertion was that Johar’s loneliness shone through his words and that Johar’s fear came from a fallacy—he could not be jailed for saying he’s gay, but for actually performing the act.

“Karan Johar owes it to no one to be a poster boy for gay rights or any rights in India. He has a perfect right to be out or not out, or semi-out. He can say his three words or not say them. It’s entirely unfair to expect him to lead the Rainbow Parade. He is not obligated to be anyone’s role model any more than the LGBT community is obligated to give him a pass on his depiction of queer characters on screen.”

I largely agree with Roy. As disappointed with “Dostana” as I was, and as much as the 14-year-old me would’ve loved a gay Indian celebrity role model, I don’t think it’s fair to expect Johar to “come out.” After all, he’s clearly gone through a lot to come out to himself, let alone those around him. It takes a certain level of growth to come from the experiences Johar describes in this book to standing on stage at the All India Bakchod roast with his mom in the front row as one comedian after another comedian took aim at Johar with every gay joke in the book.

Whenever anyone sees my hair, or the masculine clothes I wear, one of the very first questions they ask is, when did you come out? For some, its amazement and respect, and for some, it’s a little voyeuristic. They want to hear a dramatic story, or merely expect one because of the culture I so proudly carry forth from my parents.

My answer each time can vary, but the underlying truth is, coming out is constant. Coming out to oneself is an incredibly personal and moving journey in and of itself. Then there is the whole, everyone else, part of it. I come out every single day I step out with short hair and men’s clothes or get called “sir” or my partner and I get stared at on the subway as we hold hands.

Last month, Nimisha Mishra wrote a piece titled, “The Longest Coming Out Party Ever,” in which she described at length the seemingly unbearable lack of subtlety Karan Johar has shown in displaying (or alluding to) his sexuality on the latest season of “Koffee with Karan.”

The piece, and its terrible sense of mockery in the light of a gross misunderstanding of what it’s like living (and coming out) as a sexual minority, was an infuriating read. Dripping with self-righteousness and heterosexual privilege, Mishra’s words caused me to pause and remind myself that I, nor Johar, owe Mishra or anyone else an apology for living their truth.

“Nobody will arrest you if you come out, people do not get arrested for that in our country anymore,” Mishra wrote.

“It seems to me that KJo has padlocked himself and created Koffee With Karan to cut a peephole into his own sexuality. KJo has fielded these questions for years and now that they’ve stopped coming, he’s trying to get us to ask them again, so that he can go back to fielding them.

I don’t know about you, but this season has felt like the longest coming-out party to me, hosted by a man caught up in an eternal toss-up between wanting desperately to come out and dreading our judgment at the same time.”

The “just come out” trope is the highest form of heterosexual privilege. Do you have to stop acting so straight in your daily life to make those around suddenly so much more comfortable? Are you ever asked to describe details of your sex life because someone just doesn’t get “how you do it”?

For me, Johar’s story is a reminder that outness is a privilege and one that, whether I’m marching in a Pride Parade or not, I have the ability to use that outness to enact change—if and when I so choose. Johar has the same choice.

I still remember the power I felt marching with SALGA a couple of years ago in India’s Independence Day Parade in Manhattan, handing out multiple language flyers to desi aunties and uncles who tried to make sense of our rainbow flags—or outright ignored it. I imagine the little kid, like me so long ago, standing on the sidewalks with his parents. He feels different, weird, alone… and he doesn’t know why. He sees a rainbow flag. He sees brown people who are as desi as they are gay… happy, really. That’s who I marched for.

Do I wish Johar could march in a pride parade? Absolutely. Do I wish Johar could embrace the LGBTQ community in India and have found the support he might’ve needed along the way all these years—and at some point give back the support that so many others still need? Definitely.

But that has been, and always be, his choice.

Roy also wrote in his article:

“The LGBT community already has its leaders, the ones who march in parades, the ones who challenged Section 377 in courts over the years, the ones who go on television talk shows, the same-sex couples who are raising their children and taking them to school every day just like everyone else. That community would welcome a Karan Johar but no one is waiting for him either.

What is truly sad for Karan Johar is that in so many ways, his country has moved on. Those born to far less privilege have figured out ways to be far more comfortable in their own skins.”

I don’t doubt that Johar has the privilege of supportive chosen family and is proud of who he is and what he’s accomplished.

I’m proud of Karan Johar, too. He’s grown up, and in his truth—the one that smashes a closet and demands that he is known on the basis of his blockbuster films not who he sleeps with—I find incredible inspiration.

Priya Arora is a queer-identified community activist, editor, writer, and Netflix enthusiast. Born and raised in California, Priya has found a home in New York City, where she currently works as a Web Editor at Hearst Business Media. When she’s not working, Priya enjoys watching old school Bollywood movies, obsessively playing Candy Crush, reading books she never finishes, and eating way too much of her partner’s homemade Hyderabadi biryani.

Priya Arora is a queer-identified community activist, editor, writer, and Netflix enthusiast. Born and raised in California, Priya has found a home in New York City, where she currently works as a Web Editor at Hearst Business Media. When she’s not working, Priya enjoys watching old school Bollywood movies, obsessively playing Candy Crush, reading books she never finishes, and eating way too much of her partner’s homemade Hyderabadi biryani.