Content warning: domestic violence, abuse, self-harm

Ask a woman about her hair, and she might just tell you the story of her life. – Elizabeth Benedict

Growing up, I practiced Sikhism—a 500-year-old religion rooted in the beliefs of selfless service, that there is one God, men and women are equal and keeping uncut hair is a sign of respect to the Creator. My father was, and is a devout Sikh; so, we grew out our hair, prayed every morning and went to the gurudwara every day. I went to Sunday school for eight years and taught there for three. We had a room at home devoted to praying. We seemed like your typical Sikh Punjabi family, more or less.

Except we weren’t.

Because learning Sikhi at the gurudwara was different than learning Sikhi at home. Because when my father beat my mom for 19 years, it didn’t seem like he believed in equality. When he kept us from seeing the rest of our family, it didn’t seem like he believed in kindness. When he verbally abused and degraded me, it didn’t seem like he wanted me to grow as a person, but rather just to grow my hair as a physical symbol of my devotion to God. Living life as a walking display of his hypocrisy deepened the disconnect between who I was and who I wanted to be.

***

The year is 2014, in the month of February. I wake up at around one or two in the morning and hear my mother screaming. Carefully, I tiptoe out of bed and to my door. I hear her sobbing loudly. She’s shouting at my father. Telling him to stop. Cautiously I whisper, “Mama,” barely loud enough for her to hear. She’s still crying. “Mama,” I breathe. I hear her struggling. I peer my head out of the doorway and see that their bedroom doors are closed. I know they’re locked. “Mama!” I call again. I’m shaking now, just pleading with my eyes for my dad to come and open the doors so she can get away.

“Go to bed.” I turn and see my father coming out of the prayer room. I’m glued to the floor. My body is quivering. He yells at me to go back to bed. I shuffle back to my room, tears dripping down my face, unable to comprehend what was happening. I’m dreaming. I lie down in bed and hear her cries once again. And while she screams, I writhe in pain with her until I fall back asleep.

***

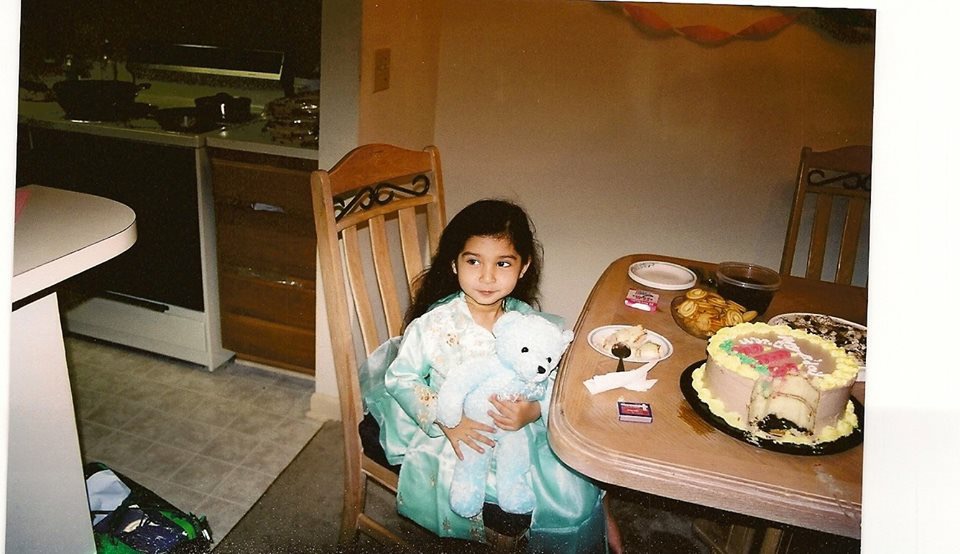

The first time I noticed that my father was abusive was when I was about four years old. I had just finished getting ready for school that morning, wearing one of the many Costco frocks laid out for me. I sat in my parent’s bedroom, ready to watch my morning dose of “Caillou” when I heard shouting—my father yelling at my mother. Then I heard a thud. I don’t know how I knew, but immediately, I pictured my dad pushing my mom down the stairs. I remember being too scared to get up and check.

