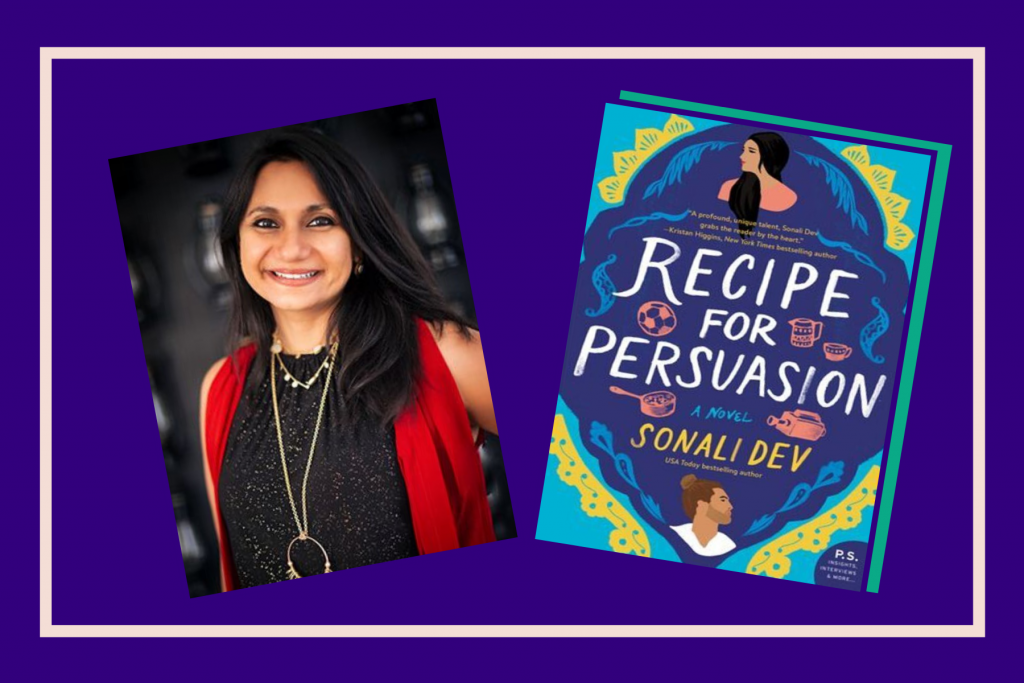

Chicago-based author Sonali Dev’s new book, “Recipe for Persuasion,” is the second in The Rajes series after “Pride, Prejudice and Other Flavors.” “Recipe for Persuasion” follows thirty-year-old Chef Ashna Raje, who is tasked with saving her dad’s fledgling restaurant, Curried Dreams. When she is asked to join the cast of Cooking with the Stars, a hit reality show that pairs chefs with celebrities, Ashna is paired with Rico Silva, her first love. Their reconnection confronts Ashna with past trauma and rekindled feelings in this loose retelling of Jane Austen’s novel, “Persuasion.”

Read Related: [Fulfill your Desi Cravings With this ‘Indian-ish’ Recipe Book]

“Recipe for Persuasion” and “Pride, Prejudice and Other Flavors” are the first two installments in Dev’s four-part series. These stand-alone novels released in May 2020 and May 2019 respectively.

Dev uses themes and lessons from her four favorite Austen novels—“Pride and Prejudice,” “Sense and Sensibility,” “Persuasion” and “Emma”—to tell the story of the Rajes family, an ambitious Indian-American family based in the Bay Area whose oldest son is running for California governor. Inspired by Austen’s works at a young age, Dev made it her goal to write this four-part series as a homage to what the novels have taught her.

View this post on Instagram

Ever since I was a little girl, and ever since I read Austen and got obsessed with her books, I always imagined that I will write books inspired by them or write retellings of them. As I grew up, especially after I became a writer and I had written a few novels, I realized that I didn’t want to just take her stories scene by scene and transfer them into a different culture. That has been done over and over again. What I wanted to do was take what I had learned from her stories, and take the personal impact that she had had on me and translate that into stories.

