Sitting in multiple history classes over my formative years, it never occurred to me that what I was reading about in the textbooks or seeing in the colored illustrations did not represent the full scope of our collective experiences through time. It wasn’t until a college literature class, during a lecture on E.M. Forster’s “A Passage to India,” that I realized how history was presented to me through the white male lens. My professor was a middle-aged white man and his perspective of British rule in India was quite different from mine. Suffice to say, I may have engaged in a heated debate with him over the cons of British rule, where he only saw pros. Since then, I have gained insight into the importance of books that present historical events or time periods through different perspectives.

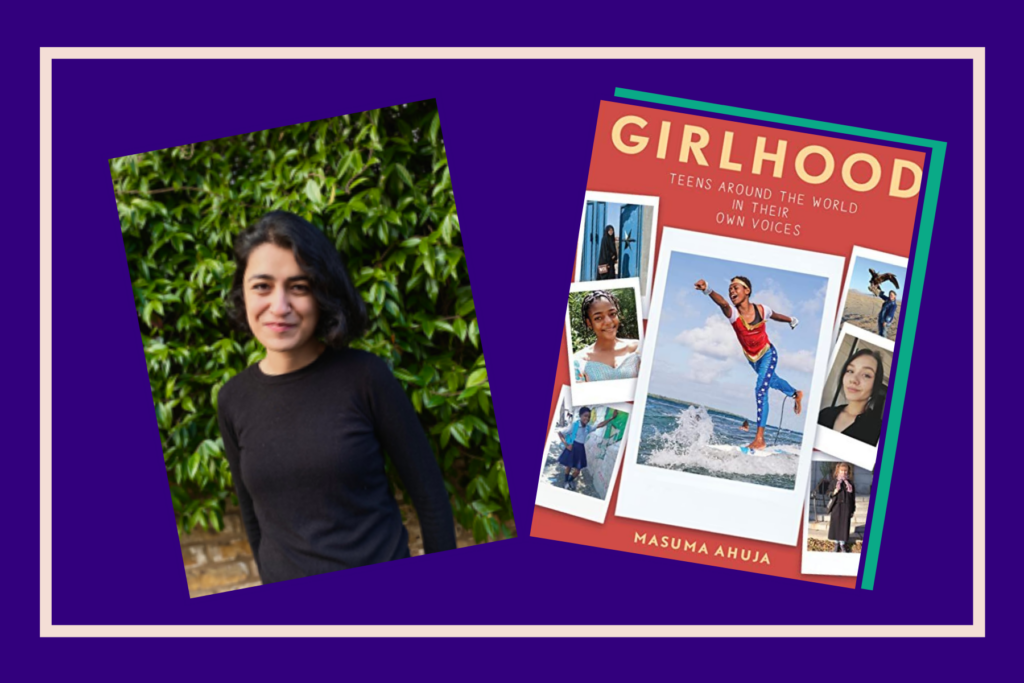

Masuma Ahuja’s book, “Girlhood: Teens Around the World In Their Own Voices,” is a perfect example of recording history through the lens of the actual teen girls living their authentic lives. Each diary entry, written between 2018 and 2019, is a look into the daily routines, worries, joys and innermost dreams of 30 young girls from twenty-seven countries around the world. Each girl is introduced with basic biographical data (name of the girl, country, age) with a beautiful, colored photograph of the teen, followed by a brief interview, a short summary of the country she is from and a few pages of her personal diary entries. There is no other middle voice filtering out the truth from these girls.

[Read Related: ‘Never Have I Ever’ Felt So Seen By a Mainstream TV Show]

Right from the first girl presented in the book, I was enthralled by every single teen. There is Alejandra, 17 years old and from Argentina. I chuckled when she wrote of how much she disliked her chemistry teacher and was elated to come to class one day to find a new teacher sitting behind the desk. I marveled at how brave Chanleakna, a 16-year-old from Cambodia, is for leaving her home and traveling to Australia all on her own for the opportunity for a better education. I smiled when I read 13-year-old Claudie’s diary entry about her passion for surfing. Surfing is the rainbow in her day. She lives in Pango Village, Vanuatu, where girls’ surfing plays a huge part in the effort to help empower women and girls in the region and chisel away at the dominantly patriarchal culture.

As I continued reading through the book, I compared and contrasted each girl’s story. Did the similarities or differences between them have to do with where the girl was from? Or how they were raised by their families? Or their socio-economic status? Surprisingly, the voices in these stories focused primarily on what home meant to them, how much they loved their families and how they envisioned using their resources or education to better their lives, as well as their families’ lives. The girls were more similar than different. They all had teen worries which transcended location, economic or social status, culture or religious upbringing. They spoke of friends, parents, extended family, siblings, tests in school and who they hoped to become in their future. Ahuja does an amazing job simplifying what is in the hearts and minds of teen girls throughout the world, normalizing the notion that our human experience is more closely associated with one another than many would lead you to believe.

[Read Related: Ambitious Girl: Meena Harris Changes the Narrative with Her New Children’s Book]

Masuma Ahuja based her book on the idea she originally chronicled in “The Lily,” which is a platform launched by The Washington Post for stories that are central to the everyday lives of millennial women. Ahuja’s 2018 series in “The Lily” was titled “Girlhood Around the World” and featured twelve girls from 10 different countries. The series was a success and propelled Ahuja to use her background as an award-winning journalist to extend her search for more teen girls around the world. Fortunately, for all of us, she was able to expand the series, which gave way to this empowering book.

Ahuja wanted to go beyond the statistics and dismal news reports focusing on the sexualization or victimization of girls in various regions. In the introduction of the book, Ahuja is passionate about wanting to know what the “ordinary, humdrum stuff that fills most people’s days but never makes their feeds” looks like. Ahuja understands what it means to be a translator of cultures as her own girlhood was split between India, the U.S. and the U.K. In the same vein, she recognizes herself in the voices of the girls in the book, as I am sure many of the girls or women who read this book will as well.

At the outset, Ahuja’s goal is for girls to see themselves in this book, to have a voice or identity which is reflected back to them. As so many have come to realize, voice matters, but more importantly, representation matters. The representation of girls in the telling of their stories depicts shared humanity, of different lives unfolding against different backgrounds but experiencing common emotions. I would recommend this book for readers of all ages, particularly young teenage girls interested in learning firsthand about their peers from different countries. The teen girls in this book welcome readers right into their homes and lives, giving the best travel guided tour of their world.

Follow Masuma Ahuja on IG @masumaahuja and buy “Girlhood: Teens Around the World In Their Own Voices!”