Migration is often the boldest, most heroic act of one’s life. It’s an accomplishment that you actually manage to pull off. But it’s also an identity we are somehow supposed to be ashamed of.

The partition of 1947 was one of the largest migrations in South Asian history. Territorial fights broke out over caste, religion and ancestral background. The notion of “belonging” to a state was in flux, it no longer had to do with your family surname or generational trade. Many different religions — Muslim, Hindus, and Sikhs — and regions — Sindhis, Punjabis, and Bengalis — all fled to other parts of India, Pakistan, or abroad. Violent territorial disputes occur to date. This intergenerational trauma of the displaced from 1947 is perpetuated to date – it’s a conversation that we need to acknowledge, talk about, and deconstruct.

That’s migration — a continual movement and displacement of peoples who are trying to reclaim their roots in a new space.

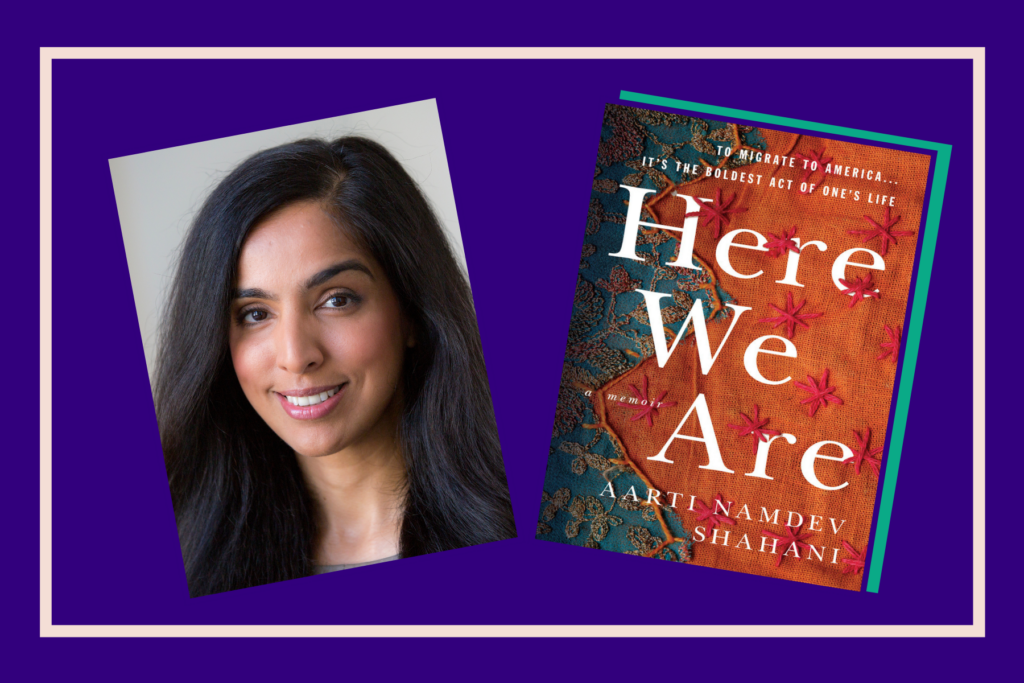

As I held award-winning NPR journalist Aarti Shahani’s memoir, “Here We Are,” in my hands, I felt that I was holding the story of truth – of the untold stories of thousands of immigrant families who have been slighted by the system, including my own. Shahani’s memoir is centered on her South Asian family that faced a grave immigration injustice in the late ’90s.

The story really begins during the 1947 partition, whereas a young boy, Namdev Shahani, Aarti’s father, flees India to go to Beirut and then Morocco. Eventually, he fell in love, married Aarti’s mother, and like many immigrants at the time, several reasons drew him to NYC such as it being the “land of opportunity.” Mr. Shahani migrated three times during his lifetime, finally setting his eyes on Flushing, Queens. Each time a family migrates, they are restarting their life, and not necessarily in the upper echelons of society. Like many, the Shahani family moved to Queens without much in their pockets, including any kind of immediate stable income.

Shahani’s words color the streets of Queens with moments from her life, from the inhospitable one-bedroom apartment that existed in a community building founded on a collectivist culture, to the opportunity-lined streets of the elite Manhattan private school she attended on scholarship. Like many first-generation children, Shahani and her siblings were navigating this new American world all while wrestling with traditional Indian immigrant thought in their home.

Typical Indian American stuff.

View this post on Instagram

Young Shahani was just reckoning with the ideas of privilege, power, and opportunity when her father and uncle, who were self-made businessmen selling electronics on west Broadway, are convicted for selling to members of an infamous Cali cartel.

The immigration policies set in 1996 (Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act and the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act) were created to more easily deport immigrants, especially those undocumented, for any criminal charge. In fact, the American fear of foreigners was so embedded in the law itself that deportation was a mandatory minimum. There were a countless number of families that immigrated during the 90s that lost their footing in the threshold of the Free World this way. Naturalization processes took decades, the police and investigative services were heavily involved, and many immigrants had their potential growth and future in America inherently stifled.

All because of the time and the laws in place.

[Read Related: 55 Years Later: A Comprehensive Look at the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965]

Shahani lost her uncle and his family to this clause, and she relentlessly fought and used her connections at her high school, Brearly, in order to find her father’s legal counsel so that history didn’t repeat itself. After she wrote to Judge Blumenfeld personally about the injustice in the courtroom, Shahani was labelled as the “Shahani family lawyer.”