Dev was raised in Mumbai, India, and her first exposure to Austen’s novels was in the seventh grade from Indian TV series “Trishna,” an Indian adaptation of “Pride and Prejudice.” Dev was fascinated by a character named Rekha who parallels Lizzie Bennet’s character.

[Rekha] was a girl who was incredibly opinionated, who didn’t pander at all to what was expected of her in terms of being ladylike. Those things lined up with what I naturally believed, even at that age. Suddenly there was a heroine who I was like ‘Wow, she’s loved because of her opinions,’ ‘She’s liked because she’s contrary.’ That, to me, was so freeing.

After checking out Pride and Prejudice from her school library, Dev read the book over and over again throughout her life. What stood out to her about Austen’s work was the female focus and palpable humanity of her characters, aspects she carried into her own writing.

We were reading a lot of British literature because this was English education in India, and rarely was the focus ever on a female protagonist. It was so rare to find an author who, 200 years ago now, not only had female characters on the page, who dared to desire things, but they actually got them. They made huge errors in judgment, in behavior, and they still found happiness. This whole idea, that we can want things and we can desire things and that there’s not only one chance to get things right was something that I initially learned from her work. Recipe for Persuasion specifically is my homage to what I learned from Persuasion, which was that you can make mistakes, and there will always be a second chance.

In “Recipe for Persuasion,” Ashna also reconnects with her estranged mother, Shoban, or Shobi. Their interaction highlights Ashna’s traumatic childhood, and the emotional wounds she has to work through to move on from it.

Each child can tell the difference between their parents bickering and their parents actually wounding each other with words. Children are able to tell the difference, and a lot of us just assume they aren’t. And then each child finds their way around it, whether they’re going to bury it, or whether they’re going to block it out, or if it’s going to devastate them, and that’s each person’s personality. Ashna happens to be a child who internalizes it as her own feelings, as not being good enough, as abandonment, and it’s very overt in her life. She internalizes it to a point where she gives up things that would make her happy. There is a very specific journey for her to go back, find out where that wound happened and pick herself up off the floor and accept that it was not her fault.

For Dev, exploring the perspective of Shoban, a woman who made the choice to put her own needs before that of her family’s, felt important. Her South Asian upbringing, including Bollywood movies like “Kabhi Kabhi” and “Hum Dil De Chuke Sanam,” emphasized that compromise is crucial to happiness for women, a narrative that Dev wanted to flip in her own storytelling.

View this post on Instagram

Shoban to me is a character who is my scream against the patriarchy. The more I got to know her, I started to realize that all the things growing up that had bothered me about the world, that were overtly patriarchal. I wanted to explore a woman who says, ‘No. My desires matter, and I am going to put my desires before what everybody else thinks I should be doing and I’m going to live my life on my own terms.’ Of course, there’s collateral damage, and Ashna is that collateral damage. But I wanted a woman who had made that decision, who had lost [family and motherhood], and then made a journey back to finding that, but without compromising what she wanted in her life.

While her work has a “Bollywood beat” inspired by her culture, upbringing, and experiences, Dev tries to focus on the humanity of her characters in her books.

My books follow Indian characters, thus far, but they’re not only Indian. I want to focus the stories on stories, rather than just culture – switching the narrative to focus on parts of the community that are open-minded, that aren’t as inward-looking. Anything we do in this country in terms of the arts we were taught to rely on praising the white gaze, and you’re trying to do that tightrope walk between authenticity and acceptance. I try not to do that, and tell the stories that are my truth and not make it ‘consumable.’ I want anyone that reads my books to walk away with the sense that they don’t have to be exactly like anybody else, and question whatever narratives they have internalized.

Read Related: [#BornConfused15: ‘The Power of Fiction is Giving you the Experience of Walking in Someone Else’s Shoes’]

Dev is currently writing the third book in The Rajes series inspired by “Sense & Sensibility.” The third installment will focus on Yash, the eldest son of the Rajes, who is running for California governor. The book will explore ideas such as the compromises made for political power.

*This interview has been edited for clarity.

You can purchase Recipe for Persuasion from HarperCollins. Keep up with Sonali Dev’s work on Twitter!