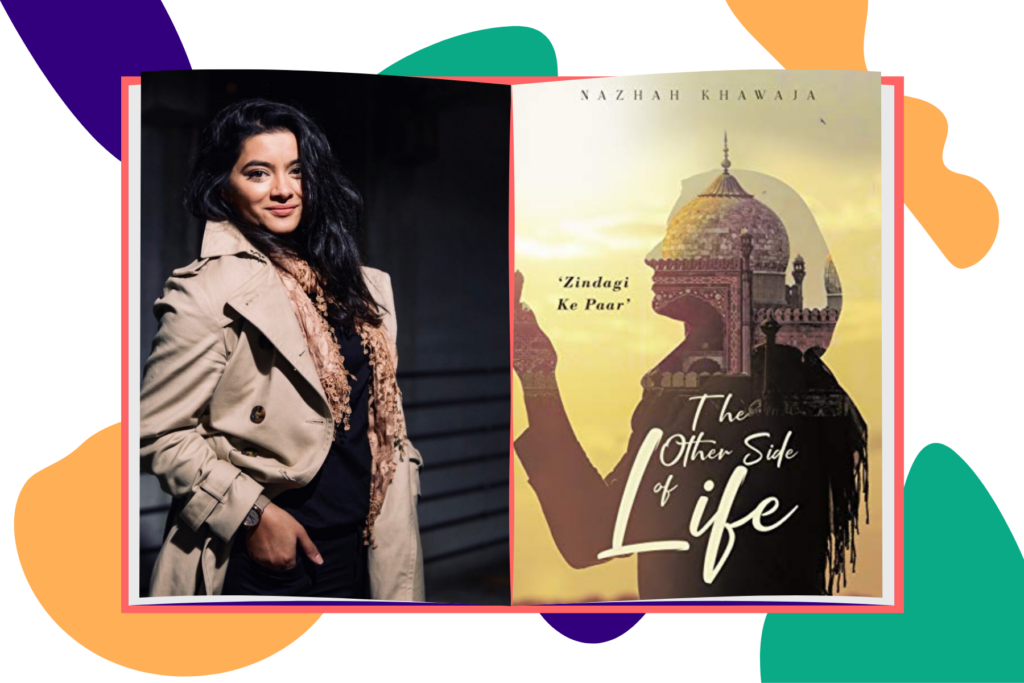

“The Other Side of Life” or Zindagi ka Paar, by Nazhah Khawaja, is a breathtaking and heartbreaking tale of the suffering that women face at the hands of a misogynistic and cruel world.

The story follows Farishteh, a young university student from an affluent family living in Lahore, Pakistan, with her violent father, stepmother, and siblings. The memory of her late mother, who died after her father refused her medical treatment, follows her through her days, as she tries to make sense of her place in the world. Her only support is her older brother, Ali, and Faizan, an orphaned friend of Ali whose parents died under mysterious circumstances. As time goes on, Farishteh senses that not all is as it seems with her father’s “real estate” business, and as she is kidnapped on her way home from university, she is forced to face a darker side of reality, where women are exploited in terrible ways. “The Other Side of Life” follows Farishteh as she comes to grips with the underground world of human trafficking, is thrust into terrible situations, and finds love and hope in unexpected places.

“The Other Side of Life” is a gracefully narrated read, reminiscent of Khaled Hosseini’s works such as “A Thousand Splendid Suns” and Etaf Rum’s “A Woman is No Man.” The reader is invited to explore the grim realities that face women in a world where they are considered less than men, simply for their gender; from being the targets of domestic abuse, refused access to basic services such as education and healthcare, to having their agency revoked in life’s big choices, and even being bought and sold for profit. A struggle as old as time itself, and a battle that is fought even now every day.

[Read Related: Author Interview: Resilience and Power in ‘Her Brave Journey’ by Swati Singh]

Nazhah is a multi-talented writer with a passion for expression who has written for many publications, performed poetry, and planned and hosted events in the Chicago area with the aim to empower women and create an environment of creative expression. “The Other Side of Life” was inspired by her time living in Pakistan, witnessing the treatment of women seen as inconsequential and experiencing it herself.

In a sense, “The Other Side of Life” follows a pattern familiar to those who have read books or watched movies that zero in on social issues in South Asian countries—the main character in a patriarchal environment living a limiting life, on the brink of being forced into marriage to an older, unknown man, refused the right to express her love to the similarly downtrodden boy she does love. It’s a slightly shorter read, with a fast-paced plotline, broken down into chapters that feature slower anecdotes and flashbacks. There are several descriptive scenes of sexual assault, so reader discretion is advised. A significant part of the story is set in a “high-end” brothel, where the sex slaves are given facials, yoga classes and unlimited lean meat at mealtimes, a far cry from the descriptions of sex trafficking hubs most people would have read about.

View this post on Instagram

[Read Related: Model Minority, Private Pain: South Asian Women and Domestic Violence]

One aspect which would have been interesting to explore would be a deeper insight into the other several women’s perspectives rather than just Farishteh’s. Although this is a tale of women’s inequality, it’s mostly Farishteh’s tale (with some focus on Farah, another girl who escaped death after a violent sexual assault), and it would have been great for readers to be able to see how sexism and patriarchal norms affect women across social statuses and norms; Anila, the stepmother, on the receiving end of abuse while watching her stepchildren suffer; Miss Samar, the Islamic Studies teacher; Goody, the brothel owner, Rani and Syeda, her assistants; the other girls forced to work at the brothel. Knowing more about the other women who played a part in this story could have added more depth and richness and given a better glimpse of how society consistently fails women.

You can purchase “The Other Side of Life” on Amazon and keep up with Nazhah on Instagram.