Shahani took a year off from the University of Chicago to come back to Queens and be with her family prior to her father going to prison. During that time, she became active from a grassroots standpoint – speaking up for families that, like her own, were wrongfully accused, wrongfully labelled, and whose experiences were deliberately discounted.

I was beginning to see racial division as the central feature of America’s justice system.

Despite seeking legal help, her father’s case played out to be far more complicated because of a system that worked against rising immigrants. Upon visiting the prison, Shahani writes:

We weren’t taxpayers and voters worthy of respect. We were animals, just like our loved ones inside.

The Shahani family story gives a voice to those families that suffered at the hands of naturalization and anti-immigration laws that sought to snuff the opportunities out from hard-working, upright individuals. After completing the memoir, I got on the phone with Shahani to express my personal appreciation of representing many immigrant stories and to pick her brain about the definition of being American in today’s society.

The US is the ‘nation of immigrants.’ And there’s the reality of the lifelong campaign, it takes to become that. It’s not handed to you — you fight for it, and then you don’t wait for three years you fight for it for like 30 years.

There is a shame associated with fighting for where you “belong.” It was true back during the 1947 partition, and it rings true even now. Taken usually as a personal defeat, immigrant parents that struggle through years of a legal battle for naturalization are left with a detached sense of home as their thoughts are silenced — they try to live, try to forget, try to understand.

It’s much harder to get real people, living through real problems, to talk. We feel we can’t afford to be vulnerable. Our words can be twisted and turned against us. Yet it’s through speaking that I found concrete help.

Shahani admits that it was her schooling at Brearly that enabled her to speak for her family and other immigrant families.

It’s basically where I learned that girls can rule the world. And that’s the opposite message I got in my traditional immigrant home, where my mom pretty much thought that and she treated me like that was true but she wouldn’t say it. There’s no way my dad bought that.

Shahani learned about power and privilege, but also concrete skills such as writing effectively and public speaking. When Shahani started her activism, she found that:

Training was key, familiarity with the network was key.

When I asked Shahani about what made her begin writing her memoir, she said it was born from a combination of “existential need and historical moment.” The election in 2016 was a moment of reckoning for the entire nation. On top of that, Shahani internally looked at her personal story and knew that as a privileged person of color with a “megaphone” and strong platform, she owed it to herself and others to put her story out there.

At some point, something in life makes you take stock of the past. And that’s I think part of what I was working through in writing a book. Not everyone grapples with ‘where do I come from’ and ‘where do I want to go.’ Not everyone grapples with it by writing a memoir, but again I learned I’m a writer, so that’s how I basically gave myself like an epic homework assignment.

[Read Related: 7 Effective Ways to Help Fight for Immigrant Rights]

Eventually, Shahani went back to finish her schooling at the University of Chicago and asked herself what she wanted to accomplish professionally. Her experience using the power of the written word to advocate for her father certainly had a strong influence. Currently, Shahani uses her powerful prose and social skills as an NPR contributor. At first glance, this may seem disconnected from her past as a fiery grassroots activist dealing with immigration laws. In fact, Shahani has had a somewhat disparate yet continuous relationship with Judge Blumenfeld through the written word. Upon meeting several years after her father passed through the court, Judge Blumenfeld asked Shahani,

So what the hell are you doing with your life. He might have some notion that Shahani should go and become a defense lawyer and fight the good fight, because that’s what he knows. Now what I know is that I don’t feel like taking my talents as a storyteller and limiting them to courtroom briefs.

Shahani spoke about the current changing landscape for journalists, especially journalists from working-class backgrounds and journalists of color.

When we come into newsrooms, we’re told to stay away from the things that have personally affected us. That’s actually part of the media reckoning right now – what’s going on right now is the inherent racism and classism that governs editorial judgment. And so I would actually say, I gave myself permission to do [that]. A lot of journals frankly need to do that – to report out the facts of your own life and what it tells you about your country.

Shahani’s life is now primarily on the West Coast, where she reports on top technology companies in Silicon Valley. Anyone from the South Asian community would define her life as a “success.” It’s easy to spin a story around the individual. However, Shahani’s views strongly speak to the community, those around her, without whom she wouldn’t have been able to rise to her current accomplishments.

It’s very easy to make it and forget what it took to make it. It’s very easy to turn your success into some sort of self made narrative. That’s total garbage, that’s total fiction. But then you document what the journey actually was — the number of like aunties and teachers and supporters and allies that it took for one family to survive.

Weaved into those words are the loving emotions of a thoughtful, respectful, and hardworking first-generation daughter whose family was under attack from one of the most powerful governments in the world. Shahani’s journey to explore “Who really belongs in America?” left me angry, confused, and knowledgeable of how litigation and seemingly transient laws have a lasting, generational impact. I balanced these negative feelings with ones of hope, renewal, and a powerful understanding of love.

So many of our powerful experiences are shaped by our love for our family. When are you really putting yourself out there? When are you really giving all of yourself, testing your limits? It’s through your relationships: How deeply can I love? For me, loving meant being there.

Follow Aarti Shahani on Instagram and Twitter, and buy her memoir “Here We Are.” Shahani is excited to announce her upcoming show “The Art of Power.” Follow BrownGirlMagazine on Instagram for her upcoming book giveaway and Instagram Live!