A few weeks later, he went on a business trip to Ohio. When I got ready for school that Monday, my mom laughed and said that my dad had accidentally taken her car keys with him. So I didn’t go to school that week. I didn’t think much of it until the day my dad was going to come back. My mom and I went on a walk in a nearby park and I noticed she had tears in her eyes. “What’s wrong, Mama?” She burst into tears.

When I was in fourth grade, we were having a party at my house for my grandfather on the weekend leading up to my mother’s birthday. I was in my parent’s master bathroom where my mom was braiding my hair and my dad was tying his turban. I don’t know why he was mad, but he was yelling at her. She kept combing through my tangles, separating the hair into two guths. He kicked her from behind into the open drawer next to where I was standing.

Later that week, I told my teacher what was going on at home. I sat there, shaking, trying to put together the words. I knew what was going on at home wasn’t okay, but what was I supposed to say? Child Protective Services consequently got involved and went to my home to investigate. They interviewed my parents, but of course, my father was charming and charismatic and said there was nothing to worry about. I remember the day they came to interview me and my sister. My dad was volunteering with my “Girls on the Run” team and on the way back home, he yelled at me for telling anyone about what was going on at home. It was supposed to stay in the family. Did I want to be taken away from my parents? Keep quiet. I can still recall the fear coursing through my veins when I saw my dad standing outside the office door while CPS interviewed me.

In seventh grade, I started self-harming. I began to question the worth of my existence. I felt like I was the reason my father beat my mom, the reason she was living the hell that she was. When my dad read the texts I had sent a friend about being suicidal, I was punished. How could I have shared such personal details with someone my parents didn’t even know? Why was I being so dramatic?

A year later, my mom was able to move out for a month. She tried filing for a divorce but ultimately, my father convinced her he’d change, and she came back home. During that month, he complained to me about how his in-laws (my mother’s parents) hadn’t reached out to him, how they hadn’t convinced my mom to stay. I remember finding some ounce of courage to ask what he’d do if when I was older I told him my husband was doing the things he did to my mom.

I’d tell you to make it work.

I wish I could write about how to deal with an abusive father. I wish I could tell you how to get out and never look back. But the truth is, I’m still figuring it out. During my sophomore year, fed up with dichotomy, I moved out of my father’s house. It took a lot of time and build up, and was only really possible because my mother had paved the way and was willing to support me. But leaving didn’t seem like enough; I still felt anchored to the ambidextrous life I was raised in. About a month after moving out, I did what my father had taught me was the most abhorrent sin I could commit: I cut my hair.

At first, I felt sick and guilty. I grew up as a confident girl who was always second-guessing herself. I grew up as an outspoken girl who never learned how to use her voice. I grew up as an independent girl who craved the approval of her parents and community. I was a walking contradiction with no direction. Cutting my hair made me choose. I was put in a position where I either stood up for my mother and myself, or accepted this life.

As time progressed, I felt empowered. It was the first decision I had made on my own, the first act of formal defiance that changed me as a person. Because not only was I cutting my sacred hair, I was cutting the ties with my father. I was cutting away the notion that the length of my hair defined my character. I was cutting myself off from the abusive, controlling, depreciative man who called himself my father. I was supporting my mother, condemning his actions, and creating a path for myself to grow. To my father, it looked like betrayal, but there are two sides to every coin.

Religion and family offer solace to people in times of need. They serve as a vehicle to mature and grow. For me, it was the opposite. My interpretation of religion had been warped. On the one hand, there was a beautiful religion steeped in sharing and giving and caring. On the other was a community who praised my father’s devotion, while he used Sikhism to justify evil behind closed doors.

I am still learning how to navigate my own perceptions of the man who raised me. I don’t know if I’ll ever be able to forgive him. But at the end of the day, I now know who I am outside of his control. I am a strong woman of color who can use her voice to spread awareness about issues she cares about. I am a bhangra dancer who is able to appreciate my culture despite the difficulties I experienced within it growing up.

Ask a woman about her hair and she’ll tell you her entire life story.

My name is Saniya. I’m 20 years old. My hair is black, hangs just above my shoulders, and looks great curled. It’s a piece of me, but I’ve learned that it doesn’t define me.