by Natasha Sharma – Follow @BrownGirlMag

As I walked out of the theater after watching Kumail Nanjiani’s “The Big Sick,” a myriad of thoughts ran through my head. Let me begin by stating that I feel that there are positive aspects of this film, and it is what I would consider a step in the right direction. This is the first Hollywood romantic comedy in which a South Asian plays a lead role.

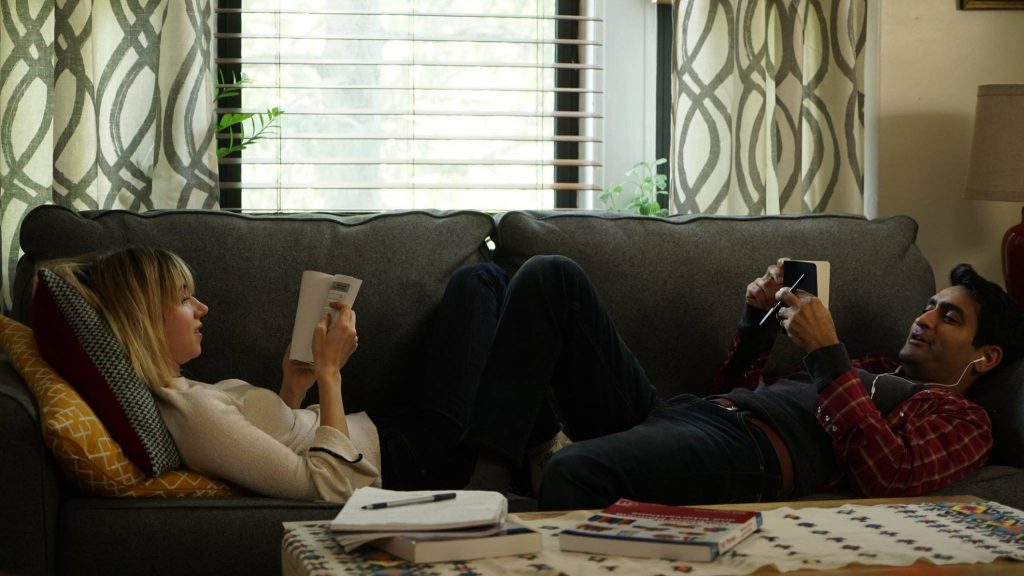

Nanjiani and actress Zoe Kazan portray Nanjiani’s relationship with his real-life spouse, Emily Gordon. As a brown woman, it was undoubtedly exciting to see someone of my ethnic background acting in a mainstream film. Considering that South Asians have an extremely limited presence in the western media, and are more often than not relegated to peripheral, stereotypical roles, it was refreshing to watch a brown person depicted as a regular person.

That being said, there are several challenges associated with this film, particularly when it comes to its portrayal of South Asian women, families, and culture. “The Big Sick” served as a reminder that, despite South Asians’ increased visibility over the years, western media still has a long way to go when it comes to its representation of racial minorities.

First and foremost, I was bothered by Nanjiani’s presentation of South Asian women as caricatures who are boring, predictable, and submissive. While Emily was portrayed as an attractive, spontaneous, witty, and independent individual, the South Asian women who were potential rishtas (prospective spouses) introduced to Nanjiani by his mother, possessed over-exaggerated South Asian accents and lacked personality, interests, or ambitions beyond getting married to a Pakistani-American man.

[Read Related: Kumail Nanjiani’s ‘The Big Sick’ is a Unique Love Story With Universal Truth]

Throughout the film, these women appeared to be waiting for Nanjiani to give them the time of day while he was busy living a full life and spending time with Emily. The particularly troublesome aspect of this negative portrayal was that it was perpetuated by a fellow South Asian. Aside from the likes of a handful of celebrities, such as Mindy Kaling and Priyanka Chopra, South Asian women are more or less invisible in the mainstream media. Nanjiani had an opportunity to showcase South Asian women as real, wholesome individuals, however, he instead opted to reduce them to stereotypes. Najiani glorified white women at the expense of brown women, subtly reinforcing the widespread harmful belief in white superiority.

Alongside this issue, I was equally frustrated by Nanjiani’s depiction of South Asian families as one-dimensional, obsessed with marriage, and distant, unlike his white girlfriend’s family which he presents as loving, open-minded and accepting. One of the film’s strongest themes is the juxtaposition of his lack of connection with his own family with his positive relationship with Emily’s family. Let me reiterate that if Nanjiani really did feel that he could connect better with Emily’s parents than with his own, he has every right to speak about that.

That being said, I am disappointed in the film’s message that white parents are somehow much “cooler,” easy-going, and fun to be around than South Asian parents. It is certainly true that many South Asian parents are more conservative and may not understand every aspect of their American-born children’s lives. However, this does not mean they love their children any less or that they would not welcome the opportunity to develop a stronger relationship with them. The notion that white parents as a whole are more loving and easy-going than South Asian parents is rooted in falsehood. Rather than examining the ways in which South Asian American children and their parents can connect, despite cultural differences, this film fixates on tired tropes about Brown families.

[Read Related: The Importance of Riz Ahmed’s Call for Representation]

I realize that this film is about Nanjiani’s personal experience and I respect him for speaking his truth. I also acknowledge that struggles related to identity, family, culture are valid and real for children of immigrants. I do believe, however, that he could have conveyed the same message without throwing South Asian women under the bus, depicting South Asian families in a negative light, and portraying white people (be it white women or white families), as somehow “cooler,” more evolved, and desirable. While I do consider it a victory for South Asians to have one of our own land a lead role in a mainstream American film, I also do not feel that this victory should come at the expense of the dignity of our community.

It is crucial that those of us who are awarded the opportunity to break glass ceilings do so with pride in our identities, and with the intention of pulling up other members of our community. With great power comes great responsibility, and it is imperative that more South Asian celebrities use their influence to break harmful stereotypes instead of perpetuating them. While South Asians absolutely should celebrate “The Big Sick” as a stepping stone, we must simultaneously recognize its blind spots as we advocate for more positive, holistic representations of people of color in the media.

Natasha Sharma is a recent graduate of the masters in social work program at Washington University’s Brown School. Her area of focus is issues affecting immigrant, refugee, and minority youth. Natasha hopes to eventually pursue a career in the field of ethnographic research, human rights, and community development. Alongside her social justice related efforts, Natasha does some fashion modeling. She hopes to use modeling as a platform to increase representation of women of color in the media.

Natasha Sharma is a recent graduate of the masters in social work program at Washington University’s Brown School. Her area of focus is issues affecting immigrant, refugee, and minority youth. Natasha hopes to eventually pursue a career in the field of ethnographic research, human rights, and community development. Alongside her social justice related efforts, Natasha does some fashion modeling. She hopes to use modeling as a platform to increase representation of women of color in the media.